Spear of the Realm | First Light

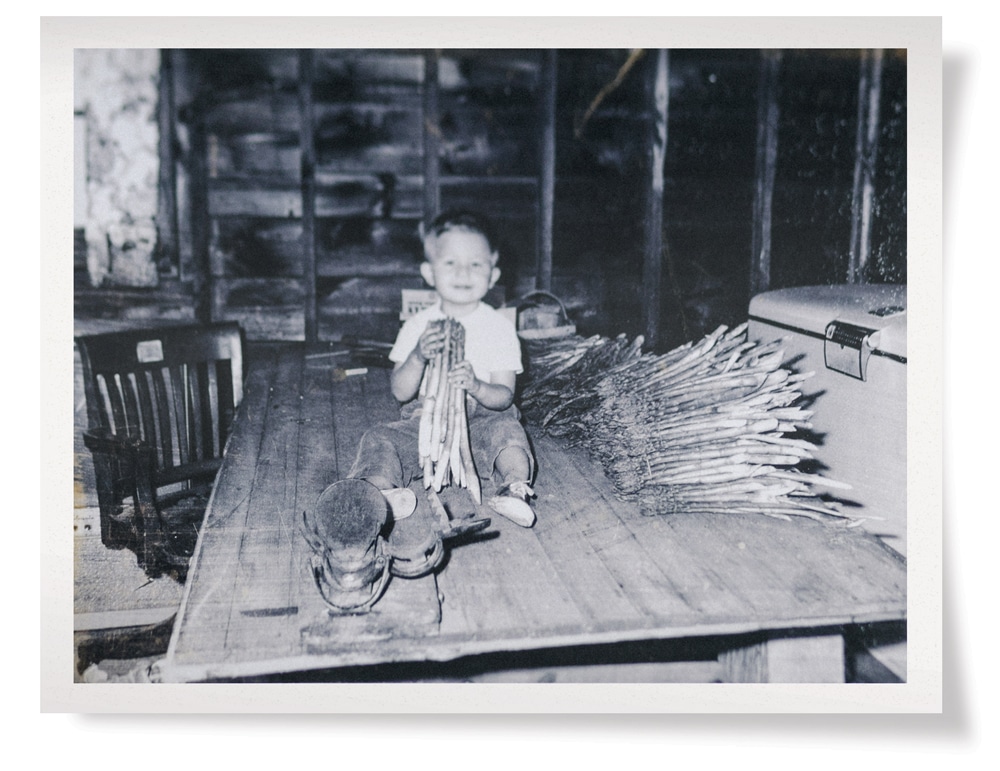

The rough wooden farmhouse table in the black-and-white photograph holds a pyramid of asparagus. It also holds a softly smiling toddler just a little bit taller than the bunch of stalks in his hands. That’s Dan Smiarowski, who today at age 56 uses the photo to answer the frequent question of how long has he […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanThe rough wooden farmhouse table in the black-and-white photograph holds a pyramid of asparagus. It also holds a softly smiling toddler just a little bit taller than the bunch of stalks in his hands.

That’s Dan Smiarowski, who today at age 56 uses the photo to answer the frequent question of how long has he been growing asparagus. “I just post this picture, saying, ‘This long.’”

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

The photo is a bit fuzzy but the picture is clear: Asparagus is a life’s work. And in the Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts, often called the asparagus capital of the world, it also can be a legacy. Dan’s surname is locally synonymous with the first and most revered of spring sprouts, as the extended Smiarowski family runs four separate farms and a large seasonal store in an area that since the 1930s has sprouted both Asparagus officinalis and asparagus family dynasties.

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

Hadley, Hatfield, and Whately are among the towns making the most of the perfect-asparagus combination of temperate spring weather and the ultra-rich ancient bed of glacial Lake Hitchcock, which once stretched 215 miles from St. Johnsbury, Vermont, to Rocky Hill, Connecticut. Its slow recession to what is now the Connecticut River created what Dan calls “some of the best soil not only in the country, but in the world”—said as all fact, no boast.

The distinctively sweet and grassy-tasting asparagus grown here manages to be both meaty and melt-in-the-mouth. Often called Hadley Grass—for both one of the well-known growing towns and the plant’s folk name of sparrow grass—it’s coveted by locals and far-flung diners alike, having been served at the annual spring feast of Queen Elizabeth II.

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

The scourge of Fusarium, a soil-borne fungus, obliterated the valley’s crop in the ’70s, throwing farmers’ focus onto corn, potatoes, and onions. But disease-resistant varieties of asparagus, including the currently prolific Jersey Supreme and the popular Millennium, have meant the crop’s welcome return here, including at Dan and Penny Smiarowski’s D.A. Smiarowski Farms in Sunderland and Montague.

The couple spend this spring morning as they have almost every other one in their 27-year marriage, bunching and trimming freshly picked asparagus at folding tables in the double garage of their neat tan Cape in Sunderland. Crates of 24 bunches each are trucked daily to local and regional vendors, the farthest 100 miles away in the Boston area and southern New Hampshire. Two or three customers alone take up to two weekly orders of between 10 and 12 crates throughout the harvest season of early May to late June—think of it as asparagus farmers’ version of accountants’ tax season.

For these months, the garage is command central amid the few square miles of Dan’s asparagus-entwined life. The main fields are a three-mile truck ride north into Montague, past a sign for Smiarowski Road and past the former homestead of Dan’s aunt and uncle, Stanley and Betty Smiarowski, to the field across from the farmhouse where young Dan was photographed long ago. All around him now, 125 acres of brown soil are punctuated by spears of vibrant-green Jersey Supreme asparagus, poking skyward like surprises.

A tractor rolls past land first planted by Dan’s Polish-immigrant grandfather, Alexander, then by Dan’s dad, the late Eddie Smiarowski, who ran a dairy and grew pickling cukes, sweet corn, and, of course, asparagus. Along this same stretch of road, Eddie’s late brother, Stanley, also grew the crop.

“I had my father, and I had my Uncle Stanley,” Dan says as he stands on land his uncle knew inch by inch. “He was my second father.”

The fields along this road are his favorite. His late mother, Monica, worked here alongside her son, who would rise at 4:45 to pick before school.

High school and college kids have always picked asparagus throughout the valley. Dan planted additional fields 20 years ago, then needed daytime hands for the job of scanning the rows and bending to cut spears at ground level with a simple knife. Seven to 12 migrant workers, many from Guatemala, now do his picking. Garbed in sweatshirts, long pants, and gloves on a warm May afternoon, they chat with Dan at the edge of the field during one of several trips he makes to check on their safety and to collect the latest harvest awaiting in black plastic totes dotting the landscape.

Friendships have grown over the years, texts keeping the family and the seasonal employees in touch. A woman who’d picked for the family for 10 years brought her first baby to the farm last summer to meet Dan and Penny and their own children. Son Alex, a golf pro, and daughter Alina, a first-year nursing student, both join Dan’s brother, Tom, in pitching in.

“It’s a family farm—everybody has to help,” says Penny.

Photo Credit : Megan Haley

Like many farmers, she and Dan hold other jobs. Penny is an administrative assistant at Frontier Regional and Union 38 School Districts, and Dan works as district director for the USDA’s Massachusetts Farm Service Agency, which helps farmers seeking financial assistance. For 35 years, he’s gained insight into Massachusetts agriculture, which counts small new enterprises among its 7,755 farms. “It’s nice to see that younger farmer coming in,” Dan says.

With the pickers’ totes stacked in the back of his truck, Dan heads home, the wide Connecticut River sparkly through the trees. The Cape comes into view, just after a recently planted acre that’ll first be harvested this spring. Asparagus is a waiting game. Plant a field one year, pick only for a week the following year, for a bit longer the year after that, and for the season only in the third year. “But you’re not going to have true yield for five years,” says Dan, who in the meantime battles any farmer’s worries. “You start thinking, is there going to be any wind, any rain? But I just go to bed. What can you do? You just hope.”

Back in the shade of the garage, where 33,600 pounds of asparagus were trimmed and bunched last year, Dan and Penny stand in shorts and T-shirts, working away. Nearby, an iron asparagus buncher from the 1800s rests next to a pyramid of bunches similar to the one in that childhood photo of Dan.

“It’s Groundhog Day: doing the same thing day after day,” Dan says. He might sink into thoughts of the annual end-of-harvest pizza party for the crew, of the treat of bacon-wrapped asparagus, of harvesting butternut squash and sugar pumpkins to round out the year. But also of next year. Last July, Dan ordered 15,000 asparagus crowns, and this spring planted them on an acre and a half next to the garage.

That’s farming. That’s legacy. That’s the hope. That’s the life, says Dan: “I’m always thinking of next year.”

ONLINE EXTRA: If you would like to see Dan Smiarowski’s family recipe for sautéed asparagus (“preferably from D.A. Smiarowski Farms,” he jokes), go to newengland.com/asparagus.