Welcome to Cambodia Town | A Celebration of Cambodian Culture in Lowell, Massachusetts

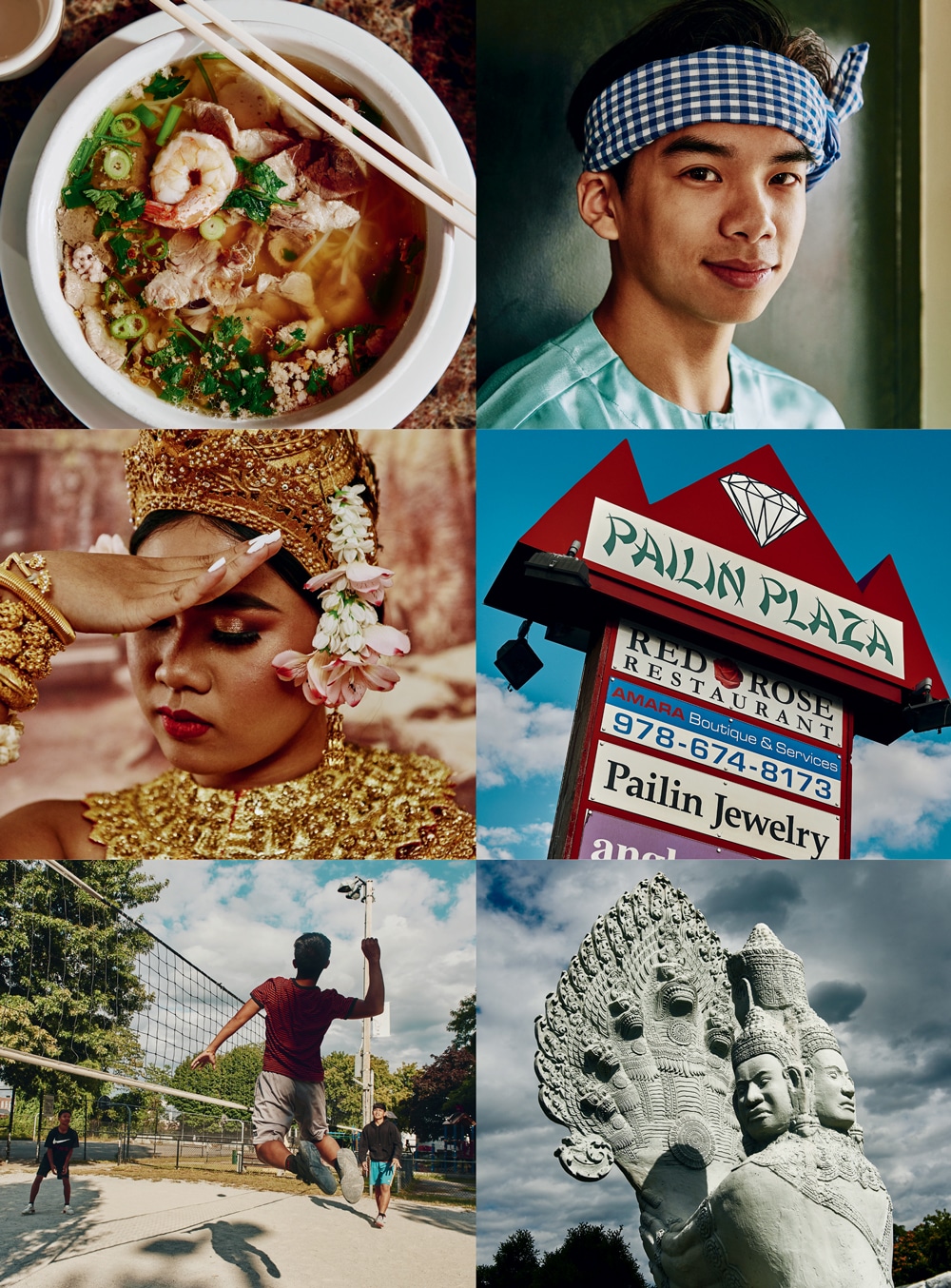

On a few blocks in Lowell, Massachusetts, lies one of the nation’s richest outposts of Khmer culture and cuisine.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Soben Pin orders two bowls of Phnom Penh noodles from a woman she calls Bang, meaning “big sister” in her native Khmer. Soben is cofounder of the biweekly KhmerPost USA, the widest-circulated Cambodian newspaper in America. She’s also my dining mate one soggy May morning at the Red Rose Restaurant, a tucked-away oasis of Cambodian cooking in Lowell, Massachusetts.

The restaurant is part of Pailin Plaza, the commercial heartbeat of a cultural district known as Cambodia Town, which holds the largest population of Cambodian immigrants and refugees and Cambodian-American citizens on the East Coast. After Long Beach, California, it is the second-largest Khmer community in the country.

The district sits near the masonry banks of the Pawtucket Canal in downtown Lowell, a 19th-century cobblestoned mill town still reviving its economic pulse in the post-industrial era, with former mills now rehabbed into art galleries and start-up offices, third-wave coffee shops, and a good cheesemonger. Concentrated on Branch, Middlesex, and Westford streets, Cambodia Town fringes the city-center renovations with its own snapshot of a modern American subcommunity: a purple-chalk hopscotch grid near a park entrance; squat retail buildings; Khmer translations under signs for a pizza shop, a hairdresser, and the restaurant where I now sit with Soben, who is pouring our tea.

Soben has a broad smile, a sturdy sense of humor, and eye contact that’s direct and deep. She knows everyone’s family here, and she asks me about mine. A big stack of KhmerPost USA papers, fresh from the printer that morning, waits for takers in the restaurant doorway. Soben writes the English portion of the newspaper, while cofounder, editor, and longtime Cambodian journalist Roger Pin, her former spouse and current business partner, writes the Khmer portion. Headquartered just a few blocks from City Hall, the paper has more than half a million readers worldwide.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

At 10:30 a.m. the Red Rose is already beginning to fill with regulars cradling bowls of the pork broth–based noodle soup named for Cambodia’s capital city, Phnom Penh, where it’s commonly eaten for breakfast. When Bang had asked Soben in Khmer if maybe she should order the all-chicken version of the dish for me, “I told her no, no way, you’re getting the authentic Phnom Penh noodles,” Soben says.

Also called kuy teav, the soup arrives moments later in a haze of ambrosial steam. It’s rich and layered, the broth hot enough to melt pork bones. Tiny beads of flavor-rich fat cling to the sides of the bowl like pearls, balanced by a zip of vibrancy from somewhere in the stock’s hours of slow simmering. Bobbing in the liquid are dried shrimp, poached shrimp, ground pork, pork loin, thinly sliced pork liver, ribbons of tripe, cilantro stems and leaves, fried garlic and shallots, and a knot of rice noodles. On the table are aromatics and garnishes meant for toggling the flavor to one’s liking.

There’s a crisp tumble of chilled bean sprouts and lemon cheeks. A foil-wrapped tray holds fermented and pickled condiments brooding with chilies. I slurp silky noodles, my pen forgotten beside me, the kuy teav as ancient, nuanced, and varied as the country of its origin.

– – –

Fringed by Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and a long stretch of the Gulf of Thailand, Cambodia is a civilization with more than 5,000 years of history—including the infamous era of genocide under the Khmer Rouge regime, from 1975 until its fall in 1979. It was a time when those who could, fled.

The U.S. Census began counting Cambodian as a race and tracking its American-based population in 1980. In the following decade, nearly 150,000 people would leave Cambodia for the United States. Lowell’s own population of Cambodian immigrants and Cambodian-American citizens has grown to about 20,000, and the Khmer community is now one of the biggest economic contributors to Lowell’s reinvigorated economy.

“The Pailin Plaza area is probably the busiest retail area in the entire city of Lowell,” Soben says. “This community is built on incredible resilience; they’ll make a life out of this place.”

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Bang whisks away my empty bowl and brings me a tall glass of cold coffee brimming with crushed ice and condensed milk, which I suck down like nectar. Soben tells me that Roger is coming to join us after he meets with Prince Sisowath Thomico, who is visiting from Cambodia. (I’m amused by the social incongruity: I’m after … the prince?).

To train as a journalist in Cambodia, a country with little history of freedom of speech, is a trial by fire. Questions asked and information relayed becomes an increasingly high-stakes transaction. The independent Cambodia Daily was forced to shutter in 2017. The international broadcast Radio Free Asia has been banned by many Khmer radio stations. And Roger Pin is known as the only living journalist to have interviewed the totalitarian leader Pol Pot before his death in 1998—the same leader who, 22 years earlier, had presided over the regime that killed nearly two million people, including Roger’s entire family.

“I was the only journalist in the field at that time,” says Roger, after he enters the Red Rose in a plaid scally cap, wearing a crisply ironed blue shirt under his suit jacket, and pulls a stray chair to the end of our booth table. “I stood up against corruption and for people’s rights. Everyone had guns—I had a microphone and a tape recorder.”

I ask Roger how you have a conversation with a person who has killed your family. “You can’t talk together as a dictator and a journalist,” he says. “You must interact as a person and a person. Having a conversation means we can see each other as people.

“Whether you’re Cambodian or American,” he continues, “you don’t really know what life looks like until you ask.” That mental switch is a bridge, he says, to start communicating—and to keep communicating.

“You can only get slapped on one side of your face,” Soben chimes in. “You don’t give them the other side to slap, too. Cambodians in Lowell are survivors, and we’re all proud of our culture. We want to share it. And to me, [that] is to publish a free Khmer press in the United States.”

After our chat, Roger pushes back his chair to stand; it’s time to return to the prince. Bang writes our bill in pencil and, lunch rush oncoming, bids us a quick good-bye. Having immigrated from Cambodia in 2003, Bang—whose real name is Soknay Cheang—bought the Red Rose in 2011 with her husband, Kheang Hong Long, after working in a Boston-area factory making electronic car parts. “I didn’t want to do that,” she says, motioning to the bustle of the restaurant behind her as we depart. “I love food. I love to eat.”

– – –

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Cambodia Town has become one of America’s richest outposts of Khmer art, history, entertainment, and cooking, and walking through the heart of the district with Soben Pin is to be guided by the community’s Virgil.

Across the street from Pailin Plaza, the path to Roberto Clemente Park (referred to as Pailin Park by most Cambodian locals) is mottled with early-afternoon rain. On a sunny summer day, Soben says, as many as 300 people might pass through the park’s open space. There’s a playground with a big green slide. Volleyball nets host regular pickup games, and crews of old friends congregate weekly for games of bocce. But today it’s quiet, given the drizzle and the oncoming warning of darker clouds. Soben uses a laminated folder as an umbrella as we shuffle next door to Amara Boutique and Service, where her friend Monica Am curates an emporium of Khmer goods.

After she and Soben come together like magnets, Monica is introduced to me over a table of shawls with labyrinthine gold stitching. The boutique is a kaleidoscope: rich, vivid, multidimensional. It’s a place for the in-between moments of daily life, for browsing Khmer lesson books and travel guides and birthday gifts, for considering crushed violet or emerald green for the trim of traditional formal wear. There are evening scarves, temple scarves, and casual scarves. There are quartz figurines, wide bowls once used for carrying water, and Khmer cookbooks shelved near gilded platters depicting the ancient religious site Angkor Wat.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Monica left Cambodia for Lowell in 1982 but still returns three times a year to import Khmer items. A carved Buddha, a recent find from the Cambodian mountains, smiles patiently near where we are standing.

Asked what builds the community, Monica repeats the question and then says: “Cambodian-owned businesses.”

“There’s a common heart we want to preserve here,” Soben adds, motioning to a sculpture of the Bayon Buddhist shrine in Angkor Thom. The piece mirrors a 12-foot-tall Bayon monument rising high above the sidewalk outside, the result of a local fund-raiser. The serene faces peering out from the monument are a smooth, buffed gray. It’s like the community itself, Soben says: “It lasts. It’s here to stay.”

Again sheltered by laminated folder, we make our way from Amara Boutique to Pailin City Market, with its burlap sacks of white rice and crates of squat bananas. The supermarket is a vast stockpile of grocery staples, a headlong dive back into the aromatic haze of a bowl of kuy teav.

“This feels like childhood,” says Soben, selecting a caramel-burnished nom kong, a Khmer doughnut with a hole wide enough to fit a wrist through (kong actually translates as “bangle”). She lifts the knobby orb of a Cambodian guava for me to smell; the syrupy perfume of ripeness seeps through its tough skin. “This too,” she adds, and buys both for us to split. The doughnut crackles as it’s halved, bittersweet caramel splintering over the chewy fried dough.

Soben gestures across the street to Yummy Express, a Cambodian snack shop loved for its nom kong as much as its other street-food staples: stuffed baguette sandwiches called num pang, fried globes of sticky rice flour with a nubbly coat of toasted sesame seeds, blended ice cream drinks and smoothies in eye-shadow hues of avocado, red bean, and melon. The shop is closed, says a note written in Sharpie: They’re on vacation.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

Cambodia Town is markedly flush with privately owned businesses. Sereysophana Yauk and her husband, Tolayuth Ok, a lawyer, own Bopha Bridal Boutique, which boasts fresh floral arrangements, custom gowns, and an upstairs area for formal photos. (We wait out a hasty downpour here, chatting on a buttery-soft velvet bench.) Bora Chiemruom, a Khmer refugee who grew up in Lowell in the late ’80s, owns Kravant Boutique on Branch Street, a consignment shop for renting special-occasion Cambodian gowns. Just beyond the border of Cambodia Town are the headquarters of Flying Orb Productions, a Cambodian-American film and theater company that began production on their latest film, A Road Beyond, in 2019. Then there’s Simply Khmer, a restaurant owned by husband-and-wife team Sam Neang and Denise Ban that’s been highlighted by Boston news outlets as well as by celebrity chef and Travel Channel host Andrew Zimmern. (He ordered beef salad with tripe, rice porridge with pork, spicy head-on shrimp with garlic sauce, and, in a nod to the menu’s more Anglo-leaning items, hot wings.)

The Lowell-based Angkor Dance Troupe specializes in Apsara, a classical Khmer dance from the 11th century; the nationally recognized company performed it at the White House. A biannual 12-week dance program helps filter Apsara into the local community, as do performances such as last year’s Apsara Dancing Stones and a headlining spot at Lowell’s August Southeast Asian Water Festival. The festival itself, which the city has held for over two decades, draws more than 60,000 people from around the country with its longboat races, music, and myriad food stalls.

Photo Credit : Tony Luong

In 2017, Lowell—a city with a history of all-white governing bodies, despite a population that’s almost 50 percent minorities—inducted its first Cambodian-born city councilor, Vesna Nuon. That same year, councilor Rodney Elliott raised $45,000 from the Cambodian community for a monument to Khmer refugees, which was unveiled outside City Hall later that same year. The piece was created by Yary Livan, a Lowell resident and Khmer Rouge survivor.

Though we are still lodged in the weepy weather of late New England spring, Soben convinces Tolayuth Ok of Bopha Bridal Boutique to give us a lift downtown to see the monument. It’s a seven-foot, 6,000-pound sculpture of composite concrete dyed a baked coral-crimson, like sun on red clay. Names of donors both in and beyond Cambodia Town are inlaid on bricks skirting the base. On the monument itself, which has an etched Bayon face looming in one corner and a Cambodian palmyra palm tree in the other, there are four refugees: two children and a woman holding a baby. In a three-dimensional portrait of movement, each child has one foot moving beyond the sculpture’s frame—outward, somewhere.

“It’s one foot in America,” says Soben, “and one foot in the past.”

Great job exploring Cambodia Town. Wish I could walk into Yummy Express and get a nom kong!

I cannot wait to visit Cambodia Town and soak in its wonderful culture in my childhood stomping grounds of Lowell.