Striding Into Boston Marathon History with Kathrine Switzer

On the eve of the 126th Boston Marathon, history-making runner Kathrine Switzer looks back on how far the race — and the sports world — has come.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Kimberly Glyder

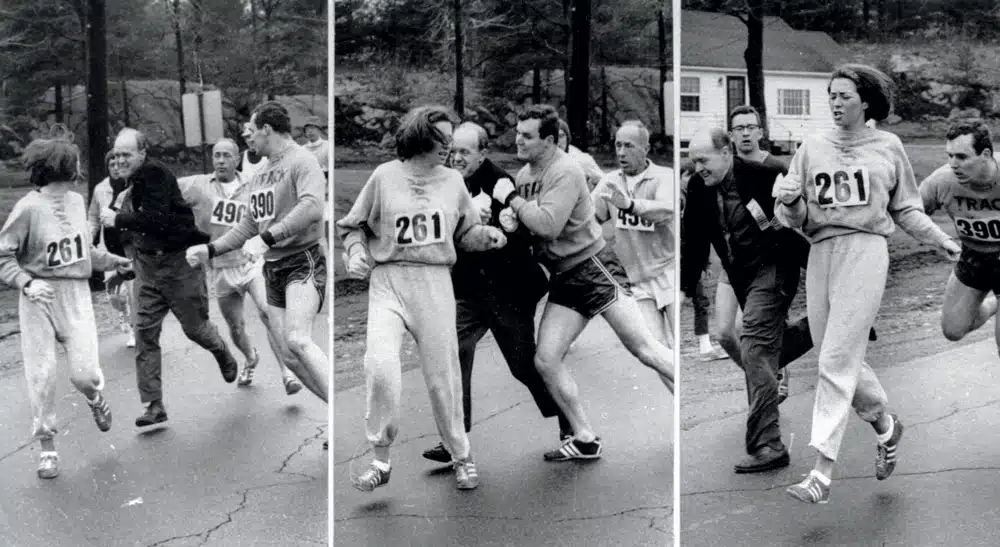

It’s one of the most famous running photos in history, and it doesn’t show a champion crossing a finish line or a brokenhearted runner-up. It’s the indelible image of a 63-year-old man trying to push a 20-year-old woman out of the Boston Marathon, contending (though gender wasn’t mentioned in the rules) that women weren’t allowed.

The runner, Kathrine Switzer, eluded cantankerous race official Jock Semple that day in 1967 and finished the race; she’d signed up under the name “K.V. Switzer” and—in the cold and snowy weather—worn a baggy sweatsuit that kept her from drawing attention at the starting line. That made her the first woman to officially run Boston, the number 261 safety-pinned to her sweats.

The incident helped pave the way for formal acceptance of women in the race in 1972, the first time women were invited to participate in what had been a male-only sports event. Switzer was back, among eight women (she came in third) in that epochal year for women athletes, when Title IX would also pass. Then, as organizer of the Avon Running Global Women’s Circuit, she spread the women’s running gospel worldwide. By 1984, the Olympics had added a women’s marathon, which Switzer also helped to push for, and for which she provided color commentary.

Photo Credit : Harry Trask (Boston Traveler/Boston Herald)

Switzer won the New York City Marathon in 1974, in 3:07:29. But she was just as intent on breaking three hours in a marathon as she was on shattering barriers for women, and she did that the next year in Boston, with a personal-best time of 2:51:37. By then, it was only good for second.

Today, slightly more women than men participate in running events, according to the International Association of Athletics Federations, and the defending women’s marathon record has fallen to 2:14:04, set by Brigid Kosgei at the Chicago Marathon in 2019.

Switzer has started a nonprofit, 261 Fearless, that seeks to empower women through running. “It results in self-esteem, in confidence, in fearlessness,” she says. “And once you feel empowered, you can leave a bad relationship, you can ask for a raise, because you have the strength to do it.”

In 2017, the 50th anniversary of the Jock Semple incident, Switzer ran the Boston Marathon at 70, finishing in 4:44:31—only about 20 minutes slower than she had in 1967. Running with her were 125 women from 261 Fearless.

After the race, the Boston Athletic Association retired her number in her honor.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jon Marcus: People forget how high the barriers were for women in sports when you were in high school and college.

Kathrine Switzer: I was very, very lucky. Our high school [in Virginia] actually had girls’ sports. It wasn’t just cheerleading, although cheerleading was the ideal. We had field hockey, girls’ basketball, and girls’ softball, and that was really quite amazing. Other girls in my generation had almost nothing. Even at my high school, what was difficult was that, in general, the girls’ sports were laughed at by both boys and girls. If you participated in sports, you were considered a tomboy. So everybody wanted to be a cheerleader.

J.M.: Including you.

K.S.: [Laughs.] I told my father that I wanted to be a cheerleader. And my father said, “No, you don’t. Cheerleaders cheer for other people. You want people to cheer for you.” He said, “Your school has something called field hockey, and I don’t know what that is but I know the girls run. And I know you can run. I know you can run a mile a day.” He measured off the yard, and that’s how I started running. When I started at the high school that autumn, I tried out for the field hockey team. And there were all these older kids, but I had run a mile a day and I felt empowered by it. It was that mile a day that changed my life.

When I talk to my other friends who were in that generation, they had nothing but cheerleading. They didn’t have a mom or dad who encouraged them to run.

J.M.: People thought women couldn’t physically handle long distances, or it would affect their ability to have children.

K.S.: Oh, definitely. First of all, it is hard. It is long. And women who hadn’t been running, they would go out and run around the block and they would be exhausted. Everyone who’s just starting out runs the first 100 yards and they go as fast as they can and then they feel terrible. My father told me, “Just run at a pace that’s comfortable.”

A lot of my girlfriends in the neighborhood would see me out running. They would whisper to me that I was going to get big legs, I was going to turn into a man, I might start growing hair on my chest, but for sure I wasn’t going to be able to have children. I didn’t believe it for two reasons: I didn’t believe it because my dad encouraged me to do it, and if he wasn’t afraid of it, why should I be afraid of it? And the other reason was that I felt so empowered, I didn’t care what people said.

J.M.: Who were your role models? Were there any at that time, for women athletes?

K.S.: Not really. [Olympic sprinter] Wilma Rudolph wasn’t really a role model for me because I wasn’t a sprinter. I couldn’t go fast. My role model was actually Margot Fonteyn, who was a ballerina. As a girl I read an article about her, and she trained like a Trojan. I thought I could do that with the marathon, if you want to know the truth. It’s because of her that I always wore girly-girl outfits. I wanted to refute that image that women athletes were masculine. I wore a nice-looking outfit for ’67, but it turned out to be freezing cold. So I had to wear my crummy old sweatsuit over it. That’s probably why they didn’t stop me from starting; if it had been a warm day in Boston, I might never have been able to run. But I was disappointed, because I had really wanted to look nice. Afterward I would paint the house in that sweatsuit.

J.M.: You’ve said that in high school you’d never heard of anyone running farther than three miles. Why choose distance running?

K.S.: I couldn’t go very fast, but I could go forever. And the longer I ran, the better I felt. I felt quite triumphant and fearless, really. I was at Lynchburg College for two years after high school and it was at Lynchburg that I got recruited onto the men’s track team. The coach needed somebody to run the mile. It wasn’t against the rules in that conference [for a woman to run], but it created quite a sensation. I would have preferred to have run two miles, because in the mile I was always last. I liked going far.

J.M.: The idea of running Boston almost seemed to stalk you.

K.S.: I transferred to Syracuse University, and they didn’t have any girls’ sports at all. So I ran as an unofficial member of the men’s track team. One of the guys on the team ran the Boston Marathon, and I was also writing for the college newspaper and I wrote an article about him. And I asked, “Did any women run?” And he said yes. [The woman was Bobbi Gibb Bingay, who ran unregistered in 1966.] And I asked, “What time did she run?” And he said about a 3:20. And I said, “What did you run?” And he said about a 3:40. And I said, “You let a girl beat you?”

We had this volunteer coach [Arnie Briggs], and he had run 15 Boston Marathons. And he felt sorry for me because I kept getting lost, so he would run with me and always tell me another Boston Marathon story. It was marvelous to have a really experienced marathoner be my running buddy. So my interest in Boston was really getting fired up. When I said I wanted to run it, he said a woman couldn’t do it. He said, “If any woman could, you could, but I don’t think you can do it.” So that was always the goal. I was going to show him.

J.M.: You entered Boston in 1967 with Briggs and some of your Syracuse teammates, leading to the famous incident in which Jock Semple tried to push you off the course. That moment took on a life of its own. How would you like it remembered?

K.S.: You couldn’t have staged that if you were Cecil B. DeMille. The combination of the weather suddenly being so ridiculously bad, officials trying to get the race started on time, everybody running around in circles trying to stay warm. I just wanted to lay low and start the marathon. And then the press truck came up beside us. And it all kind of came together at that moment. Who would have imagined that Jock Semple would have been enough of a bozo to jump off the bus in front of the press truck and come running up behind me, in front of all those cameras?

I prefer to think of it as a positive moment, of the moment things began to change. As bad as it was for me, in a way it was the best thing that happened in my life. It changed women’s running forever. It was the spark that started the women’s running revolution.

J.M.: Half the world thought you shouldn’t have run, and the other half criticized you for not running faster.

K.S.: I received fan mail, and I received hate mail. Half the people who heard about it thought I totally deserved it. What was I thinking? Why was I such an uppity person? Why couldn’t I leave the men alone? I just threw away the hate mail. Why would I want to read hate mail? In the fan mail, there were people who said, “We cut your picture out of the paper and we put it on the mantel.” So I just focused on the positive. I didn’t have a problem being in the spotlight. I always believed so strongly in running.

J.M.: Was there a degree to which that incident drove you to keep running—not just that day but afterward?

K.S.: I would have run for the rest of my life. There’s no question. It was just too important to me. I couldn’t live without the sense of empowerment and even religion that running gave me. It’s a transformational experience. But after that day, I really needed to take responsibility for it. My mom and dad always said, when you start something, you’d better be sure that you can finish it. I’ve always felt enormous responsibility to that moment.

J.M.: A lot of people would have harbored anger.

K.S.: Was I angry at Jock Semple? Yes—up until Heartbreak Hill, I was really angry. But once you get past those hills, you’re on fumes. And you can’t stay angry any more. You have to focus on the race. The only thing I could do was keep on running and show women they could do this. It’s like a ball of snow. It’s going to grow fast. And that’s exactly what happened.

J.M.: You have written that some of the people who seemed to resent what you were doing were other women. What was that about?

K.S.: That was the really hard part. The only drivers who tried to run my coach and me off the road [in Syracuse] were other women. And I said to him, “Why is it always a woman?” And he said, “Because you’re powerful.” Women were very fearful of women who exhibited physical power and worried that we were stepping into a male domain. They had a sense of fear. Sweat was really inappropriate. You needed to be dainty and clean and perfume-y. Look around the world—this stuff still exists.

J.M.: Conversely, male runners were supportive. A lot of them encouraged you when they saw you along the marathon course.

K.S.: I found that very interesting. Here’s a good example: At Syracuse University the guys on the cross-country team were very welcoming. When I would train with Arnie, older masters runners would come and run with us. And they never thought of it as they were men and I was a woman. We were just running together. Running to me is the best example of inclusion and diversity and equality and respect. If the guys in the marathon were full of catcalls and innuendo and spit at me, as they often did in other sports with women, it would have been very hard. On the contrary, they would say, “I wish my wife would run,” “I wish my girlfriend would run.” They believed that women should run. And why not? I’ve always said they were the original sensitive new-age guys. Runners are different. They have a sense of fairness.

J.M.: So then in 1972 women were finally officially allowed to run the marathon, but they had to have a separate starting line and be scored apart from the men and meet a qualifying time of 3:30.

K.S.: We had pushed the door open a crack. Let’s be happy with any gains we have. Because once you make that gain, you can make another gain. Jock Semple was the one who said, “If these women are going to run in my race, they’re going to meet the men’s qualifying time,” because he was going to protect his race. After that race he said, “Well, they actually ran pretty well.” None of us ran very well that day. But we still prevailed and the media regarded us for the first time as athletes. That was the big thing. They covered us and it was huge news.

J.M.: As much as your running Boston broke barriers for women, you also seemed intent on the personal goal of breaking three hours. You wanted to be known as an athlete and not just the woman in that photo.

K.S.: My intention was not originally political. After I got attacked by Jock, it became political, because I didn’t have any choice. Then I had a lot of homework to do. Everybody dismissed me and said I ran it in [the comparatively slow time of] four hours and 20 minutes. Jock Semple said I could have walked it that fast. And I wanted them to shut up. I also became physiologically curious. Could an ordinary runner like me become a faster runner? I trained my brains out. I was lucky I didn’t get injured. And I ran well.

J.M.: Also in 1972, Title IX passed, and after that the Olympics added a women’s marathon. You’ve said that having a women’s Olympic marathon was as important as American women getting the right to vote. Why is that?

K.S.: Not just because it took place, but because it acknowledged women’s equality in the longest running event in the Olympic Games. The vote was about women’s intellectual acceptance. The Olympics were about our physical acceptance. It changed the landscape—one part of the landscape, anyway.

J.M.: What was it like to watch that first women’s Olympic marathon, where you were a commentator for ABC?

K.S.: I was trying very hard to be professional and not emotional. I thought nobody’s going to understand the importance of the moment until the first woman comes through the tunnel and into the Olympic stadium [it would be Maine’s own Joan Benoit]. And that’s exactly what happened. I was working with Al Michaels and he said, “When she comes into the stadium, say nothing. Say nothing. Let the crowd take it.” So we did.

But then when [Swiss marathoner Gabriele] Andersen-Schiess came in reeling [from heat exhaustion], the thoughts came screaming back into my mind—they’re going to pull the event because they’ll think women can’t handle the pressure. Fortunately, people regarded it as heroic instead of awful and desperate. That was a major shift in people’s thinking. People were brought to tears by seeing a woman so determined to finish.

J.M.: You went on to organize the Avon Running Global Women’s Circuit, putting on events around the world. I’m guessing you got the same kind of pushback doing that, if not worse. Do you remember any in particular?

K.S.: I had to go through it again and again. Germany, France, Italy, Southeast Asia. Japan was one of the worse. They just couldn’t accept having a race for women, but we were going to do it anyway. They said, “It’s very dangerous for women to run. You can only have a 5K and no one under 18 can run—it might injure them.” Well, 1,000 women showed up in Japan. Women for the first time in Japan had something that was theirs. It was such a huge success; they imitated it and went off and got another sponsor. I got angry with that, but then I got over it and said who cares. And look at who the successful runners are now from Japan: It’s the women, not the men.

J.M.: Not just in Japan, but worldwide, women today outnumber men in running events.

K.S.: The happiest day of my life was when I ran again in 2017, my 50th anniversary [of the Jock Semple incident]. That was awesome. I had been the only woman with a bib back then. And when I looked around, I was surrounded by 13,500 women with bib numbers, all officially qualified. And everyone on the street was cheering or holding up their little girls and saying thank you. The other phenomenal thing was that waiting at the finish line was Joann Flaminio. She was the first woman president in 130 years of the Boston Athletic Association.

J.M.: Do you worry that, after 50 years, younger generations might forget how hard it was to get these things they take for granted?

K.S.: Running is too visceral for that. They feel it so acutely. It’s such an important part of their lives. I say to them, “Pass it on.” They’ll show their kids, both boys and girls, how important it is to be active. I think they’re getting all of that, and grateful for it. And I am full of gratitude that they are grateful.