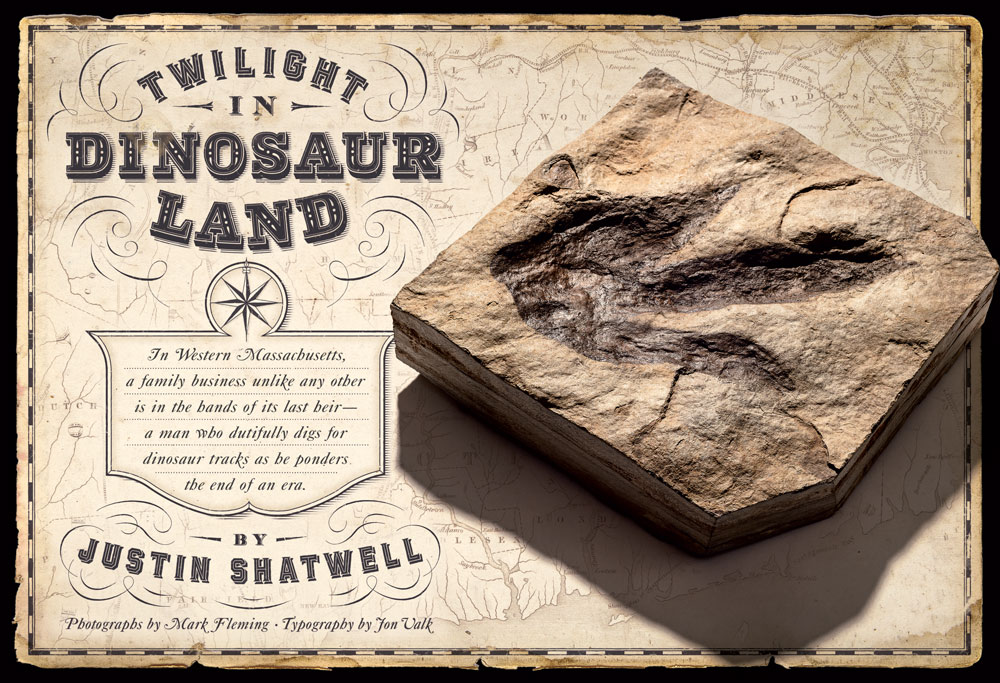

Twilight in Dinosaur Land

“It’s funny. When your parents die, you have all these one-time things you have to do.” Kornell Nash reclines in a weathered chair in his cramped office. A space heater in the corner keeps the late spring chill at bay. Beside the 15-year-old computer on his desk, a handful of fossils lie in an awkward […]

“It’s funny. When your parents die, you have all these one-time things you have to do.” Kornell Nash reclines in a weathered chair in his cramped office. A space heater in the corner keeps the late spring chill at bay. Beside the 15-year-old computer on his desk, a handful of fossils lie in an awkward pile.

Nash has spent the past few days sorting through his mother’s boxes. The dust and mold have brought on an unexpected case of asthma. “I haven’t had an attack since I was a child,” he says. It’s one more delay. One more thing to set right.

We won’t be digging today.

Beyond his office door, the shelves of the one-room store his father built here in South Hadley, Massachusetts, are sparingly stocked. There are plenty of plastic dinosaurs and semiprecious stones, but the one item that puts Nash’s business on the map—the one thing he alone sells—is in short supply.

Behind the store, Nash’s quarry stretches along the side of a small hill. It’s tiny, about the size of three tennis courts side by side. At one edge, six large footprints mark a curving path. They’re set deep into the shale. Looking at them, you can sense the weight of the beast that made them, see the purpose in its movements. Nash leaves them undisturbed—a surefire showstopper for the customers who visit him here.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Beyond the tracks, the quarry floor drops several inches. This is where Nash digs, when he can, carefully chipping away each pancaked layer of stone. Inch by inch he unveils more tracks—dagger-toed prints laid down as early as 200 million years ago. With a diamond saw, he carefully cuts them out, then cleans them up and places them on the shelves of his store, where they’re sold to anyone curious enough to buy one.

Nash learned his trade from his father. Seventy-eight years ago, Carlton Nash began mining this slab of shale; he built the family home and the store just yards away. Young Kornell grew up with an active dinosaur quarry in his backyard. Asked whether he remembered the first time his father let him dig out a track, Nash seems puzzled for a moment, as though he’d never considered it. “To be honest with you, I kind of grew up around it, and it was just kind of commonplace,” he says. To him, it was simply another household chore.

As a young man, Nash left home, never intending to take over the family business. But his father grew ill, and at 31 he found himself working here. At 42, he inherited it. Now, at 62, with his final parent having passed away, he’s left to wonder what’s next. The path before him is not set in stone. The purpose of his movements, unbound.

* * * * *

Carlton Nash knew exactly what he’d found when he found it. He’d been dreaming of it since he was a child. His father would bring him to the small natural history museum at Amherst College, where he’d listen raptly to stories about the school’s dinosaur-hunting professors plucking massive skeletons from dusty fields out west.

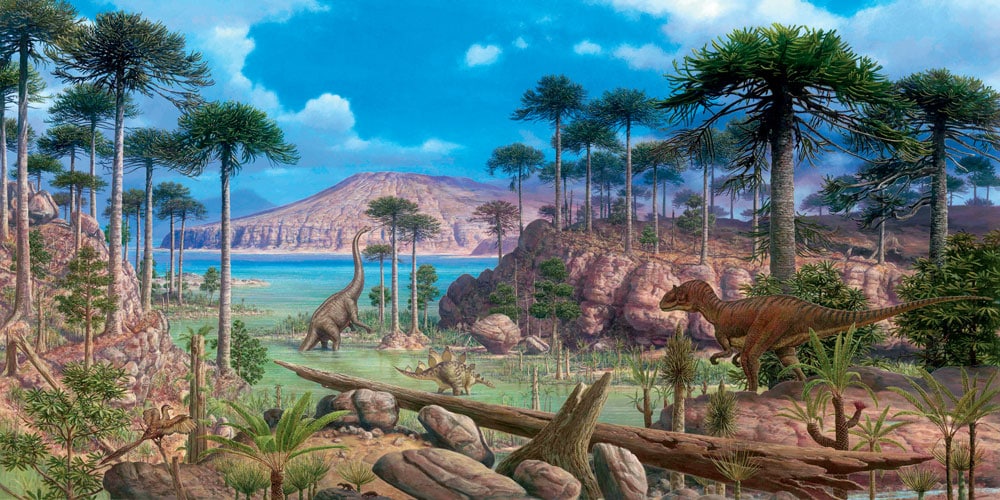

The bones always came from somewhere else. In the century and a half that people have been looking, fewer than a dozen dinosaur skeletons have been found in the Connecticut River Valley. During the Jurassic era, this area was a bleak landscape of mud flats and lakes. The wet soil consumed bones, but proved ideal for preserving footprints.

The first recorded discovery of a dinosaur track occurred in South Hadley in 1802, just miles from Carlton’s home. A young boy named Pliny Moody turned it up while plowing his father’s field. The story has inspired generations of dinosaur-crazed little boys and girls to launch mini expeditions into the forests of Western Massachusetts. But, for whatever reason, Carlton didn’t abandon the hunt as he grew older. He kept looking until, in 1933, he found it.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Carlton’s stone was something of a fluke. You can search acres of shale and find only a print or two, but here they were almost stacked upon each other. Millions of years ago, this spot was at the edge of a lake where dinosaurs would come to drink. It was a high-traffic area—a veritable dinosaur Grand Central Station. What’s more, Carlton’s stone was just sitting there. Shale is usually buried under several feet of sediment, but this piece had jutted up through the surface. It was a treasure in plain sight, needing only someone to recognize it.

It took Carlton six years to convince the man who owned the land to sell it to him. Though Kornell Nash would not be born for another 15 years, the most momentous event in his life had already occurred.

* * * * *

“I kind of like being a small businessman, but at the same time, this wouldn’t have been my choice.” Nash’s voice isn’t mournful or resigned, just matter-of-fact. He’s reached a contemplative point in his life. He isn’t cursing where he is; he’s simply working through how he got here.

It’s midsummer now, and Nash’s life is returning to normal. Several new tracks stand on the shelves of his store, each about the size of the framed photos in his office. A thin coat of varnish highlights the footprints, making them pop from the surrounding stone.

When Carlton Nash opened his store, he called it Dinosaurland. This was during the heyday of roadside attractions, and if he was going to reel in tourists off Route 116, he needed a name with some pizzazz. Today the tourists stick mostly to the interstate, and much of Kornell Nash’s business is done online. People still visit, but few enough that he doesn’t think twice about stepping away from the store.

Photo Credit : courtesy of the Botanic Garden of Smith College

Nash is out back in the quarry, carefully prying up a layer of shale about half an inch thick. He works from the edge, pounding a line of butter knives into the side of the stone, one every few inches. It’s a crude tool, but he’s never found anything that works better. He trolls tag sales and buys them in bulk when he can, leaving behind orphaned forks and spoons. He works slowly, one strike of the mallet at a time. As he senses resistance, he stops. “I might be coming up against a track,” he says.

Shale is composed of thin layers of petrified mud, one stacked upon the other. Dinosaur tracks exist as imperfections within this stone. Millions of years ago, the original print was a depression in the mud. Left undisturbed, it was slowly filled in by a new layer of dirt. When both layers hardened, the print was preserved within the rock where one layer dipped down to fill the gap in another. Nash’s job is to seek out these ripples and split off the layer that bore the print from those that filled it in. It requires patience and a gentle touch. “You start going fast, you start breaking stuff,” he says.

He gently applies pressure, and the shale lifts and shatters. He immediately begins to sweep away the dust. If each inch of shale represents some 10,000 years of geological time, Nash and his collection of improvised tools have taken an 8-square-foot section of the slab five millennia back in time in less than half an hour.

“There’s a really good one,” he says, running his fingers over the freshly exposed rock. “Center toe, left toe, right toe.” The track is only a few inches long—nothing a museum would put on display, but the kind of print that a curiosity-seeker might drop a few hundred dollars on. It’s hard to tell which dinosaur made it. Scientists can’t identify a species from a track; the best they can do is narrow it down to a family. Most of what Nash finds were made by some kind of thero-pod, a type of generally carnivorous two-legged dinosaur. The example Nash likes to give is the dilophosaurus, which Jurassic Park imagined as a frilled, venom-spitting beast.

As far as Nash can tell, he’s the only person who does this for a living. “If there were two of us doing this full-time, we’d both be out of business,” he says. The demand for dinosaur footprints just isn’t that large. Fortunately, neither is the supply.

He says he extracts around 300 to 500 tracks a year. They sell for anywhere from $50 for a damaged partial print to several thousand for a museum-quality one. For more than seven decades, the quarry has been like a money tree in the Nashes’ backyard. Every year they’ve dug here, and every year the shale has given them all the tracks they could sell. It’s never been enough to make them rich, but it’s kept them comfortable. Still, Nash reiterates, this wasn’t his first choice.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Kornell Nash

Nash sees himself not as a paleontologist but as a small businessman. It’s a point he brings up often. He looks the part: His hair is gray and trim, and he keeps a neat mustache. He wears a powder-blue polo shirt even as he’s prying up shale in his quarry. He looks more like an accountant than a dinosaur hunter, and that’s exactly how he likes to think of himself. “Yeah, dinosaurs are interesting, but they’re more [my father’s] passion than mine,” he says.

In college, Nash studied business, not geology. But just as his life was getting started, the wind went out of his sails. Two weeks after his 21st birthday, he was overcome by a lethargy he couldn’t shake; he was later diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome. “My friends were getting married, going out and getting careers, and I was taking a lot of naps,” he recalls. “It was kind of odd. I’m more energetic now than I was when I was 25 years old.”

By his late twenties he was sticking close to home, which meant that when his father fell ill, he was there. He took up the family business and supported his father, who was struggling with chronic shingles, as best he could. His two brothers had no interest in the business, so when his father succumbed to a stroke in 1997, Nash inherited it, as he puts it, “by default.”

“After Dad died, I said, ‘Mom, if I’m not married and you don’t have health problems, why don’t you just stay with me?’” he recalls. Like Nash, his mother had no passion for paleontology. She was a nurse in Illinois during World War II when she met her future husband. She had no sense that this is what her life would be. But she made the most of it, taking joy in meeting the people who visited the store. “Everyone found her what I call ‘Midwest friendly,’” Nash says. “Dad was a little bit more of the cranky Yankee.”

Photo Credit : courtesy of Kornell Nash

Nash’s mother used to tell him that as soon as he was old enough to see over the counter she put him to work in the store. He returned the favor by keeping the shop going so she could chat with customers well into her nineties.

“For about 30 years, I did get a lot of satisfaction helping my parents out,” Nash says. “It is kind of odd now. It’s kind of like I’m getting back to normal. I can do what I want with my life.”

Nash hasn’t decided what his next step will be. What do you do with the family business when the rest of your family has passed on? He never married and has no children, so there’s no pressure for him to preserve the business—now called the Nash Dinosaur Track Site and Rock Shop—for the next generation. The quarry is entirely his now; he’s just not entirely sure he wants it anymore.

He has no immediate plans to sell, but he fantasizes about what his life would be like if he never had to dig again. It’s always been his least favorite part of the business. “I find it very tiring,” he says. Asked what his dream job would be, he replies without hesitation, “I could see myself as the comptroller of some small company.”

Nash is aware of how crazy that sounds. All around the world, people toiling in cubicles are dreaming about adventures like digging up dinosaurs, while he stands ankle-deep in fossils and pines for spreadsheets. But the irony goes deeper than that. By his estimate, he’s extracted more than 9,000 footprints—far more than your average paleontologist. Though untrained, he very well may have more practical skill in excavating dinosaur tracks than anyone else alive, and yet it’s the part of the job he’d most like to stop doing.

Some wish he would.

* * * * *

“Out of nowhere, there’s this loud crack of thunder and the skies just open up.” It’s not raining—not now, anyway. The storm Fred Venne is describing took place millions of years ago. It’s all here, captured in the shale.

Venne holds his face so close to the stone his cheek almost brushes the surface. He picks the hidden story from the slab like a fortune-teller reading tea leaves. The raindrops came down hard and fast that day, he says. The marble-size craters they left behind bulge slightly to one side, indicating that the wind was blowing. Thin lines crossing the rock are the trails of bugs caught in the downpour. Small footprints divided by a solid line were made by a lizard dragging its tail. Perhaps it was racing for shelter, or maybe it emerged afterward to bask in the scorching sun that quickly dried the rain, baking this scene into the mud like a kiln.

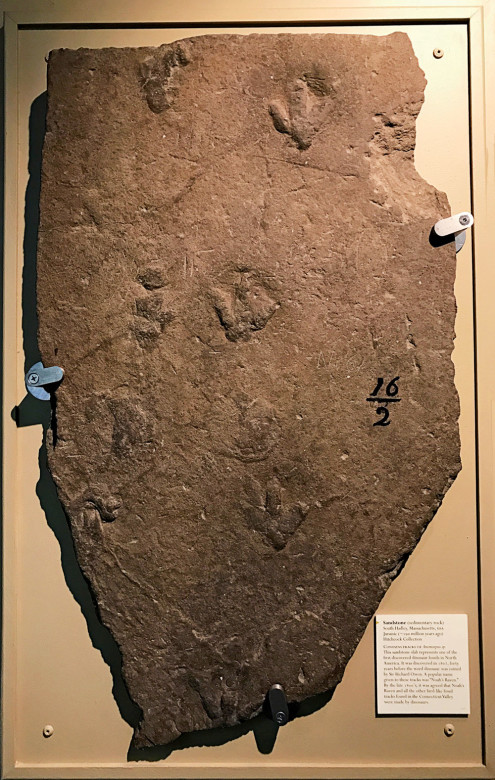

This pockmarked stone is the fossil of an event—“literally a moment that lasted, I would say here, two to five minutes,” Venne says. It’s one of dozens of prehistoric tracks on display at the Beneski Museum of Natural History at Amherst College, where Venne is the education director. The tracks are mounted on the wall in a basement gallery like works of art. None are labeled, save one: the first one, the stone that young Pliny Moody dug from his father’s field.

In 1839, the Moody track came into the possession of Edward Hitchcock, a geology professor at Amherst College who dedicated his career to collecting and studying petrified tracks. His research gave birth to ichnology, the study of animal tracks and traces.

Amherst College remains a leader in this niche science. For more than a century, researchers have come here to pore over the specimens Hitchcock collected, and each generation has teased some new discovery from the pale brown stones. Ichnology is a slow, methodical science and its practitioners are few. Venne says you can count the major players in the field on two hands, and everyone knows one another.

Kornell Nash stands on the periphery of this world, and his role is somewhat controversial. While his business is entirely legal (a fossil found on your land is your property), private sales are taboo in academia. The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology explicitly bans selling fossils because, it says, private ownership “deprives both the public and professionals of important specimens, which are part of our national heritage.” Others argue that private sales encourage the looting of protected sites.

Those who know Nash, like Venne, tend to give him a pass. Amid shrugged shoulders and comments about the situation not being ideal, most say he does more good than harm.

“It’s better to have interactions with people who run these businesses than to say, ‘I’ll have nothing to do with them,’” says Patrick Getty, a professor and ichnologist at the University of Connecticut. He’s one of a handful of scientists who have studied the tracks in Nash’s quarry, and he’s come to consider him a friend. He often sends students to do research there, and in return he answers any questions Nash has about paleontology. He’s even picked up a few tips from Nash. “In terms of excavating dinosaur tracks, he has a heck of a lot more experience than I do.” Now when he digs, Getty keeps a stack of butter knives in his field bag.

Getty says he knows paleontologists who would never set foot in Nash’s quarry. While he understands their objections, he thinks they’re shortsighted. Most paleontologists spend more time in the classroom than in the field, but private diggers serve just one master. They turn up fossils that would have otherwise stayed in the ground. “There are a lot of scientific discoveries that would have gone completely unnoticed if these people weren’t collecting,” Getty says. Still, he hopes that if Nash ever quits, no one will ever dig at that site again. “The ideal scenario would be if the town acquired it and made it a park.”

Nash has heard these arguments his entire life. “No matter what career you’re in, you’re going to have someone criticizing you,” he says. “I have no problem with what I do.” For him, it’s a question of abundance: Museum storehouses are filled with thousands of tracks identical to his, and he has untold thousands more in his backyard. “Academics have been studying them for a couple hundred years, and they have more than enough to study,” he argues.

His defiance goes beyond that of a self-interested businessman or even a son defending his father’s legacy. Nash believes he plays an important role. He takes paleontology out of the ivory tower and brings it to the people. There are only a handful of ichnologists in the world, but there are millions of untrained enthusiasts for whom owning a fossil is a life-changing event.

He claims parents routinely thank him because the print that they bought helped get their kids excited about science. “None of them ever become paleontologists. They’re usually engineers,” he jokes, but he feels pride in it all the same.

“Amherst I call the official museum. Things are behind barriers, ‘do not touch,’” Nash says. “I’m more like a nature center. Kids can come and touch things and experience it. And if they break something, it’s not the end of the world.”

He always has more out back.

* * * * *

Nash drives his van to the top of the highest hill in the cemetery. It’s a fine spot. Before the trees grew up, you probably could see the South Hadley green from here. The grave he’s visiting is taller than he is—a dark, somber obelisk inscribed with the name “Moody.” Etched into the stone is the family’s genealogy dating all the way back to 1633, when the first Moody moved here from England. Over the past 10 years, Nash has studied this grave so closely he’s found at least one typo in the chronology.

Nash’s obsession started after his father died. A family legend held that Carlton had grown up in the same house as Pliny Moody. Nash began to question whether that was true (it wasn’t). As he embarked on his research, he started to wonder what had happened to the fateful plowboy. After the discovery of that first dinosaur track, Pliny disappears from the annals of ichnology. Nash decided to go looking for him. What he found echoed his own life.

Pliny received a degree from Middlebury College before returning home to take over his father’s farm. Later in life, he heard about Hitchcock’s studies and that the college was collecting tracks. He figured if he found one, he could find more. And so he started digging. He’s known to have sold several to Hitchcock.

Pliny also had a son named Plinius, who, like Nash, never married and got sucked into the family business. “Maybe I did with my father what he did with his father,” Nash muses. “We were both born into dinosaur tracks whether we liked it or not.”

Pliny outlived his son, however, leaving him with no heirs. After he died, his widow sold the farm to one of his brothers, who lived in Troy, New York. The brother’s descendants still live there, so Nash tracked them down and asked if they’d like to come for a visit.

By chance, the Moodys arrived on the morning after Nash’s mother had died. Around 6:45 a.m., Nash got the call from the nursing home where she’d spent the last few months of her life. He went in, saw the body, and gathered some of her things. Then he met the Moodys at 9 a.m.

He showed them Pliny Moody’s grave before driving them up to the Beneski. Venne gave them a tour, and recalls that they were struck by a case of “edifice complex”: the awe of seeing one’s family name on so many plaques. They hadn’t known about Pliny Moody. They didn’t know that their ancestor was a folk hero to a tight-knit group of scientists. They didn’t know what he meant to people like Nash.

After the tour, Nash sent them on their way. He was eager to get back to his store. Never once did he mention his mother to them. “It was a special day for them,” he explains. He didn’t want to burden them. Besides, in a way it was as if he were spending the day with family.

Nash sometimes refers to Pliny Moody as a surrogate grandfather. Pliny certainly helped shape his life. Nash can plainly trace the chain of events: Pliny discovers the first track, the story inspires his father to open the quarry, then he himself continues the legacy today. “Who knows what I’d be doing if it wasn’t for Pliny Moody and my father?” he says.

Looking back on that day, Nash has no regrets. “It was an emotional day, but yet … my mother was 94. She lived a long and good life. We were very proud of her. It was just kind of time,” he says. “I wasn’t in a lot of emotional turmoil. But sometimes it takes some time for that to hit you.”

* * * * *

The sun is beginning to set over the quarry as Nash gathers his tools. The fading light casts long shadows over the shale. Nash pauses to inspect one of his new tracks. It’s a lousy specimen—only a partial print and not very appealing. It’s destined for his bargain bin. “I’ll sell it for $50 and make some kid happy,” he says.

Nash doesn’t know how much longer he’ll dig. “I could do it another 10 years, probably,” he says. “At the same time, I feel like I’m in the spot where if the right person comes along, I’d pass it on.”

He ruminates on the future of his quarry. He could chop up the property and sell it as housing lots. He could keep it together and try to sell it as a park. Maybe he’ll find someone who wants to keep digging. Maybe he’ll just keep it himself. He doesn’t know.

Should he continue in the life his parents gave him, or strike out on his own? It’s a tough question and one he’ll undoubtedly struggle with. But someday he’ll have to answer it. It’s one more chore, one more thing for him to set right. When your parents die, you have a lot of one-time things you have to do.

Justin Shatwell

Justin Shatwell is a longtime contributor to Yankee Magazine whose work explores the unique history, culture, and art that sets New England apart from the rest of the world. His article, The Memory Keeper (March/April 2011 issue), was named a finalist for profile of the year by the City and Regional Magazine Association.

More by Justin Shatwell