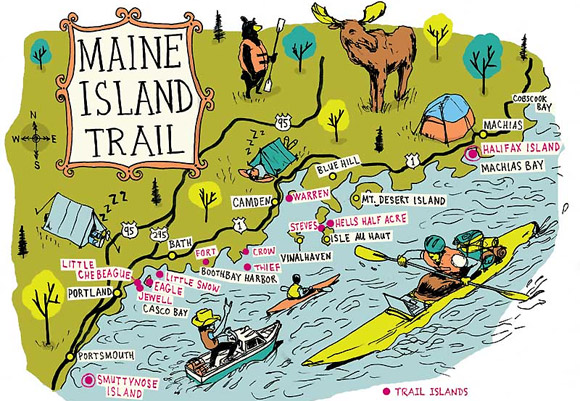

Paddling the Maine Island Trail

Ever wondered what it’s like to live cheaply for a month and to paddle 325 miles in a kayak? Try the Maine Island Trail. My plan on the first day of August 1989 was to paddle a fiberglass kayak some 325 miles northeastward along the Maine coast to Machias, camping on islands along the way, […]

Ever wondered what it’s like to live cheaply for a month and to paddle 325 miles in a kayak? Try the Maine Island Trail.

My plan on the first day of August 1989 was to paddle a fiberglass kayak some 325 miles northeastward along the Maine coast to Machias, camping on islands along the way, living a sort of Robinson Crusoe existence for a month. The problem: Prior to that moment, I’d never actually paddled a loaded kayak, never paddled through breaking surf, never paddled in fog.

Photo Credit : Byers, Michael

Some of the biggest adventures are born of small ideas. The small idea behind this journey–to live really cheaply for a month–involved more of a push than a pull. The agreement with my landlord was that I’d relinquish the house on Peaks Island for all of August. I was reasonably young, had little money and fewer obligations, and I’d heard about the recently created Maine Island Trail, a network of three dozen or so islands no more than a day’s paddle apart, where anyone could camp for free. Why not paddle the whole thing?

So I bought a used kayak and paddled around Peaks twice to gain expertise; then a friend taught me to identify edible island plants. Most of them, as I recall, tasted like iodine. Immediately afterward, I bought a boatload, quite literally, of pasta. Over the course of the next month I discovered that rotini boiled in seawater with freshly gathered mussels and tossed with a little wild mustard and a lot of black pepper was actually pretty good.

Photo Credit : Welsh, Dennis

My route to the first night’s campsite was neither the most efficient nor the most direct. At least, I don’t believe it was; I’m not sure exactly how I got there. But I landed some hours later on a foggy gravel beach at an island a few miles offshore, then immediately dug out a book I’d recently bought (and hadn’t read) on kayak navigation. I began what would be the first of many hands-on lessons that month.

The fledgling Maine Island Trail itself, as it happened, was also born of a simple idea that quickly grew more sophisticated. In 1987, the nonprofit Island Institute undertook a survey of Maine’s state-owned islands with an eye toward their potential for recreation. There were about 1,300 of them in all–many just uninteresting bits of surf-washed ledge. “But in the course of the survey we came across 30-odd that had tremendous recreational potential,” recalls Dave Getchell Sr., then an editor with the institute’s Island Journal. “And it occurred to me that if we set up a water trail instead of a land trail, people could cruise along the coast and have a place to stay at night.”

Getchell wrote an article outlining the idea of a water trail. He was soon awash in enthusiastic responses. The following year the Maine Island Trail Association was established as a program of the Island Institute.

The trail would be open to both paddlers and motorboaters–anyone adept at pulling up on a rocky shore or mooring in tricky conditions. The idea was embraced not only by these recreational boaters–all of whom seemed to have an inordinate love of islands–but also, perhaps surprisingly, by individuals who owned private islands. Many were happy to open their properties to camping, in exchange for which they’d get free stewardship services; volunteers would keep an eye on the islands through the summer, clean up trash, and keep pathways clear.

So a handful of private islands were added to the public islands in the network. The first guidebook–a few dozen photocopied pages stuck in a looseleaf notebook–served as both passport and guide and was mailed to the first round of members. I still have my well-used copy.

My month-long journey involved not only honing camping and kayaking skills but getting an advanced education about the Maine coast as well. Among my first lessons: The Maine coast wasn’t the wilderness I’d thought it was. No matter how remote an island, come dawn I’d be awakened by the throaty growl of a lobster boat hauling traps, sometimes just a few dozen yards from my tent. Also, I learned that lobstermen like country music, played loud–in particular, Ricky Skaggs. Some mornings, awakening from a deep sleep, I was convinced I’d accidentally pitched my tent at a Midwestern truck stop. I grew to like the social aspect of the trip. The lobstermen were cordial if not garrulous, happy to exchange waves as I sipped my morning tea on a rock. (I learned later that they privately refer to kayaks as “speed bumps.”) What’s more, I was rarely more than a couple of hours from a lively harbor, and so every few days I’d veer landward for a lobster roll and a cold beer, then fill up a slew of empty quart bottles with fresh water. (Only one island on the trail had drinkable water.) Then after lunch, I’d set off back out into the archipelago as the lowering sun turned the world around me into a vast Eric Hopkins painting.

Photo Credit : Welsh, Dennis

Afternoons on the islands were my favorite times; most of the working boats had returned to their home harbors, and peace and quiet had settled offshore. Often a woolly cloak of gray fog would roll in, making an island two miles out feel instantly like 200 miles away. Evenings were monkish and solitary. Sea kayaking was still pretty much in its infancy two decades ago–during the entire month of August, I crossed paths with only three other kayakers–and I spent many nights engaged in a favorite pastime: lying in the grass, looking at the stars, and thinking how stupid people were not to all be camping on Maine’s islands.

Well, it turned out people weren’t all that stupid. Many did start to come out to the islands in subsequent years, and in droves, causing some worries and aggravation. Sea kayaking took off as a sport nationally in the early 1990s, and suddenly every third car on the Maine Turnpike looked like a mobile missile launcher. The Maine Island Trail Association–which had become an independent nonprofit after a split from the Island Institute–took the brunt of the blame, with some lovers of the coast blaming the group for promoting the islands and encouraging overuse.

“Over time there’s been a lot of hand wringing, in part because people thought there was a correlation” between the national surge in sea kayaking and MITA’s founding, says Doug Welch, MITA’s current executive director. He notes that island overuse is a legitimate concern, but adds that the group’s goal has always been to get ahead of the curve, not only by channeling visitors to islands that could best handle recreational traffic, but also by instilling a strong conservation ethic among visitors.

Photo Credit : Welsh, Dennis

Membership in the organization has held pretty steady in recent years: about 3,600 dues-paying members. And although, according to Welch, day use is up, particularly in the more populated areas such as Casco Bay, island camping seems to be on the decline–again mirroring a national trend, this time away from backcountry camping.

Spreading a low-impact ethic, Welch says, is among MITA’s chief accomplishments over the past 20 years. MITA is now really more of a conservation group with a recreational element, rather than the other way around. Most of the islands were once littered with plastic debris that had washed ashore and had been blown into the interior by winter winds. From the beginning, MITA has sent out volunteers in empty skiffs, which return hours later mounded with polystyrene rope and plastic bottles. Although new harvests of plastic arrive on the tides every day, the islands are cleaner now than they have been in decades.

“The leave-no-trace ethic has sunk in for the average visitor,” Welch says. “It’s the ‘broken window’ theory: If you come upon a place that’s trashed, you won’t think twice about littering. But if you come upon a place that’s totally pristine, it takes a pretty self-centered person to leave something behind.”

The Maine Island Trail is today recognized as the first of the modern water trails–although water routes have, of course, existed on this continent since shortly after the Bering land bridge was crossed–and dozens of others have cropped up around the nation since. But MITA remains a singular organization. Welch says that people aspiring to launch water trails in their own regions often ask to see the contracts spelling out terms between private-island owners and the group. But there isn’t one: “We’ve managed to do this all along without anything more than a handshake. Other trails find it hard to believe that there’s no paperwork or legal agreement. It’s uniquely Maine, and I can’t see it working in other states.”

Late last summer I set out for a few days of paddling along the eastern end of the trail, heading out from near Machias to Halifax Island, the last island I’d camped on in 1989. The region is largely overlooked by paddlers: It’s too far from any town, too foggy, too swept by intimidating tides.

Photo Credit : Welsh, Dennis

Halifax was as lovely as I remembered it: a mostly treeless knob of about 60 acres, with high, rocky bluffs on the southwest corner. It had been hammered a couple of weeks earlier by waves from Hurricane Bill passing miles offshore: the grasses flattened, and bright-red rose hips clinging to bushes turned brown from saltwater. Halifax was privately owned when I camped here two decades ago. It’s now owned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which has posted it with signs banning access to the delicate bogs of the interior, where I’d once filled empty water bottles with blueberries and raspberries. (Camping on Halifax requires both MITA membership and prior permission from the USFWS.) Other than that, the place hasn’t changed.

The context has altered somewhat, though. Halifax is no longer the last island in the network, which now spans the whole of Maine’s coastline. In 2009, Smuttynose, on the New Hampshire border, was added to the trail, and islands well into Canada in Passamaquoddy Bay form a side trip. (The unforgiving cliffs of the Bold Coast, east of Machias, limit through-paddling to all but the most experienced sea kayakers.) Also joining the network this year or next will be a cluster of islands in Cobscook Bay on Maine’s easternmost edge, home to powerful tides–a challenging, hazardous destination for boaters.

Technology has also intruded. In 1989, I had no GPS, no cell phone, no iPod–no electronics save for a small weather radio. But last year, my dry box was crammed: Out on Halifax Island I read that day’s New York Times on a Kindle, checked e-mail, even made a call to Ireland. Convenient, but somehow it felt wrong and unclean. Technology has made the islands smaller and less remote, as if the world has suddenly constricted around them. I vowed to leave anything with a battery behind next time.

That afternoon I stowed away my electronics in the beached kayak, then set off to spend a few hours poking around, scrambling up ledges, marveling at smooth granite cobbles, basking in the lambent light of the Maine coast. I found a dead lobster, prehistorically large and with claws as big and powerful as a forklift, and I gathered some cranberries and scraggly blueberries from bogs and bushes edging the shore. For a moment, it seemed that 20 years had been instantly erased.

“There hasn’t been much change,” noted Dave Getchell, when I asked him what he thought had changed over the past two decades. “And that’s good news. The islands I’ve seen have been very much the way they always were.”

I’m looking forward to filing a similar report 20 years hence.