Andre the Seal | 25 Years with Andre

Andre the seal may have been one of the longest-running, free attractions that Maine has ever had. We look back in this 1986 Yankee classic.

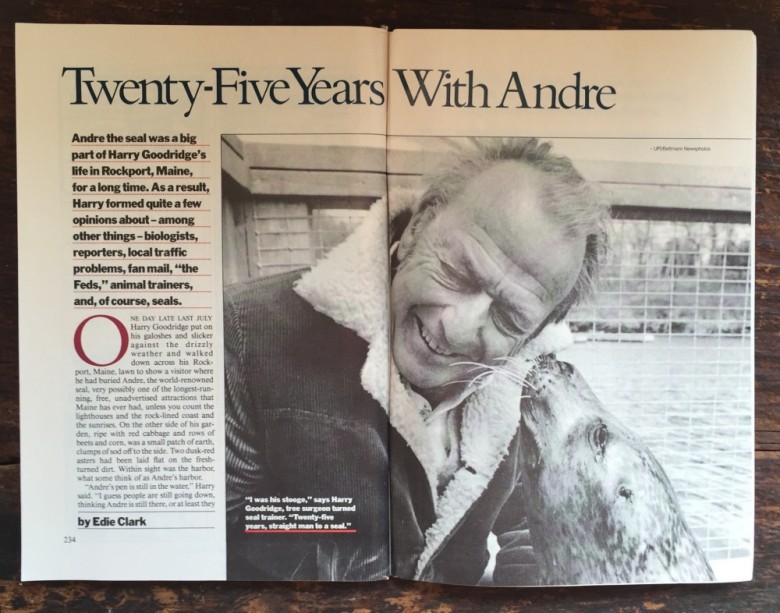

Harry Goodridge and André the Seal (1974)

Photo Credit : Photo by Lew Dietz courtesy of the Goodridge Family Archives / CC BY-SAAndre the Seal was a big part of Harry Goodridge’s life for more than twenty-five years. As a result, Harry formed quite a few opinions about — among other things — biologists, reporters, local traffic problems, fan mail, “the Feds,” animal trainers, and of course, seals.

One day late last July, Harry Goodridge put on his galoshes and slicker against the drizzly weather and walked down across his Rockport, Maine, lawn to show a visitor where he had buried Andre, the world-renowned seal, very possibly one of the longest-running, free, unadvertised attractions that Maine has ever had, unless you count the lighthouses and the rock-lined coast and the sunrises. On the other side of his garden, ripe with red cabbage and rows of beets and corn, was a small patch of earth, clumps of sod off to the side. Two dusk-red asters had been laid flat on the fresh-turned dirt. Within sight was the harbor, what some think of as Andre the seal’s harbor.

“Andre’s pen is still in the water.” Harry said. “I guess people are still going down, thinking Andre is still there, or at least they go down to look. I keep right away from it. I don’t want to get into any conversations.”

Andre the seal had been missing from Rockport Harbor since June, when he got into a fight with another seal. All month Harry had been out checking tips from people up and down the coast who thought they’d spotted the aging seal. Each lead brought hope, and Harry marked every one on his calendar. “I checked out four dead seals and then of course I checked out a lot of live ones. It would be an old seal, but it wasn’t Andre.” More than a month after Andre’s disappearance, a man who’d gone for a walk on a remote section of Rockport beach found Andre, washed up on the shore. “Some animals go off somewhere to die,” Harry explained. “Well, he came close to not being found because he was off where nobody bothers to go. He must have found a quiet spot and given up the ghost. Four of us went down and carried him up over the rocks, put him in the truck, and brought him home. It wasn’t easy.”

The grave is next to that of one of Harry’s beagles, but there is no marker for that one either. “My daughter has all kinds of plans for this. She wants to get a rock from under the ocean and bring it up here and put a plaque on it. But, well,” he said, bringing his shoulders up into a shrug, “I don’t know.”

Harry Goodridge has never been big on sentiment or celebrity — in many ways the pageant that surrounded Andre the seal was his nemesis — but it isn’t that he doesn’t care. It’s just that Harry isn’t one to coocheecoo an animal, especially not Andre, and he’s certainly not one to be caught weeping over a grave. But he can’t deny that the arrival of Andre the seal 25 years ago brought a bigger change to his life than that of his wife of 45 years or his children or his grandchildren. “Raising the kids was nothing,” he said. “But Andre, he was something else.”

May 16, 1961 , was a warm and hazy day. The bay out beyond Maine’s Rockport Harbor was flat and calm. Just before low tide, Harry, then a 45-year-old tree surgeon who took on skin-diving assignments as a side business, motored out toward Robinson’s Rock, a well-known spot where harbor seals go for sun and rest. He was looking for a seal pup, a companion to take with him when he dove, and he’d seen a newborn pup there two days before. He was hoping to spot him again. “I saw the small, sleek head fifty feet dead ahead, only its dome and round eyes above water,” Harry wrote 15 years afterward in his book A Seal Called Andre. “The seal pup raised his head as if to get a better view. The eyes that met mine showed no alarm. I looked around for the pup’s mother. No sign of her. Then a curious and totally unexpected thing happened. Instead of submerging, the pup swam directly toward the boat. I swooped down with my net and swung the little orphan aboard.”

[text_ad]

Thus came Andre the seal who, as you know, if you’ve paid even a little bit of attention to the news over the past 25 years, has delighted tourists with his harbor tricks and coastal migrations for much of that time. Within those rather lofty historic dimensions it seems remarkable, but back then, in 1961, it was kind of ho-hum for the Goodridges.

Aside from Andre, Harry had five kids, ages 7 to 19, and they were used to their father’s animals — there had been a robin named Reuben, a pigeon named Walter, and a sea gull named Sam Segal. Even a bat that he’d trained to eat flies from his hand. The seals were more fun. Before Andre, their father had brought home Marky and then Basil. The year before, Life magazine had come up and taken pictures of Basil and Harry underwater and made a big picture story out of it and called it “Skin Diver’s Best Friend.” Skin diving was a brand-new sport, and the whole idea of man befriending seal, or vice versa, was, well, news. But shortly after that, Basil was eaten by a shark on one of Harry’s shark-hunting expeditions.

Now here was Andre. Andre swam with them and went sledding with them. He splashed around in their bathtub and watched Flipper with them on TV in their living room. He rode around in the back of the station wagon, startling neighbors with his forthright gaze. And, like a dog, Andre the seal was trained. Harry taught him to shake hands and hide his eyes with his flipper as if in shame. He learned to leap through a motorcycle tire like a dolphin. Crowds gathered at the town landing when Harry went down to feed Andre. Word spread about this, and by the time he was a year old he was on his way to becoming a star.

In those early years, he spent quite a bit of time inside the Goodridges’ house, which is just up the hill from the harbor. The first year he was up at the house just about every day, sometimes all day. After a while he’d disappear during the day. “That was OK because I figured eventually he’d go wild anyway,” Harry recalled later on that chilly summer day, after his visit to Andre’s grave. “But then he’d come back at night and get up onto the float and wait for me to come down and pick him up. Every damn night. I always had a fear that someone from a zoo or an aquarium would grab him so I kept my eye on him and took him home. I could carry him under my arm back then.” Harry stopped a minute. He was in his home office which used to be headquarters for his tree business from which he is now retired. In those early days, Andre used to doze beside the desk here while Harry worked on his books. Most of what surrounds Harry now has to do not with trees but with Andre. Though Harry’s children are all grown up and he’s got grandchildren in high school, there is only one picture on the wall: a lifesize framed photo of Andre the seal. Harry laughed and continued, “He still liked to come up here, but toward the end it took four men to carry him.”

“But that was the first year,” Harry said, shifting back into the past, “and when winter came, the harbor froze over and the ice cakes were banging together, smash, smash, smash, and I didn’t see him again for five months.”

Photo Credit : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harry_Goodridge_and_Andr%C3%A9_the_Seal_(1974).jpg”>Photo by Lew Dietz courtesy of the Goodridge Family Archives / creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en”>CC BY-SA

Whatever perils Andre survived in the wild will remain unknown, but those he survived within the kingdom of mankind at times seemed insurmountable. It wasn’t just the ice but also the lobstermen and the fishermen, some of whom got plain fed up with Andre and the way he’d sleep in their boats at night and pull on their oars when they were trying to row out to their boats. Maybe give them a good splash, just for fun. There were threats and there were some unpleasantries. Harry, who was the Rockport harbormaster back then, began to fear for Andre’s life.

Through all this came the idea of wintering Andre at an aquarium. Seals are nonmigratory, but Andre became half-migratory. In the late fall, usually November, Harry would load Andre into the back of his station wagon and drive him down the turnpike to the aquarium. And every spring Harry would go back down and take Andre to a safe harbor. Harry would guide him down to the water’s edge and he’d say, “Go home, Andre!” and Andre would flop into the water and disappear. Harry would drive back up to Rockport alone and wait. And every time, once within four days and once not for two weeks, Andre the seal made his way back home to Rockport, mystifying biologists and providing the press with something to watch every spring. In all, Andre spent six winters at the New England Aquarium in Boston and four winters at the Mystic Aquarium in Mystic, Connecticut, from which he returned at last and for good, early last winter, after refusing to eat until Harry came after him.

Even Harry never imagined it would go on for as long as it did. “Many years I’d say, well, next year I’ll have him do this or do that and then I’d say oh, no, what if he doesn’t come back. I kept saying that and saying that all those years. I mean, there was always that chance that he wouldn’t come back.”

Nor did he imagine that Andre the seal would be around long enough to be the ring bearer at his daughter Toni’s wedding. Toni was seven years old when Andre came to the Goodridges. She was 26 when she got married, and it might be one of the favorite tricks Harry taught Andre. “The wedding was on a town float and we had a diver underwater with the ring. Andre was on the float with the wedding party. So when the minister asked for the ring, whump, he was overboard and in a minute or so he was back with the ring. He got up onto the float and humped over — not to me! — to the best man, just like we’d rehearsed it.”

And then there were the shows that Andre and Harry put on in Rockport every day between April and October. “We didn’t charge for the show, never,” Harry said. “We passed the hat, but I couldn’t charge for the show anyway, not with the facilities we had there. People had to stand up, and half the time there was old lobster bait stinking up the place. It could get pretty nasty, but they still came. And I didn’t advertise, heavens, no. People came from all over the world, really.” Harry stopped to dig around in his desk and came up with a couple of snapshots of a crowd on the dock that might be described as a mob. “There was never a sign saying what time the show was. People just knew. What? How did they know?” Harry looked disgusted. “Do you realize how many TV shows he’s been on? ‘ Real People.’ Charles Kuralt. Dan Rather. Tom Brokaw. And every major magazine except Time.” He stopped, giving the snapshot a hard look.

“What could I do? I couldn’t just say the hell with you people. If I had stopped doing it, the town would have been deluged with people wanting to know why.” Harry flung his arms around as if he might be able to find the answer to all this out there somewhere. Finally he said, “I just didn’t know how to not do it, that’s all.”

Harry relaxed into a trance of reminiscence, revealing a shade of a smile … He must have liked doing the tricks, he must!” Harry made a clucking sound. “Especially when he had to do special shows or TV appearances and they’d make him do things over again. I’d feel so bad for him, but he didn’t care. He knew something was special and he loved the attention.”

Harry’s a handsome man with eyes the color of a tranquil Mediterranean Sea, but he can be kind of gruff. Andre was known to bite people when he was in mating season or when he was shedding, and as some reporters know, Harry’s been known to bite, too. “People magazine called up about a year ago and they said, ‘We’re coming up to do a thing on Andre,’ and I said, ‘Well, you better bring me a check for $500,’ and the guy said, ‘What are you talking about? We can’t pay for news!’ Well, that was the end of them. I duck a lot of it! They’re all so damned arrogant. A crew from CBS showed up here the other day, after Andre was found dead. They came marching across the lawn and I said, ‘Hey, you never paid me for the last time. I’ve got nothing for you. I don’t mind if you get right off my property.’ They turned right about-face and walked right off. What they don’t understand is that I didn’t do this with any idea of having Andre become a star or a celebrity and I still don’t give a hoot,” Harry said.

If it wasn’t the newspeople he was trying to chase back, it was the Feds. “They passed this law in ‘72 that said you can’t keep a wild animal without a license. These three guys showed up one day and they said look we think you’re breaking the law with that seal of yours and I said I’ve had him long before that law was passed and they said well you let him out don’t you and I said yeah and they said and you let him back in don’t ya and I said yeah and they said well that’s capturing a seal! Well, by the time they were done with me they wished they’d never met me. So, they forgot all about that. Then the Department of Agriculture got after me telling me I needed a license to display an animal and I said I’m not gonna get a license and we went back and forth until the press got hold of it and boy, did they back off, awful fast. Senators went right to Washington and said. ‘Come on, now. This has been going on for years. Leave him alone!’ So, after a while, they didn’t even send anybody down here.”

Animals are the ones Harry gets along with. To him, it’s easy. “It doesn’t take anything special. That’s the way animals are, if you take them over when they’re young enough. Seals, ducks, hell, even crows.” Harry ought to know. He’s had two, one named Klinker and another named Columbus who came to him when he called and went for walks with him perched on his shoulder. “If there is a quality that’s more important than others, I guess it’s patience. But it really doesn’t take much to train a seal. I knew I had something way back when I was diving and I found out how these seals would get so tame, right off. In a lot of ways he trained me.” Though he says he is past the age where he would again raise a seal, Harry thinks that almost any seal could have been trained like Andre. “Of course, they’re just like people. They all have different personalities, but he wasn’t the only seal I trained. I look back at what they did for me and I can’t believe it. Andre the seal knew the difference between blowing his nose with a handkerchief and blowing a whistle. When he’d blow into a handkerchief, he’d make the Bronx cheer sound; when be blew the whistle he’d just blow and not make any sound — now how did he know the difference? I’m darned if I know. He always made me do the thinking. He had his way of talking with me. Just like this thing last fall down at the aquarium. They called me up and told me he hadn’t been eating and had lost a lot of weight. I knew right away that he was homesick and wanted to come home.”

One of the bookshelves in Harry’s office is loaded with yellowing news clippings about Andre, and every day more letters come in. The thing that intrigues the kids is that it’s true,” Harry said. “It wasn’t a damn Disney Donald Duck thing. Andre was real! Some people couldn’t believe it,” Harry said. “You know that lion, Elsa, in Born Free? Well, maybe I’m jealous, but Elsa went on for only two years. Cripes, this just went on and on and on.”

He also has a drawer full of video tapes, including one full-length feature, entirely in Japanese. That one is Harry’s favorite. “I won’t be playing them for a while, I guess. I haven’t busted up yet but almost. I got a letter yesterday that almost got me going.” He went into the kitchen and came back with a cardboard box stuffed full of letters. “These have come in just in the last week.” He picked one out at random. It was postmarked Springfield, Massachusetts, addressed to “Andre’s Owner, Rockport, Maine.” It was a store-bought card, edged in violet. “With deepest sympathy” the letters scrolled out across the front. “Most of them are like that,” he said. “But this one was a little different. This woman wrote and said, ‘If you don’t mind, I’m writing a note to you from Andre.’ It was a kind of a thank-you to me from Andre, for letting him live free, and she just knew how to do it, she knew just what to say. It kind of got to me.”

Harry is 70 now, though there isn’t much sign of it except for the gray hair. He feels that in some ways — though Andre did not suffer from lack of attention, hell, no — the remarkable seal was never quite given the respect he deserved. “Those marine biologists would never lower themselves to ask me anything about Andre. I should think they’d have been on top of this thing all the time, asking me questions, because I can answer them and they can’t. But . . . no-o-o-o.”

Photo Credit : Brenda Darroch

Last fall Andre went blind from cataracts. At least, that is what Harry says. “I knew he was blind ‘cause he couldn’t see — I didn’t need anyone to tell me that.” Andre could still do most of his tricks, with only one exception: “He couldn’t jump through his hoop — he couldn’t see it. But he could still shoot baskets. I mean, after all these years, he knew where the basket was.”

At the time of his death, Andre was said to be the oldest living harbor seal. “They know of a couple of seals that have lived to be 40 or45,” Harry explained, “These were seals that lived in aquariums. Seals that live in the wild, nobody knows their lifespan. Andre lived a life that most seals don’t live — aquarium seals are one thing and wild seals are another, but he knew both.”

Harry’s been to visit aquariums around the country. In fact, Andre the seal was named after Andre Cowan, a Tahitian trainer at Marineland. He corresponds with some of the trainers and sometimes they swopped tricks. He got the idea to teach Andre to play the ukulele from an aquarium in Seattle. But there is a distance between Harry and this other breed, the professional animal trainer. “At the aquariums they don’t call them tricks or stunts anymore; they call them ‘behaviors’.” Harry said the word with the nasal disdain of a stuffy old dowager. “I guess that’s supposed to dignify it or something. Well, Andre and I still called them tricks. ‘Trained seal’ might be derogatory to some people but not to me. Andre the seal was certainly trained. In fact he probably knew a lot more ‘behaviors’ than most other trained animals — I don’t know what his repertoire was, a hundred tricks, at least, I suppose. I couldn’t remember half of them myself. Toward the end, I couldn’t really think of anything else to teach him. The last thing I taught him was to wave good-bye.”

About ten years ago Andre the seal was immortalized in stone. A granite statue one-third larger than life was carved — while Andre posed on his float — by Jane Wazey, a well-known sculptor, and was dedicated in place down by Rockport’s boat landing, right where other towns are likely to have statues of their war heroes. A rim of evergreens was planted by Rockport’s Garden Club. After Andre the seal died, fans streamed there, solemn faced. Some brought fresh-cut flowers in vases and set them around his plump likeness. Others stopped and stroked the smooth stone or patted his arched head. Couples took pictures of each other beside the flower-strewn stone. A woman from New York stood staring at the eerie likeness. “I never got to see his show,” she said. “When I heard he’d died, I said, ‘Shoot, I wish I’d gone!’ ” Another woman nearby overheard her and said, “Oh, I used to love it when his trainer would say, ‘Andre, tell me what you think of Flipper,’ and he’d go,” she put her tongue between her teeth, “Pthwttt!”

The statue, which faces out toward the harbor, was not meant as a memorial, and the plaque which accompanies it speaks of Andre as if he were still there. In inch-high bronze letters, the story of Andre the seal is spelled out, all told in the present tense.

Back at the house, Harry had already answered that question — should the plaque be changed to past tense? He was surprised, possibly offended, by the idea.

“Why? It’s as it should be!”

This article first appeared in the November, 1986 issue of Yankee Magazine.

Did you ever see a performance from Andre the Seal? Share your memories in the comments!