The Mount Washington Observatory | New England’s Weather Station

Take a behind the scenes peek at the Mount Washington Observatory, where every meteorological anomaly that has impacted our region has been observed, recorded, and shared by the staff since 1932.

The Mount Washington Observatory | New England’s Weather Station

Photo Credit : Jim DarrochWe New Englanders have an odd relationship with our ever-changing weather. Sure, we complain about oppressive humidity in summer and drifting snow in winter, but behind every gripe lies a touch of pride. We love trading stories about the Blizzard of ’78, asking our friends “is it cold enough for you?” and imparting Mark Twain’s famous quote about New England weather to any out-of-towner we meet. Twain really did say “If you don’t like the weather in New England, just wait a few minutes,” and since 1932 every meteorological anomaly that has impacted our region has been faithfully observed, recorded, and shared by the staff of the Mount Washington Observatory. Here’s a look at my 2014 visit.

The Mount Washington Observatory | New England’s Weather Station

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

Located at the summit of the tallest peak in the northeastern United States, the Mount Washington Observatory is a private, non-profit organization that maintains a 24-hour watch of the “World’s Worst Weather” 365 days per year. This rugged little building that looks like an unpainted lighthouse is closed to the public, but I recently had the privilege of touring the facility and spending the night to see what it’s like to live and work as a weather observer.

The Observatory has a staff of nine weather observers and interns who are divided into two teams. These two teams work in alternating seven-day shifts at the summit. When one team works, the other team rests and reconnects with loved ones.

In the summer, the observer teams are shuttled to the summit by van, but once the snow starts to accumulate, a more aggressive form of transportation is required. The MWOBS snowcat is a beast of a vehicle that carries up to 12 passengers, their gear, and a week’s supply of observatory food in as little as two hours depending on the weather.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

Observer shift changes happen every Wednesday and the routine never varies. Upon arrival at the summit, the crew waits for the driver to secure the snowcat and open the back door. The crew then forms a human chain to unload the arriving crew’s gear and supplies and load the departing crew’s gear and trash.

At 6,288 feet, Mount Washington is a molehill compared to other famous mountains like Everest (29,029 feet) and K2 (28,251 feet) yet New England’s tallest peak is where the fastest human-observed wind speed in history was recorded at 231mph on April 12, 1934.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

During my visit, I experienced sustained 82mph winds that made the simple act of walking a real challenge. Interestingly enough, the SECOND fastest wind ever recorded at the observatory is 182mph in 1980, which makes the 231mph blast of 1934 even more remarkable.

How is it possible for such extreme weather to occur less than four hours from Boston? Since the observatory is located at the highest point in the northeastern United States, there’s nothing to block the path of the three major storm systems that converge at Mount Washington. This perfect storm of factors results in an average January temperature of 5 degrees Fahrenheit, 45 mile per hour winds and 200 feet of visibility due to fog and blowing snow.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

Each hour, regardless of weather conditions, an observer ventures out from the protection of the observatory to manually gather precipitation collection cans and ensure all instruments are free of damaging ice and snow. Several of these instruments are located at the highest point of the observation tower that’s accessed by climbing two profoundly narrow flights of stairs.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

Here is where rime ice is unceremoniously dispatched with a crowbar and brute force; not exactly what these highly-educated professionals went to school for, but it’s a vital part of their hourly routine.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of the Mount Washington Observatory

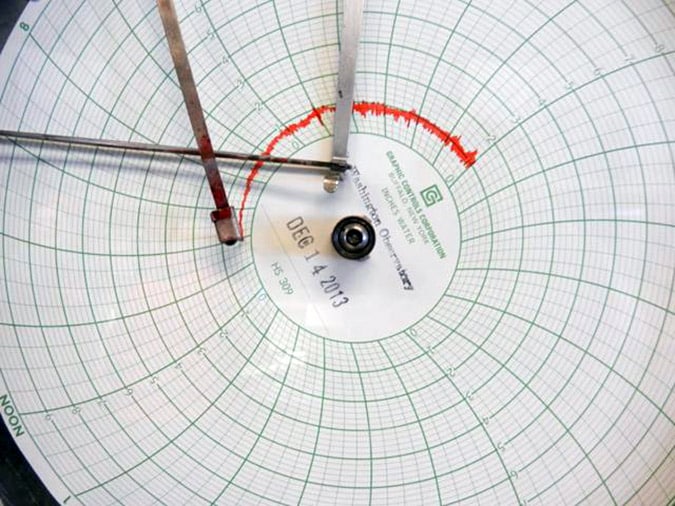

One of the most interesting instruments at the observatory is the Hays device, which logs real-time wind activity for a 24-hour period. On the day I left the summit, conditions were surprisingly calm and the print-out looked like this:

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

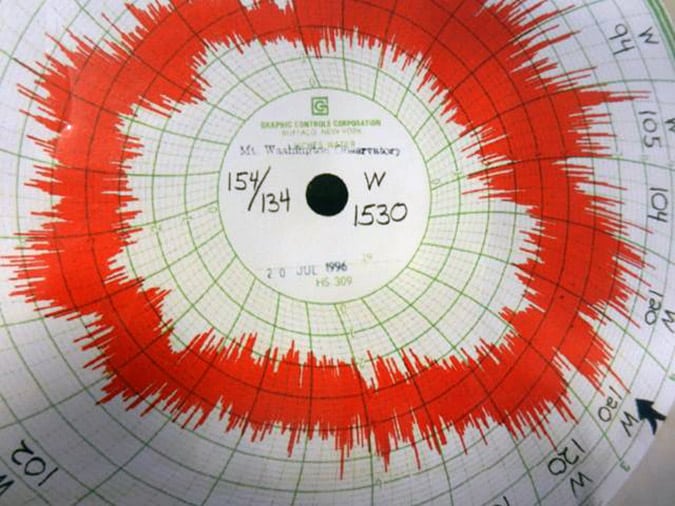

In contrast to the serene image above, take a look at the windiest 24-hour period in the history of the observatory:

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

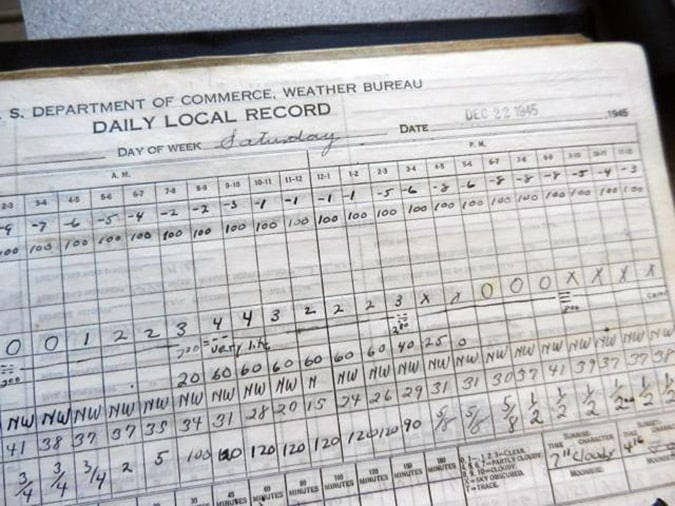

During my visit, I was most impressed with a special project that’s currently underway at the observatory. Before computers, all weather observations were meticulously recorded by hand into logbooks.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

When they are not assisting with data collection, the observatory’s interns are transferring those handwritten journals into digital records that will be a real asset for research.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

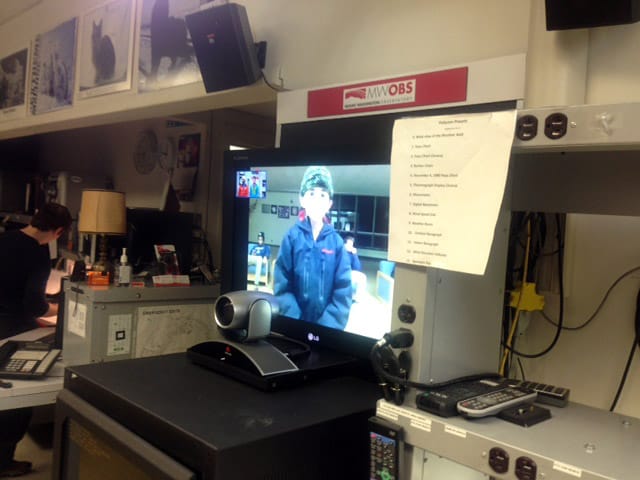

In addition to their observation and recording duties, the observers provide morning weather reports for several area radio stations. Observers also share their passion for meteorology with future generations by conducting interactive Web broadcasts to students all around the world.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

When the observers are off-duty, they retreat to the living quarters at the ground floor of the observatory. Here, they are free to relax on one of the comfy couches, play one of their favorite board games, watch a movie or grab something to eat. All meals and snacks are prepared by a pair of volunteer cooks who arrive and depart the summit with every shift change. These dedicated people sign up months in advance for seven days of cooking, light cleaning, and motherly/fatherly caretaking that help the observers feel at home.

Additional comfort to the staff is provided by the only year-round resident of the observatory, Marty the Cat, whose playful ways and demands for attention make seven days away from family and furry loved ones easier to deal with.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

During my 24-hour stay at the Mount Washington Observatory, I experienced winter fury that nearly knocked me over as well as profound serenity under a cloudless blue sky that took my breath away. I had the good fortune of being there on one of the few days each year with no fog enabling me to see for hundreds of miles in every direction.

Photo Credit : Jim Darroch

I left with a greater appreciation for the mountain itself as well as newfound respect and admiration for the men and women who work there. The Mount Washington Observatory operates almost entirely on donations from members and corporate sponsors. I can’t begin to imagine how much it costs to heat the facility and power the wall of technology that monitors the World’s Worst Weather, but it’s a uniquely New England story that needs to be told.

If you’re interested in supporting the work of the Mount Washington Observatory, volunteering your time, or having the same overnight experience I had as part of an Edu Trip, you’ll find everything you need to know at mountwashington.org.

This post was first published in 2014 and has been updated.