Here in New England: Brendan Loughlin

This Connecticut artist survived hard times to find his true life’s work.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

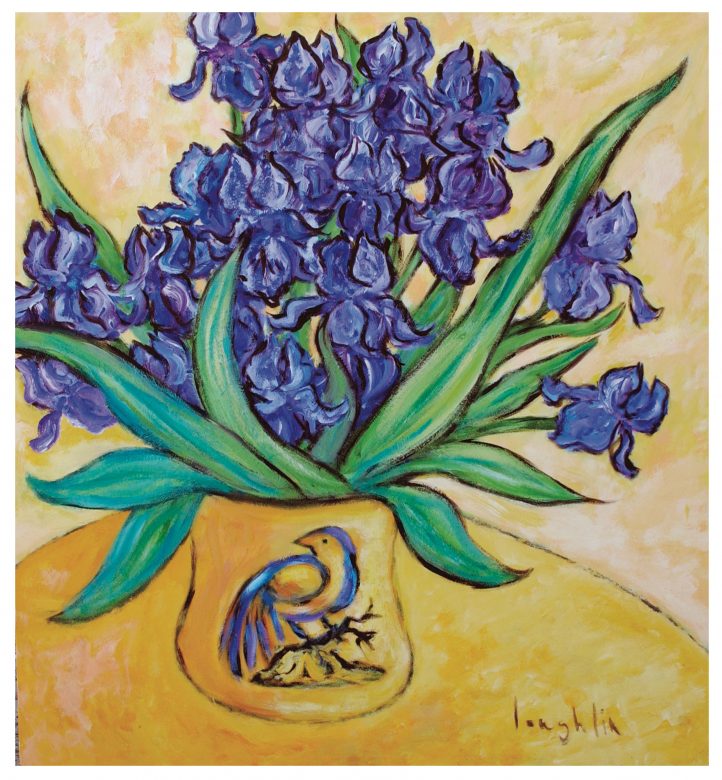

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanWhat I remember most about meeting Brendan Loughlin is that everybody in Guilford, Connecticut, seemed either to own one of his sunflower paintings or had studied painting with him. I attended one of his outdoor classes, and everyone was intent on their work, and smiling too. His “Pastac” technique — painting with shellac mixed with pastels — eliminates fear of failure, since one can start over in a flash. Even I did a Pastac (though it began as a seascape and ended up a mountain). Loughlin’s enthusiasm is contagious. Today he still lives on the Connecticut coast, painting and teaching in Westbrook. —Mel Allen

The boy’s name is Brendan Loughlin. It is the 1950s, and he lives in Wallingford, Connecticut. He loves to draw, and escapes what he later calls “a working-class dysfunctional family” by hiding out in the woods, drawing cars and airplanes. As a teenager, when his buddies talk about horsepower, he gushes about design — the wraparound windshields, the grilles, the taillights.

Brendan marries at 21 and has two daughters. He buries his dreams of becoming an artist. He drives trucks, moves into shipping and receiving, sells restaurant equipment — trying one thing after another, hoping to find a fit. Eventually he starts a one-man company refinishing and spray-painting kitchen cabinets. Still, a dank depression settles in, and he feels as though he is “in the teeth of a beast.” After 20 years his marriage ends.

He marries again, and now he has a son and another daughter. His second wife has an art degree, and her shelves are full of art books. Brendan pores over them, studying, learning everything he can about the history of art. One day, in his mid-forties, he takes a T-shirt and paints a tiger’s head on it. “I loved it,” he says now. “I knew it was good, really good.” His wife tells him it’s terrible; she locks up her paints and says he is not to touch them again. In time, there is a second divorce.

Photo Credit : John Madere

Winter, 1992. His life feels like a constant cold chill. His mother in West Haven is living alone, sick with diabetes, and he moves into a second-floor room to look after her. His kitchen cabinet business founders. When he’s not caring for his mother, he seeks solace reading art books in his room. In the fall of 1994 he starts, hesitantly, to paint: “I told myself, I have to be able to do portraits to know if I’m a painter. I will allow myself one hour to draw a portrait. I found a photo in a magazine of Bill and Hillary Clinton. I got a pencil, I looked at the clock, and then I started shaking. I was a bundle of nerves. Finally I released the fear, and bam, it happened. I did a drawing and I liked it. I said to myself, ‘I am now an artist.'”

By 1997 Brendan’s mother is too ill for him to care for on his own, and she moves into a nursing home. He works in the men’s department at Filene’s, but it doesn’t take. “I had no idea how to make a living,” he says. He loses his car. The electricity is shut off, then the phone; and then the bank auctions the house. He must vacate it by Thanksgiving. He is 57; everything he owns fits into two canvas sacks, and he stuffs them into his daughter’s car, where at times he is forced to sleep. He moves into the basement of a friend’s home, until he finds sporadic housesitting jobs. When he sleeps, he dreams of painting.

He works part-time at a paint store in Madison, and also at the Guilford Handcraft Center, registering students for classes. At night, after locking up, he secretly sleeps on the floor, slipping out before sunrise. He remains certain that he “was meant to paint. I had the feeling this was going to happen for me.” In 1998 he moves into a one-room apartment in Guilford, telling the landlord that he’s an artist with no money, no security deposit, and no credit. The landlord takes a chance and rents him the room.

In the spring of 1999, to clear his head, he takes a bus to St. John, New Brunswick, and finds a cheap furnished room — “the kind bachelors rent for a month,” he says. He brings with him a drawing pad and pencils. “I was lying in bed,” he remembers, “sketching with a pencil, when I saw my future.” He buys chalk pastels and B-I-N, a shellac-based primer-sealer that he’d used when spray-painting cabinets. He mixes the pastels with the shellac and loves the texture, the explosion of color, how he can paint layer upon layer, the picture drying within moments. The pastels and B-I-N cost a fraction of what oils do. He trembles with excitement: “I was all by myself, nobody to talk to about it. I said, ‘I’m going to take this back. This is how I will paint.'” He returns to Guilford and is promptly put in jail for missing a child-support hearing. His landlord bails him out. He finds work refinishing wooden boats. He becomes a familiar figure on the streets of downtown Guilford, in his tattered, paint-splattered jeans and loose shirts, always smiling and chatting with passersby, experimenting day after day with his pastels and shellac.

In the days following 9/11, Guilford’s town green fills with American flags. Brendan thinks, “We need to have balance, need to show joy, too — that we still believe.” He hauls a slab of plywood, big as a refrigerator, in front of a florist shop at the edge of the green and paints sunflowers — vibrant, luxuriant sunflowers — and people drive by, honking and waving. MaryLou Fischer, who owns one of Guilford’s leading galleries, is moved by how people react to Brendan’s work, and she wants to see more. Soon the gallery’s walls are covered with Loughlins, and the people of Guilford and beyond come in and buy, one after the other.

Photo Credit : John Madere

Brendan becomes Guilford’s artistic Johnny Appleseed. Along the streets of Guilford, on shop doors and gates and fences bordering the green, Brendan plants landscapes that sprout everywhere — sky, ocean, great ripples of flowers, as if he’s thanking the town that embraced him. “Anything that doesn’t move, I’ll paint it,” Brendan says. “Primitive, joyful, emotional — I think that’s the best way to describe my work. I want to stop people in their tracks. You can’t walk downtown Guilford and not be stopped in your tracks.” Wherever Brendan walks in the village, people call his name.

Autumn 2007. Brendan is 66. His hair is white, his trousers are still tattered, covered in paint; he’s as buoyant as a golden retriever. Around him on this patch of parking lot, beside a popular café called Tastebuds, a clutch of people have gathered, as they do most days, men and women of all ages, to paint under Brendan’s coaxing eye. Everyone, it seems, wants to paint with Brendan. “I never had an art lesson,” he says with amazement today, “and here I am teaching people, some with four years of art school.”

He’s convinced he has created a new art form the world will embrace, if only the world knew about it. He calls it Pastac, a blend of pastels and shellac, and now he has learned that by adding the tints used by commercial painters he can create exotic, rich, compelling colors. He says it’s his mission now to bring it to others. “There’s such an elitism and fear about painting,” Brendan says. “People say, ‘I can’t paint.’ My goal is to show people they can. There’s no other form of painting like this. One day we’ll see painters everywhere using acrylic, oil, pastel, and Pastac. I know it will happen.” He starts his mission here, in Guilford, and in nearby towns, a few painters at a time.

One of his students looks up from her painting. “The whole thing he preaches to us,” she says, “is ‘Never worry. Paint without fear. You can fix it.’ This is amazing. You feel you’re doing something wonderful with Brendan.” Brendan gushes about a recent class: “This woman, she was on fire. How she worked the brush! She couldn’t believe it, and when her husband came, he couldn’t believe it. Yesterday may have changed that girl’s life! Pastac is the only painting method I know where you can’t make a mistake. It takes away fear of failure.”

Brendan is in his apartment at the south edge of the green. Canvases, some complete, others in progress, poke out from everywhere. He allows himself just a few square feet of kitchen space; everything else is for painting. I haven’t held a brush for nearly half a century, yet here I am. Brendan gives me a jar of B-I-N. He hands me pastels and small tubes of tints. I abhor my firsttentative attempt. I’m self-conscious. I paint over it with the white B-I-N, and my crude strokes vanish. I start again. This, I see, is Brendan’s finest gift to Guilford. So many people who own his paintings, who study with him, knew him when he lived on sardines from the food bank, when he curled up in his daughter’s car on frosty nights, when he was everyone’s eccentric local artist. He shows them every day that you can make your life a breathing canvas, and sometimes if the will is strong, you can wake up one day, paint a sunflower bursting with hope, and start over.

To see more of Brendan Loughlin’s work, go to brendanloughlin.com.

How inspiring! I too am at the point in my life where I want my art to be more than something that just sits in my closet. I appreciate his determination to pursue his desire. Without a degree behind me, I completely understand the intimidation and feeling of elitism of painting. BUT, as I will use his story to inspire me to never give up on my dream of creating a career from my art! Thank you for sharing this story with us! Sincerely,

http://kellyschwark.com

I was sitting in my library in Middletown, NJ last Sunday, just hating the cold winter winds and snow squalls outside, and needed to rid myself of the cabin fever I was feeling. I am from New England ( Vermont ) and recently moved to NJ. so I am also in a new area trying to adapt to the new surroundings. I just wanted to read some fun stuff, so I chose Yankee Magazine for its familiar places inside its covers. I came across the article on Mr. Loughlin, and was totally inspired to pick up my favorite remedy for stress again, ART! His story was amazing, and had me welling up with tears with all his struggles of the past. I am thrilled he finally feels at home as an artist…I have had many of the same feelings…the feeling that I feel my art is trapped inside me, wanting to come out! I have been an ink artist for the most part, ( Very unforgiving medium ) so I was intrigued by this pastac combination as I read his article. I am going to buy the materials, and create something for the walls in my new house! Thank you Brendan…for sharing your incredible talents with us!

Love & Light,

Marguerite

I can’t celebrate someone who doesn’t pay child support.

A BIG WOW to Brendan. This is the type of person I would like to meet. Someone who has emerged from next to poverty to find himself and his trade and give back.

Amen to you, Brother,

Lucyna