Shore Winner | First Light

Now turning 50, the famed road race in Falmouth, Massachusetts, might just be the best in America.

With the first mile of the seven-mile Falmouth Road Race under their belt, the first group of elite male runners cruises by the iconic 19th-century Nobska Light in 2021.

Photo Credit : Ian MacLellan

Photo Credit : Ian MacLellan

There’s a scientific explanation for the feeling of euphoria that athletes call a “runner’s high”: a rush of endorphins resulting from strenuous exercise. But if a runner’s high could also be triggered by a view, it’s the one at mile 1 of the Falmouth Road Race. There, just ahead, is the landmark Nobska Light at the crest of a hill up which are coursing thousands of runners in fluorescent hues, with sailboats bobbing on Nantucket Sound beyond.

The Falmouth Road Race, which celebrates its 50th running this summer, is about more than just the scenery, however.

What started as a fund-raiser for the girls’ high school track team with fewer than 100 casual participants now attracts nearly 13,000 runners, including the best in the world, in front of raucous spectators who cheer as loudly for the stragglers as for the fleet-footed elites. It’s raised tens of millions of dollars for local charities and scholarships, helping blunt the pain of gridlock it causes for this Massachusetts town.

How this happened is a story of stubborn determination, happy accidents, and the occasional shortcut.

Running wasn’t much of a thing when the first Falmouth Road Race happened on August 15, 1973. Only 1,600 people ran the Boston Marathon that year, 12 of them women.

But that was starting to change. Tommy Leonard was tending bar at Brothers 4 in Falmouth Heights, where he worked summers, watching on TV as Frank Shorter won the Olympic marathon in 1972 in Munich, the first American to do it in 64 years; Leonard refused to pour a drink that day until Shorter had crossed the finish line.

Leonard got an audacious idea. He’d create a race in Falmouth and lure Shorter to come. He teamed up with the high school track coach and the director of the recreation center and their wives, and that August a ragtag group of mostly local runners gathered at the Captain Kidd, a restaurant and bar in Woods Hole. Their destination was the Brothers 4, about seven miles away depending on whose car was being used to measure the distance.

Two hundred people filled out the registration forms—printed on the mimeograph machine in the rec center—and paid the $2 fee. Many were friends of Leonard who worked at local bars and restaurants and played in the summer softball league, or scientists in Woods Hole. Nearly three inches of rain fell that day, and fewer than half of those who registered showed up for the start at noon on a Wednesday.

“Cats and dogs,” remembers Ron Pokraka, who ran the first and the following 45 Falmouths until his cardiologist advised him to ease up.

The winner was a vacationing college student from Michigan who had registered that morning on a whim, crossing the clothesline that served as the finish. Then the party started. Runners danced to a banjo band at Brothers 4 till 1 a.m., drinking Schlitz and eating bologna sandwiches and clam chowder—the first of many odd post-race foods that would become a tradition. In later years, spectators would watch from roofs with drinks in hand; one bar near the finish would report selling 20,000 bottles of beer on race day.

Leonard, who also worked the Eliot Lounge, the Boston bar where the world-class Greater Boston Track Club hung out, had much bigger plans, though. “He kept saying, ‘It’s going to be the greatest race in the world,’” recalls Pokraka.

Working his connections, Leonard recruited champion miler and Olympian Marty Liquori to run the next year, when the race moved to the third Sunday in August. This time, the weather was hot and humid, which has since been the case more often than not; as much as they look forward to the view of Nobska Light, runners dread the mile plus along the beach, a little later on the course, with no shade. Even champion marathoner Alberto Salazar was once felled by the heat, dumped into an ice bath, and taken to the hospital.

Liquori was beaten by an unknown Bill Rodgers (the marquee on the Brothers 4 famously welcomed “Will Rogers”), who would go on to win the next year’s Boston Marathon. And Leonard leveraged that to finally lure Frank Shorter in 1975 for a duel with Rodgers.

“Nobody knew who I was,” says Rodgers. And Shorter “was the best in the world. We got him running in this new little race because Tommy Leonard wanted him to.”

To pull this off, the race sidestepped a U.S. Olympic Committee rule that if it paid Shorter to come, he’d forfeit his amateur status. Leonard arranged for a beer company to pick up the airfare and the owner of the Captain Kidd to pay a “training stipend.”

It was all “sort of clandestine, wink-wink, behind the scenes,” Shorter says.

Shorter versus Rodgers was a huge draw. The media descended and watched Shorter pull away at the end by 15 seconds. He won the next year too, when the two returned to battle again. Not long afterward, The Complete Book of Running by Vermonter Jim Fixx spent 11 weeks atop the New York Times best-seller list, and everybody started running.

The first of a long succession of sponsors signed on: Perrier, which pitched in $5,000. Until then, Leonard had hit up local merchants for a motley assortment of prizes—handbags, a TV, a case of motor oil. Rodgers won a blender when he beat Liquori. Top runners were put up with local families, another tradition that stuck.

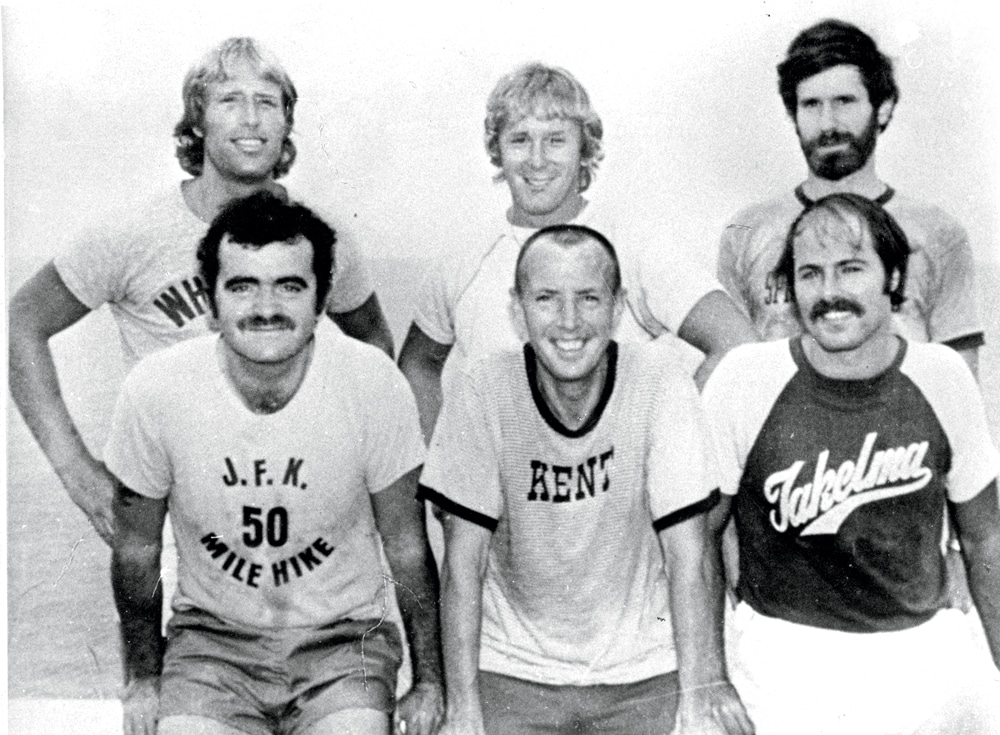

Photo Credit : Falmouth Road Race Inc.

Then, in 1980, the United States and other countries boycotted the Summer Olympics in Moscow, idling runners from around the world. Many came that year to Falmouth. New Zealander Rod Dixon won, and Norwegian Grete Waitz set a new women’s record.

It was this “confluence of happenstance” that really built the race, says Paul Clerici, who wrote its definitive history. “A true elite athlete thinks, I want to run against the best. Where are they? Falmouth.”

Soon, 5,000 runners a year were signing up. Joan Benoit Samuelson, then Joan Benoit, won the women’s division while she was still a student at Bowdoin before going on to win the first Olympic women’s marathon (and five more Falmouths). She, like Rodgers and Shorter, still comes back every year. “It’s like a family reunion,” she says.

Falmouth was named the best road race in America by Runner’s World. Sports Illustrated called it a summer essential. The prize purse grew to more than $70,000, ensuring entries from the world’s best runners; many of the Olympians who competed last year in Tokyo had run in Falmouth.

Once-a-year competitors still rub shoulders with elites in the start corral and over post-race snacks (now hot dogs and frozen yogurt bars) on the ballfield at the finish. “In no other sport can anyone of any ability just join in,” says Clerici.

Then there’s that setting. “You can take a seven-mile road race and the organizational structure and the world-class runners and drop it into Dubuque, and it could never be Falmouth,” says Bill Higgins, retired sports editor of the Cape Cod Times, who has covered most editions of the race and run several, too.

Photo Credit : Ian MacLellan

There have been some growing pains. A limit of 12,800 was eventually placed on the number of starters squeezed into tiny Woods Hole; another 6,000 applicants typically lose out in the annual lottery. Leonard died in 2019 at 85; there’s a plaque in his honor at the starting line.

But some things stay the same. Water stops are handed down in families. Bands play. An estimated 75,000 spectators line the route, many along that searing stretch of beach, in a joyful seven-mile party. Helicopters hover overhead. “It’s almost surreal,” says Karen Rinaldo, an artist who paints scenes of the race. “It is gridlock, but the town has come to accept it, and embraced it. They realize this is all part of the Falmouth experience.”

The spectators come for the elites. But they still stay for the stragglers.

“That’s what I love about Falmouth,” Shorter says. “They cheer just as hard for the last person as for the first person.”