The Essence of Appledore

Eating what you gather on an island can change how you look at food—and even life itself.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

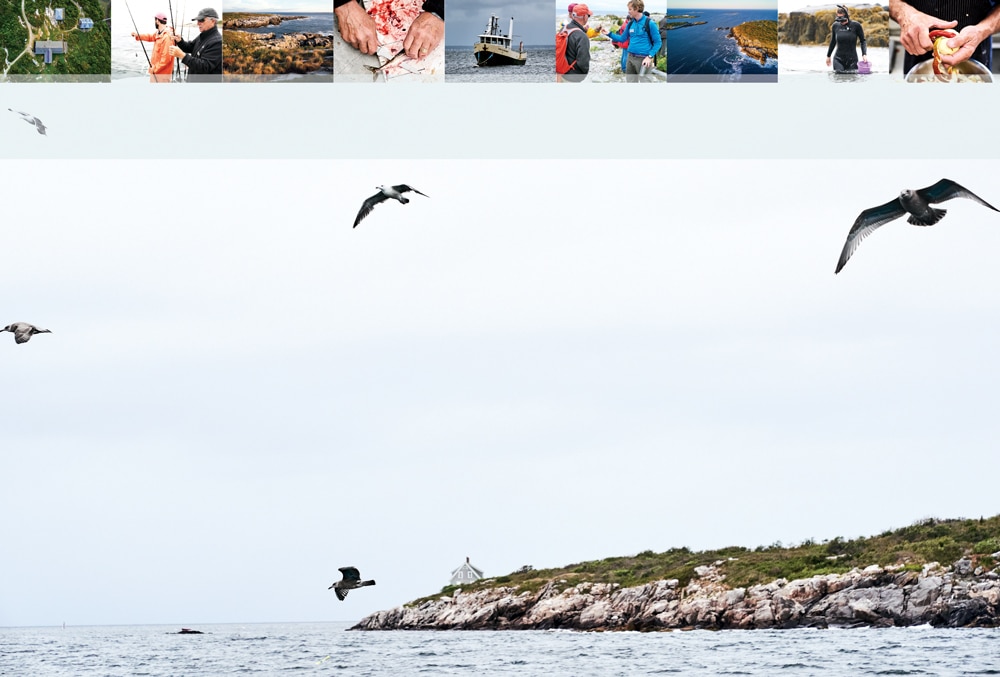

Appledore Island is a glacier-raked lump of granite six miles off the New Hampshire coast. In shape, color, and smell, it resembles a giant oyster shell. When Sam Hayward, who would go on to become one of Maine’s most celebrated chefs, first saw Appledore from the deck of a shrimper in the spring of 1974, he wondered if he’d made a terrible mistake.

A luxuriantly mustachioed 20-something with no culinary experience, he’d talked his way into a position as the cook for the new Shoals Marine Laboratory, jointly run by the University of New Hampshire and Cornell University, which was still under construction on Appledore, as a way of getting himself out of Ithaca, New York. He’d visited the Maine coast and fallen in love with it, but Appledore surprised him. “It wasn’t what I’d imagined,” he recalls. “This was not another Maine porcupine island, spruce-covered and grassy. It was peaty and more or less barren.”

In that assessment, Sam was following a long line of people who had arrived at the Isles of Shoals—a handful of tiny islands shared by New Hampshire and Maine, of which Appledore is the largest—and failed to see the charm. Few trees, thin soil, angry gulls, zero comfort. On a snotty day, wind spitting sleet across the water, they can be bleakness itself. In terms of arability, or natural resources, or strategic value as a port, or any of the usual ways we measure value, the Isles of Shoals are pretty worthless.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

But what Sam did not know on that day in 1974 was that he was about to follow another tradition, one of people—from the early fishermen who discovered teeming shoals of cod (and named the islands for them), to the impressionist painters dazzled by a kind of light they’d never seen, to the generations of biologists who found in the isolation a perfect living lab—who’d come to see abundant riches in these rocks.

First, he had to get ashore. The only person living on the island was the engineer, who was building the marine lab literally from the ground up. He hadn’t gotten to the dock yet. The boat on which Sam had hitched a ride out of Kittery pulled as close as it could to the seaweed-slicked rocks, and the pilot told Sam to jump. “I was wearing smooth-bottomed leather moccasins made for me at the local hippie haberdashery,” he remembers. “The waves were pounding the rocks.” Sam jumped. “Boom, down I went.”

Soaked and humiliated, Sam wondered if he was in over his head—a feeling that only grew as he realized the lab facilities were mostly theoretical. The plumbing barely worked, the kitchen was a shell, and they had to dig decades of muskrat poop out of the only well.

But he stuck with it. The rest of the staff arrived, and together they launched a uniquely hands-on marine lab. “There was a pioneering spirit,” he says. “In that freewheeling, creative environment, almost anything was welcome.” Cooking meals for 100 students and staff with limited facilities, he got his culinary boot camp. But he also learned to see food in a way few people did in 1974.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

“Weird fish was the air you breathed out here,” Sam says. “The fishing boats out of Gloucester and New Bedford passed right by the island. We got the reputation for being the crazy guys who’d buy anything they dragged up off the bottom. We’d hand out fileting knives to the students, and in the name of gross morphology they’d prepare dinner service.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Nothing is hidden on Appledore. Whether you’re a marine bio student or a young chef, you get to see all the pieces of the puzzle. For Sam, it was a crystallizing moment. “We’d slit open the stomachs of these huge cod and what would spill out but hundreds of one-inch baby lobsters. I started realizing that cod and lobster are connected, that when you’re eating a cod you’re not just eating a cod, you’re eating everything that the cod has eaten. I started wondering about the whole ecosystem of the Gulf of Maine. Where are the baby lobsters hiding? Where are the kelp forests that the baby cod hide in? Are the urchins so sweet because they’re eating the sugar kelp? And I was fortunate to be surrounded by scientists who could answer my questions. Those are the things that stayed with me and continue to inform my cooking.”

Sam cooked for the Shoals Marine Laboratory through the 1976 season, then embarked on a series of restaurant adventures that would culminate in his famed Portland eatery, Fore Street. But he never forgot Appledore.

Fast-forward 40 years. I’ve come to Appledore with Sam Hayward and two dozen other brave souls for “Take a Bite Out of Appledore,” a weekend of foraging and fieldwork dreamed up by Portsmouth chef Evan Mallett and the marine lab’s executive director, Jenn Seavey. Meet the ecosystem, then eat it.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Seemed like a good idea at the time, but I’m walking through the scrub to join Evan on an intertidal hunt for crabs and periwinkles, and I’m just not seeing it. The day is a gray drizzle. Gulls scream at me. A lonely buoy clangs in the fog. Sea meets shore in a frothy mess of coves and spits. Abundance is not the first word to come to mind.

I’m definitely not seeing whatever Childe Hassam saw. America’s leading impressionist, Hassam first came to Appledore in the 1880s at the invitation of poet and local resident Celia Thaxter, whose summer salons drew a who’s who of artists and writers. Cod fishing had collapsed on the Shoals long before, but they’d been reimagined as a place for Victorians to escape the summer heat. Grand hotels appeared on Appledore and Star islands, while Smuttynose hosted the Mid-Ocean House of Entertainment.

Hassam had already become famous for his street scenes of Paris and New York, but those paintings feel programmed, as if he had a buyer in mind. Appledore broke him open. As I walked, it wasn’t hard to see why. Less than a mile from end to end, with few trees to get in the way, Appledore is a funhouse of vistas. Hassam painted them all, more than 250 paintings, returning to the island almost every summer from 1886 to 1916.

Jenn Seavey, whose ancestors came to the Shoals in the very beginning and founded Seavey Island, a stone’s throw from Appledore, makes a game of matching Hassam paintings to their exact vistas. He was faithful to every rock.

“But he made up the colors!” I protest. Pastels dance out of Hassam’s granite. His seas swell with purple. The island ripples with sentient energy. It’s as if he transplanted Appledore to the Caribbean—a dreamy illusion.

“No,” Jenn insists. “It’s real. You’ll see.”

Down at the tide pool, Evan and a few others are suiting up for foraging. A cold rain pelts us as we strap on snorkel gear, already starting to shiver. Evan, who has a reputation as not only New England’s best wild-ingredients chef but also the one least likely to have a fallback plan, needs crabs and oysters and periwinkles for dinner, and there’s only one way he’s going to get them.

“Look for really small crabs,” he advises us as he wades into the water. “The smaller the better.” And with that he plunges into the four-foot-deep pool.

Evan grew up playing on the beach in Rye, New Hampshire, gazing out at the Isles of Shoals. “They’re my unicorn,” he tells me. “On days when it’s too foggy to see the islands, if the lighting is right they actually cast a mirage of themselves that you can see from anywhere on the New Hampshire shoreline. That’s part of my mystical association with the islands. I could go to the beach on a foggy day and see an image of the Isles of Shoals flickering on the horizon.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Having failed to squeeze myself into any of the lab’s wetsuits—apparently marine science students are built like whippets—I pull on my mask and snorkel and trudge into water so cold my breath shudders. The bottom of the pool is covered with periwinkles and tiny crabs scuttling across rust-colored cobble. They scatter like cockroaches as I glide over. After five minutes I have just two crabs in my net sack and I’m shaking wildly. This does not bode well for dinner.

I switch to periwinkles, and then I find a nice patch of oysters. My bag starts to feel heavier. I’m also numb, which is an improvement. I start to anticipate the crabs’ movements, catch a few, and lose myself in the metallic light of the pool.

When I finally raise my head from the water, lips so cold I can’t talk, the world feels different. People splash out of the water with their treasure, shaking and laughing. We’ve got the raw stuff of Appledore, and we’re ready to make something out of it.

As we head back to the lab’s kitchen, Evan confesses that part of him wishes cooking could always be like this. “On an island, there’s no time for trial and error. You find an ingredient, you gotta use it. You just ask yourself, How am I going to put this in front of people in a way that’s delicious and that helps tell the story of this place? To me, the most important ingredient in a chef is the ability to adapt on the fly. Culinary school teaches you to try to control everything, but your greatest asset is what you do when those systems break down.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Evan tells me that when he proposed “Take a Bite Out of Appledore” to Sam, “I thought it was going to be a difficult sales pitch. But he responded with a resounding yes. There’s a risk dragging a legendary guy into something that doesn’t even have a definition yet.” He flashes a wild grin, teeth chattering, as rain sluices off the bridge of his nose. “It’s a darn good thing it’s going so well!”

I won’t lie. We had a lot of help with dinner. It takes a village of marine biologists and chefs and fishermen to make a spectacular dinner on a lonely island. Sam led a fishing expedition in a marine lab boat that came back with buckets of mackerel. We scored lobster from the last Isles of Shoals lobsterman, and cod and cusk from Tim Rider, the last commercial rod-and-reel fisherman in the Northeast, who hand-delivers his catch to the lab just as the boats used to do for Sam 40 years ago.

Cam Heins, the current Shoals chef, was foraging like a madman before our arrival and is able to augment our meager take. Straight out of culinary school, Cam is the Sam of 2018. This is his first real gig. He’d worked one summer at Evan Mallett’s Black Trumpet and got the job on Evan’s recommendation, for which he was incredibly grateful. “I couldn’t have asked for a better opportunity,” Cam tells me when I join him for a last-minute berry run. “I can order whatever I want. I can make whatever I want. I have full creativity.”

As we walk back toward the kitchen with baskets of serviceberries and chokecherries, he still seems a little stunned at his good fortune. “I’ve known Evan since I was pretty young,” he says. “I’ve always been inspired by what he does. You see five new ingredients every time you walk into the Black Trumpet. He’s always been my mentor. So having the opportunity to work with him and his mentor is really amazing.”

Like Sam years earlier, Cam took Appledore’s lessons to heart. “You’re not just buying an ingredient that’s being delivered to your restaurant. You’re going out and looking for it, and picking it, and processing it, and deciding what it’s going with. It just adds so much more heart to the dish.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Cam slips away to the kitchen to start infusing some of that heart into things. When we gather for the meal a few hours later, it’s there. We sip elderberry cordials and beer made with hops from Celia Thaxter’s garden while nibbling on the periwinkles and crabs, fried crisp as potato chips. We eat grilled mackerel and raw oysters spiked with sea lettuce. There’s a salad of red goosefoot, calendula, and peppery wild radish pods as vibrant as any Childe Hassam watercolor. Sam makes a shaved “apple snow” meringue from gnarled apples growing near the marine lab, and Cam makes cake rolls with swirls of blackberry and serviceberry. There’s lavender ice cream, courtesy of Celia’s garden, and chokecherry syrup on the side. We toast the chefs and the fishermen and the artists who long ago set a tone of paying attention to the world around them—a lineage that leads straight to the Shoals Marine Laboratory today.

After the meal, Sam and I duck out so he can show me his favorite spot on the island. It goes by the unromantic name of Transect 18—this is a science lab, after all—but it’s a stirring sweep of rock on the exposed east side with clear views across the Atlantic. Sam says he’d come out here to watch the sun rise or to trace the constellations at night. To him, it’s the essence of Appledore. “This island is experiential,” he says, “it’s direct, it’s transcendent, it’s beautiful. It’s wonder and mystery and love of the environment—everything that’s become important to me in the intervening decades.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

It was here that he saw his path unfolding. “I started asking myself, How can I experience that interconnectedness? How can I bring diners into that same sense of mystery and awe, which food hasn’t had in the era of industrial agriculture? It’s a way of connecting with the world that never occurred to me until I got to this island, and it has done nothing but expand and grow since that time. I know that sounds quasi-mystical, but that’s what cooking has been for me.”

I nod in understanding, and for a while we silently watch the waves churning against the rock as clouds tumble overhead. Suddenly, a ray of sun lights the foaming sea in tropical streaks, and we are in a Childe Hassam masterpiece. I turn and gaze across the island at the lichen-splotched rocks and dancing goldenrod, and I stand corrected. Hassam didn’t make up a thing. He discovered in Appledore’s wild light and raw experience some fleeting yet irreducible truths, and he keenly mined them for 30 years.

And in a way, I guess, we’ve all come here for that clarity. The artists, the scientists, the chefs, the hungry wanderers. Appledore had plenty to give, if you did what we’re doing now. Stand on the edge. Shiver a little. Keep looking. And wait for the light to break just right.

This year’s “Take a Bite Out of Appledore” event will be held 9/1/18–9/3/18. For details, go to shoalsmarinelaboratory.org.

A stunning portrait of a deserving subject. Thank you… I can nearly taste the periwinkles and see the pastel hues of Hassam’s creation.

I still remember with awe the 11-course dinner Sam Hayward prepared for the 1976 dedication of a Shoals Lab building. His enthusiasm for food was great then and has only grown greater.

Oh wow that menu sounds so delicious and right out of my Gramma Gray’s kitchen when I was a kid growing up in Rye. I woke up every morning staring off at the Shoals too! I will be back!