The Mystery of Dogtown | New England’s Most Famous Abandoned Settlement

With a past both sad and even sordid, Dogtown has drawn painters, writers, lovers of history, and seekers of solitude. What is its secret?

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanIn 1931, after more than three decades spent wandering this continent and Europe, the painter and poet Marsden Hartley arrived in Gloucester, Massachusetts, for the summer and fall. Nomadic by nature, Hartley was nonetheless exhausted when he settled into his guest house on Eastern Point. He spent several weeks sunning himself and recuperating, and then turned his attention to a lonely tract of boulder-strewn land in Cape Ann’s central uplands.

That place was Dogtown, known for its less-than-hospitable terrain and its history as a once-prosperous village turned rural ghetto. In what would eventually become a celebrated series of paintings, Hartley began rendering the Dogtown landscape. “A sense of eeriness pervades all the place,” Hartley would later write. “[It is] forsaken and majestically lovely, as if nature had at last formed one spot where she can live for herself alone.” Yet Hartley’s Dogtown work is imbued with spirit–of nature, yes, but also of the people who lived there once, and of the painter himself, who was born in Maine and who found in these paintings reconciliation with his roots. “What a distinguished spot my Dogtown is,” Hartley wrote in a letter to the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. “I could work in it for a lifetime.”

—-

There’s something ineffable about this 3,600-acre tract of juniper, bog, and granite — a quality that Hartley, whose powerful, primal paintings of the place include Rock Doxology, described as mystical. Still, to visit Dogtown can be to see one’s expectations confounded. It’s not a place that offers itself up easily. There are few signs, no storyboards, no tourist pamphlets. Paths end abruptly, sometimes in dense brush. Visitors in search of homogenized entertainment will be disappointed. Yet, in withholding its secrets while beckoning visitors again and again, perhaps Dogtown ensures that eventual discoveries will be that much more satisfying.

For all its difficulty, Dogtown has always had its devotees: history and nature lovers along with the artists, as well as people who go there for “the Dogtown feel,” as one walker near Whale’s Jaw, a two-part boulder formation, put it. Those numbers seem to be on the rise. At The Bookstore in downtown Gloucester, clerk and local poet Patrick Doud says that visitors frequently stop in looking for maps and materials, many of which play up the site as a ghost town. According to Suzanne Silveira, director of tourism for the city of Gloucester, Dogtown also draws geocachers, who, fittingly, search the woods for hidden objects using GPS tracking systems.

Photo Credit : Gray, Sara

Ted Tarr, a Rockport resident who leads tours of Dogtown, reports that he sees more people hiking there than ever before. Tarr should know: He’s been visiting Dogtown regularly for almost 60 years, having first become acquainted with it as a boy on Sunday botany walks. One tour Tarr led, in September 2006, drew nearly 60 people — after which he vowed not to do another unless he had help. “I couldn’t handle it,” he said. “Nobody could hear. Nobody could see.”

Despite the increase in visitors, it’s still possible to spend an entire morning in Dogtown without seeing another person. I began walking there a few years ago — a friend had told me about its mysterious atmosphere. The name, she said, originated from the packs of dogs living wild there after the village was deserted almost two centuries ago. That summer was a time of personal difficulty for me, and the thought of exploring a remote and mysterious place was appealing — not least because it afforded, at least temporarily, the chance to escape inner landscapes that were all too familiar.

That first visit, I expected antiquity — signs of abandoned domesticity. Instead there were gravel pits and an abundance of blueberries. The air smelled briny; beach roses added a high note. I’d been told to watch for cellar holes, but even with a map they proved difficult to find in the rocky woods. When I finally located one, I stepped inside and waited for a Dogtown mood. Nothing came. Shots from a nearby rifle range punctuated the quiet.

Soon it started to rain — big, hard drops that arrived without wind or other warning. Lightning flashed; wood cracked. I took shelter beneath a boulder, huge and angled in such a way that I could only hope it wouldn’t roll. After half an hour, the shower let up. The spot where my back had touched the rock was dry, the surface oddly flat. As it grew lighter I could see block letters carved into the granite: “If work stops values decay.”

I picked up my bag to head back. The woods were rain-slicked now, and heavy. Nothing looked familiar. I made several turns onto ever-smaller trails that crisscrossed and looped, before realizing I was lost. It began to rain again. Eventually I made my way out — not to where I’d entered, but to a place that let me loop the perimeter and locate my truck. Hours had passed. I was bug-bitten and soaked. I was also determined to come again — next time with a better map and a clearer sense, at least in physical terms, of what it was I hoped to find.

—-

Dogtown maps were easy to obtain, it turned out, but reliable information less so. Ascertaining what happened there centuries ago is tricky. Some folks want to embellish it, others to deny it — the accounts therefore larger or smaller than the truth. Yet certain facts converge: Homesteaders first put down roots in what was then known as the Commons Settlement during the mid-1600s. Although the village lacked tillable land, it drew people because its elevated location made it less vulnerable to attack. The place had plenty of pastureland, too, plus a brook that powered a sawmill. In 1719, a general land distribution for men expanded the population; by the mid-1700s, as many as 100 families lived and worked in the Commons area.

Life there was stable until after the Revolutionary War, when a revival of fishing triggered a shift back toward Gloucester Harbor. The area fell on hard times after the demise of the original settlement: “Dogtown became an aberration, an embarrassment,” wrote Thomas Dresser in Dogtown: A Village Lost in Time. He described one inhabitant, Tammy Younger, as “queen of the witches,” who so intimidated passersby that they left her tithes of fish and corn. By 1828 the village was all but deserted. The last resident, a freed slave named Cornelius Finson, was found with his feet frozen and taken to the poorhouse in the winter of 1830.

With an eye out for cellars and rock walls and signs of Finson or other ghosts, I continued to walk in Dogtown, and I kept getting lost. My father, who had taught my sister and me how to navigate the woods behind our house when we were growing up, took exception to this. Slow down, he said. Retrace your steps the moment you’re not sure where you are. I knew to carry a compass and to watch the sun on my way in, but in Dogtown, it seemed, the sun reoriented itself at will.

—-

On Cape Ann, what did or might have happened in Dogtown has long been part of local lore. “The walled ruins of Dogtown draw the curious and speculator,” wrote historian Charles Mann in 1896. “Why did more than one hundred families exile themselves from the life of the villages so near them, and dwell in loneliness and often in poverty, in this barren and secluded spot?”

That same question was at the heart of a Sunday morning walk taken recently by a local family to celebrate the birthday of its matriarch. In addition to Barbara Stewart, who was turning 80, three of her daughters, two sons-in-law, and four grandchildren gathered in a parking lot off Cherry Street in Gloucester. Directing the two-hour tour were Seania McCarthy and Dee McManus, who offer guided hikes in Dogtown. Sunlight filtered through the trees; McManus’s dog, Cooper, led the way.

“I’m so glad we’re finally doing this,” said Stewart, beginning the easy ascent on a paved road that soon gave way to gravel. A few minutes down Dogtown Road, McCarthy directed the family to pause, indicating a heap of rocks in the woods — an ancient house site. “Number 15; this one belonged to Easter Carter,” she said. McCarthy described Carter’s two-story house, grand by Dogtown standards, and Carter herself as a spinster who nursed others. She also alluded to an upstairs tenant: a cross-dressing stonemason, a former slave named Old Ruth, a.k.a. John Woodman.

“It’s all interesting,” said Stewart, leaning on her walking stick to listen to the story of Carter’s life and–at cellar hole #17–that of her neighbor, Dorcas Foster, who allegedly arrived in Dogtown as a young girl after her father was killed in the Revolutionary War.

After about 30 minutes, the group arrived in Dogtown Square, a humble place even as ancient squares go. The cellar hole from Granny Day’s schoolhouse and a sheep-swallowing swamp lay to the west, Wharf Road to the north. McManus and McCarthy led everyone south, into the terminal moraine that is Dogtown’s most prominent topographical feature. This area is a product of the Ice Age, when melting glaciers dropped their rocks, some as large as houses, plus other “erratics” borne from far away.

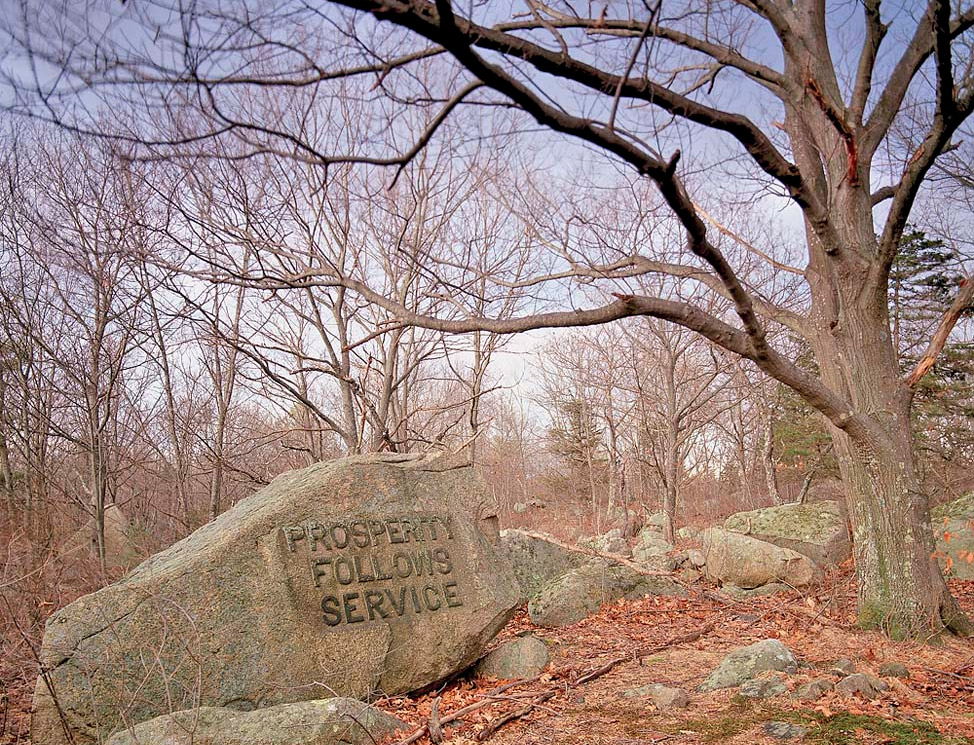

It’s also the site of the Babson Boulder Trail, named for financier Roger Babson. A Gloucester native who founded three colleges, Babson purchased much of Dogtown’s land and turned the place into something of a classroom by commissioning quarry workers to carve inspirational phrases into 24 of the most imposing boulders here. Of all the efforts to develop Dogtown — including a 1944 plan for an airport in the Whale’s Jaw area, a 1967 Department of Defense consideration of Briar Swamp as a radar installation site, a 1970s proposal for an Old Sturbridge Village-style attraction, and, most recently, an attempt to locate a windmill farm here — Babson’s plan was the only one to materialize.

Babson’s 1930s project didn’t meet with universal approval, though. Reading from a notebook, McCarthy quoted Babson: “My family says that I am defacing the boulders and disgracing the family with these inscriptions, but the work gives me a lot of satisfaction, fresh air, exercise, and sunshine. I am really trying to write a simple book with words carved in stone instead of printed paper.”

McCarthy pointed out several of the inscribed boulders, many of which were not immediately visible in the dense woods: Be on Time, Study, Initiative, Keep Out of Debt. “Definitely New England values,” said one of Stewart’s sons-in-law. “Puritan,” said another.

Two of the Stewart grandchildren posed for a photograph beside Use Your Head, and — after a non-Puritan-like pause for chocolate-chip cookies and snake viewing at Spiritual Power — the whole group assembled for a picture in front of Kindness.

It was nearly noon, time to turn back. On the way, McCarthy pointed out the place where James Merry, a fisherman and railroad worker also known as “the Dogtown matador,” died after being gored by a bull. Three rocks here bore carvings: the first, Jas. Merry Died Sept. 18 1892; the second, First Attacked; the third, a Babson inscription, Never Try Never Win. “Maybe he was referring to the bull,” someone said.

Turning back onto the trail, Barbara Stewart headed in the wrong direction. “This way, Mom,” said one of her daughters. Stewart swung around: “I’ll bet it’s easy to get turned around in here.” McManus said that it was, that it was easier to find your way in late fall and winter, when the leaves were down. She mentioned, too, that it was beautiful. Stewart paused, took in a sun-dappled boulder to the left and an unexplored path to the right. “We should come back,” she said.

I understood what she meant. My own hikes in Dogtown continued through a summer and fall, on Halloween and during hunting season, when I saw hunters but no deer. In the spring, perennials bloomed. I grew to love the place — I found it finite and increasingly navigable. There was also disappointment. I went in search of Whale’s Jaw to find it broken in half; succeeded in locating only 20 cellar holes, when 40 were listed. Even so, through good walks and bad, I felt connected to the place. In mapping its terrain, I figured out some things about myself.

—-

After the summer of 1931, Marsden Hartley returned to Dogtown one last time, in 1934. But, like a fickle lover, Dogtown withheld from him its previous charms. Or maybe it was Hartley who had changed. Distracted by financial worries and the looming war, he could no longer find the magic of the place. And there was something else: Hartley, in his time away from Dogtown, had embellished it in his mind. “I had lived it over so intensely in my imagination,” he wrote, “that the thing looked like nothing when I got here.”

Maybe this, then, is one secret of the place: Go emptied of expectation. Plan nothing, set linearity aside, and let Dogtown offer what it will.

—

Finding Dogtown

In Massachusetts, take Route 128 north to Grant Circle, a traffic rotary, in Gloucester, and turn north on Route 127 (Washington Street), toward Annisquam. In one mile, take a right on Reynaud Street and follow it to the end. Bear left on Cherry Street and turn almost immediately into the entrance to Dogtown, up a steep drive on the right. Public parking is available on both sides of Dogtown Road before the gates. For guided-tour information and reservations, contact Seania McCarthy and Dee McCanus at 978-546-8122, walkthewords.com.

Since I am an artist, I was a fan of Marsden Hartley’s art. I enjoyed this article very much. Thank you.

How about Dudleytown in northwest CT? This is a fascinating story but no one will tell you exactly where it was. it is a forbidden place.

This is definitely one of the top options trading posts I’ve examined in years.