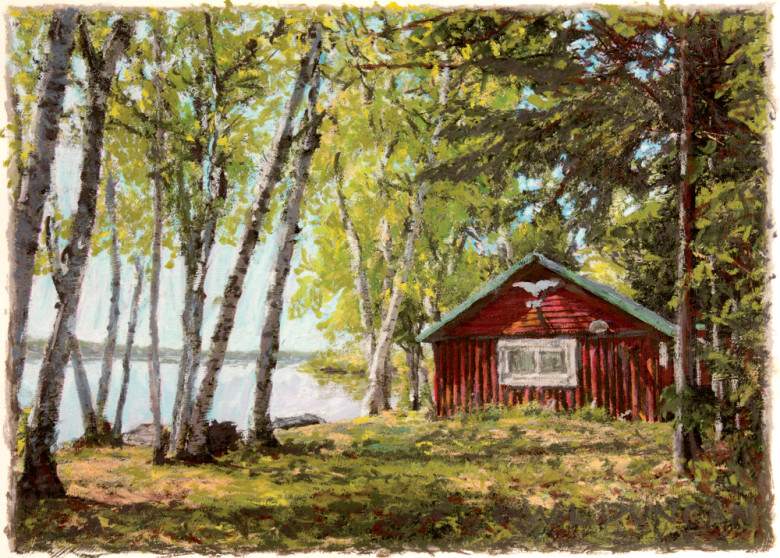

A Place to Get Away | Maine Summer Camp

A summer camp is not about place. It’s about time, and time slows down at a Maine summer camp.

Built in the 1950s and left largely unaltered, the author’s camp preserves the simplicity and ease of those pre-high-tech days.

Photo Credit : William Lloyd DuncanMy wife and I own a Toastmaster Automatic Popup Model 1B14, which was made by the McGraw Electric Company in the late 1940s or early 1950s. We got it with the camp we bought in eastern Maine nearly two decades ago. It makes toast. Perfectly. Every time. You put in two pieces of bread. You press the Bakelite handle down. The toast pops up less than three minutes later, and the bread is crisply and evenly browned on both sides. Apparently it’s been doing this for longer than I’ve been alive. This strikes me as a small miracle, given that every new toaster I’ve ever bought has been flawed in one or more ways: striated toasting, requirement of repeated down-clicks, passive-aggressive rebellion against the repeated down-clicks, far too much standing around and fingertip drumming. And still these often make toast that somehow fails to match the replicable standard of being crispy on the outside and pliable on the inside. Also, the new toasters that I buy invariably stop working after a few years, and require replacement. I understand we are in a golden age of technology, yet it appears we’ve lost the ability to produce machines that can consistently make toast.

Photo Credit : William Lloyd Duncan

There are other things at our camp that impress me similarly—our place is essentially a museum of Darwinian technology. Anything that failed was discarded, and items that have proven themselves over the past half century remain. (Also, a camp year is approximately four months, so things wear out less rapidly.) Our electric range, I’m guessing, dates to the late 1950s, the outboard engine to the early 1970s, and the avocado-green rotary-dial phone in the kitchen is clearly mid-1970s. All work just fine. The cherry-red living room carpet was likely installed in the 1960s, yet it has not faded where the sun hits it. The carpet probably should be in the Smithsonian, an artifact of when America knew how to make synthetics that can last forever yet still offer comfort when the shirtless choose to repose on the floor on a warm afternoon.

We bought our camp in Maine’s Washington County for many of the reasons people buy camps. That is, to have a place to get away when the weather is warm, a place so quiet you can hear moose crashing through the underbrush on the ridge above, or a squally wind rising in the pines a mile away down the lake. When we bought it, it seemed a matter of simple geography, of finding a place with less pavement than soil, with more quadrupeds than bipeds.

But after 20 summers, I’ve come to realize that the essence of a camp is more complicated than that. A summer camp is not about place. It’s about time.

My camp clock starts each summer with a quick survey of our property. Even before unlocking the door, I walk once round the house, figuratively sniffing, like a dog sussing out an unfamiliar place. Our camp is surrounded by a dozen or so towering hemlocks and white pines, and I first check for winter casualties. Once inside, I insert a brick-size fuse that allows the electricity to flow again. Then I literally sniff. There’s a spot between the coat closet and the fuse box where mice often host what appears to be their own annual Coachella; if I can smell it from four or more feet away, I know to put nest extrication and space sterilization on the list of chores for that afternoon. I also inspect the interior to see if our winter bandit has made off with anything substantial—usually not, although this bandit is crafty and knows to take things that might not be missed right away. One year it was a braided carpet. Another year it was a tent. And one year it was a half-dozen bandanas in my sock drawer. Who steals a half-dozen bandanas? I assume it’s someone who doesn’t want to make the 45-minute drive to the nearest Walmart.

Afterward, I walk the trail through the pines and down to the water to see what the ice has moved around. Usually, the alder-covered point and the small pebbly beach next to it have shifted almost imperceptibly. Ice is slow, but it’s steady. It took me almost a decade to even notice that the land was creeping away. But now the fact that the point shortens and the sand migrates each by a few inches every winter strikes me as a dramatic change. I know there’s nothing that can be done about it, and it seems that eventually—although not in my lifetime—we will no longer have a beach, and my neighbor will. The movement of the sand puts me in mind of sand clocks.

Our camp, like so many on Maine lakes, was originally built thanks to a society-wide realignment of people’s relationship with time. For centuries, only the wealthy had the capacity to cease working for extended periods, often in the summer, when the weather was agreeable. Everyone else worked nonstop to raise livestock and grow produce to survive (especially in the summer), or made handcrafted objects to be sold, affording them little luxury of time. “Before the 1830s, everything was made individually,” says Steve Pinkham, who has been researching Maine sporting camps for years. “With the industrial revolution came mass-produced stuff, and it also created a middle class.”

Photo Credit : William Lloyd Duncan

That middle class found itself with some unaccustomed free time and a bit of cash. What to do with it? The sporting life was in full flower by the end of the 19th century—former Civil War soldiers had returned to civilian life, and many brought with them outdoor skills and a fondness for activities like baseball, boxing, horse racing, camping, and fishing. America set off into the woods en masse, including the Maine woods, which were convenient by train and steamship to many eastern seaboard cities.

The rise of the sporting life had a coconspirator: the improvement of the window screen. The woven wire industry had been around since the early 19th century, but rust was an endemic problem, and not until galvanized wire became widespread around 1900 did practical, inexpensive window screens emerge. At the same time, there arose an increased awareness of mosquitoes serving as vectors of diseases—Walter Reed made the connection with yellow fever in 1901—and suddenly screens were everywhere. Screens were “no longer a luxury but a necessity of modern life,” insisted Sears Roebuck in its ads. They meant one could spend time relaxing rather than attending an involuntary festival of swatting.

Sporting camps were built for these newly affluent sportsmen, and many later bought lakefront land and built their own places. Those who already lived here went deeper into the woods. In the more remote parts of Maine, mill workers often acquired their own camps—it was part of the social contract. They worked hard making paper and two-by-fours; in return, they received not only a decent salary and vacations but also access to waterfront property on company timberlands. It was common practice for these workers to pay a lease fee of about $50 a year for 50 feet of lakefront, and in exchange they were allowed to pitch a tent or build a lean-to so they could spend their weekends fishing and hunting.

As savings allowed, they’d boat in some lumber and nails to build a basic cabin, and then they’d bring their family, and eventually their kids would grow up and move away to Connecticut. But the kids would come back in summer, and with their improved incomes they might build something bigger and more ambitious. Then the next generation—the grandkids who grew up in Connecticut and then moved to New York City—would lose interest in the Maine woods and sell the camp after it was passed down to them. And so a retired insurance agent from Boston who loved to fish could buy it, and the intergenerational process would begin anew.

As best I can tell, we are the third owners of our camp, which dates back to the early 1950s. The man who built it was evidently a paper mill executive; when he took up hammer and nail the only access was by boat. He later sold it to a nearby pharmacist, who spent nearly 40 summers with his family here, along the way adding some small buildings and widening a logging road to allow access by car.

We bought the place fully furnished, down to sheets and towels, from the pharmacist in 1998, after hearing through a mutual friend that he was thinking of selling. The day we purchased it we went by his house in Calais and sat in his living room. We gave him a down payment, and we agreed on an interest rate and monthly payment. (We never once visited a lawyer or a bank.) He then gave us keys and a brown paper bag with a set of antique nature identification guides, two rolls of toilet paper, and a new steel brush for cleaning the barbecue grill. He apologized for having forgotten to clean the grill when he was last there.

Camp is an elusive noun, and subject to many gradations with regional variations. Essentially, it’s a subset of summer home and a sibling to cottage, another slack term that resists efforts to tone up. In Maine, camp usually means a place that’s not inhabited year-round and tends to be inland. (Cottages tend to be coastal, although not always.) A camp can be a fishing camp or a hunting camp or just a camp, although none of these should be confused with children’s summer camps, which proliferated in the early 20th century and in the Internet age survive only through nostalgia and institutional momentum.

The vague vocabulary can be confusing to outsiders, who look at real estate ads and see no difference between a “vacation home,” a “camp,” a “cottage,” or, for that matter, a “house.” (Confusing matters more, what would be called a camp in Maine is often called a cottage in Canada.)

According to The Oxford English Dictionary, the term cottage has been used in North America since at least the 1880s to describe “a summer residence (often on a large and sumptuous scale) at a watering-place or a health or pleasure resort”; its first recognized use was in reference to resorts in Bar Harbor. In her book Country Cottages: A Cultural History, Karen Sayer, an Englishwoman, defined a cottage as being of “small size,” with an “organic unevenness shaped by time and weather” and an “unpretentious interior.” That definition works quite well for a camp, although perhaps a more encompassing definition would be this: A camp is a small, nonpolluting manufactory at a remove from others, where, with the application of time, memories are crafted.

After I return each summer, I spend about two days sweeping up mouse pellets and tacking screens back into place. It’s part of a seasonal cadence, an annual ritual, but at a certain point, usually after about a week, the sense of occupying a calendar composed of months fades, and I start to notice again the daily, short-cycle rhythms of summer life.

The ultimate camp sound is that of a slightly rusty screen door being stretched as someone in a camp down the lake heads outside, and then slamming shut with a brief thunderclap that, two or three seconds later, echoes across the lake.

Camp owners or renters often come for a week at a time around our cove, generally arriving on a weekend afternoon. That’s when I hear the distant sounds of tires slowing on gravel, and doors slamming—pompf! pompf! pompf!—and then the shouts of excitable children, soon followed by the repeated shrieks that punctuate leaps into a cold lake. This excitability slackens by the second day and becomes a more measured performance, with only the occasional glissando. By the next-to-last day you’re hardly aware anyone is around—I like to believe a concerted effort is under way to complete a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle before departure, although maybe they’re just napping. Then comes the final day, and new door-slamming rhythms signal imminent departure. Soon will come the distant hum of a vacuum cleaner, followed by shouted riffs on the theme of “I said now!”

Nobody wants to leave. But finally the last car door slams, more hesitantly now. Arrival slams are like exclamation points, where departure slams are like closing parentheses. Then the fading sound of tires on gravel. Then silence, until the next arrival.

Of course, I have my own personal ebb and flow throughout the summer. I spend much of my time here alone—until my wife gets away from her job and arrives for three or four weeks and we load tents and sleeping bags into the canoe and head up the lake to camp out on islands and forested points.

Friends steadily filter in throughout the summer, with regular, longtime visitors arriving on “their weeks,” and newcomers fitting in between. I always welcome this, particularly when I can entice my nieces and nephews to come north to visit. Youth is pleasingly allergic to the complacency of camp life, and prefers at least the illusion of hazard and escapade. So we explore mossy ledges, and always detour by a large glacial erratic in the lake that’s ideal for leaping and diving into clear water. Each time a niece now asks me, “Aren’t there any higher rocks?” I recall the terror in their faces when they refused to jump off when younger.

We also have two couples, friends from college, who have been coming with their respective pairs of kids every summer for more than a dozen years. So the kids have grown from 6-year-olds into hulking teens who play board games until late, sleep until noon, and then spend the day consuming the entirety of the refrigerator.

All eight were visiting three summers ago when a powerful nor’easter blew in late at night. A large maple tree fell across the road, blocking us in, and our water started to fail after the winds churned up hemlock needles, which got into the intake pipe. The kitchen sink and the toilet failed, one after the other. Then the power went out.

It resulted in one of the more memorable visits, mostly in a good way. Like generations before us, we found that when chores have purpose and meaning, teens are good for hauling water and firewood; the sullen grousing fades. The rains passed by, and we moved the kitchen outdoors for a couple of days—cooking over open fires, which also served to heat water for cleaning dishes. In the evening, we played board games by candlelight.

Upon leaving, one of the parents commented that most summers we went out looking for adventure. That summer, the adventure came to us.

Our town, which has a year-round population well into the low three digits, got a grant and installed an 80-foot tower a few years back in order to bring in high-speed Internet. The town felt this was essential to prevent the population from dipping into the low two digits. Many residents installed pizza box–size receivers that allowed the Internet to come into their homes in torrents. We haven’t been able to do this at our place; there’s a hill between our camp and the tower, so the Internet company tells us that we’re in a shadow that blocks us from accessing the cloud. Also, there are the trees—the technician who came out to investigate wrote on his form “1,000 feet of trees” as another reason for our being an involuntary informational hermitage. I used to have positive associations about summer and clouds and shadows and trees, but now our relationship is more complicated.

In truth, I’m a bit relieved we don’t have Internet access at our place. The Internet is to time what a vending machine is to nutrition: always there, always tempting, always full of empty calories. I actually work from our camp most of the summer and need to be periodically connected to the world so editors can yell at me and send me emails in all caps. The avocado-green rotary-dial phone is helpful, as cell service here is also nonexistent—except on days of high cloud cover and low atmospheric pressure and if the phone is propped up in the second window from the front, near the dining room table.

To collect email, I usually walk three-quarters of a mile through the woods into town, where I can tap into the Wi-Fi aquifer. I used to do this at the post office, and it brought me a small amount of joy to tell people I had to walk to the post office to collect my email. But the post office closed down three years ago, and our postmistress was replaced with roadside high-density mail clusters, steel boxes that bring to mind Soviet-era housing developments. Now I often get email at the general store, which also has Wi-Fi and where I can eat potato chips as I respond to shouting editors.

So in lieu of frantically clicking around Facebook and Twitter, I read books in the summer. Around the first of each year, back in my winter stomping grounds, I’ll start to fill a milk crate with books. Then I spend summer mornings and evenings on the screened-in porch, reading. It takes a while to get back into that rhythm—I’m not ashamed to admit that more than once I put my finger on a word and hoped for a window to pop up and define it. Though reading in print feels a little retro at first, I find I can slip into the habit easily. Canoeing rapids is fun, but so is paddling across a wide and placid lake, slowly, with measured strokes, with plenty of time to enjoy the view.

Closing up for the season is much faster than opening up. I nail up the shutters and drain the pipes and hide shiny things that might catch the eye of our winter bandit. And if there’s bread left, I’ll scatter it in the yard for the birds and squirrels. I’ll save one slice to make a last piece of toast.

And then I’ll get into my car and pull out without looking back, because to do so is too sad. I leave the camp to the woods—to the mice and squirrels and the winter bandit and the towering trees that in the snows may come crashing down expensively.

And so I plunge back into the nattering, quickening torrent of everyday life. Until next year.