Rite of Return | A Connecticut Migratory Bird Parade

As Connecticut’s largest shoreline park, Hammonasset Beach State Park is a place visitors naturally flock to. And what’s attractive to nearly a million sun-worshipping humans annually is just as alluring for birds, especially during peak avian travel season. “Coastal hammocks like Hammonasset are terrific stopover habitat for migrating land birds,” says Patrick Comins, executive director […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanAs Connecticut’s largest shoreline park, Hammonasset Beach State Park is a place visitors naturally flock to. And what’s attractive to nearly a million sun-worshipping humans annually is just as alluring for birds, especially during peak avian travel season.

“Coastal hammocks like Hammonasset are terrific stopover habitat for migrating land birds,” says Patrick Comins, executive director of the Connecticut Audubon Society. “It’s a big open area on a very highly developed coastline, so for any bird flying over, it stands out like a sore thumb.”

But that’s just part of the reason the nation’s third-smallest state is a major jumping-off point for birds trekking between their wintering and breeding grounds. Its 5,543 square miles encompass a rich mix of habitats, including river valleys that start leafing out sooner than inland waterways, drawing migrants with early-spring shelter and food.

Connecticut Audubon’s 21 wildlife sanctuaries reflect that variety, from the Coastal Center at Milford Point to the forests, meadows, and wetlands of the 850-acre Deer Pond Farm Sanctuary. But for eager springtime bird-watchers, it’s hard to beat the tiny Birdcraft Sanctuary in Fairfield: “It’s six acres surrounded by development, so in a sense it’s the only game in town for these migrating birds,” Comins says. “It concentrates them all into this one area, and sometimes you get amazing views of birds that you wouldn’t normally see.”

No matter where you are, you probably won’t have trouble finding these annual visitors, many of which are in their brighter breeding plumage and singing enthusiastically to mark territory and find mates. Spring migrants generally begin arriving in Connecticut in late April; their numbers peak in mid-May, when nearly 200 species are likely to be passing through the state.

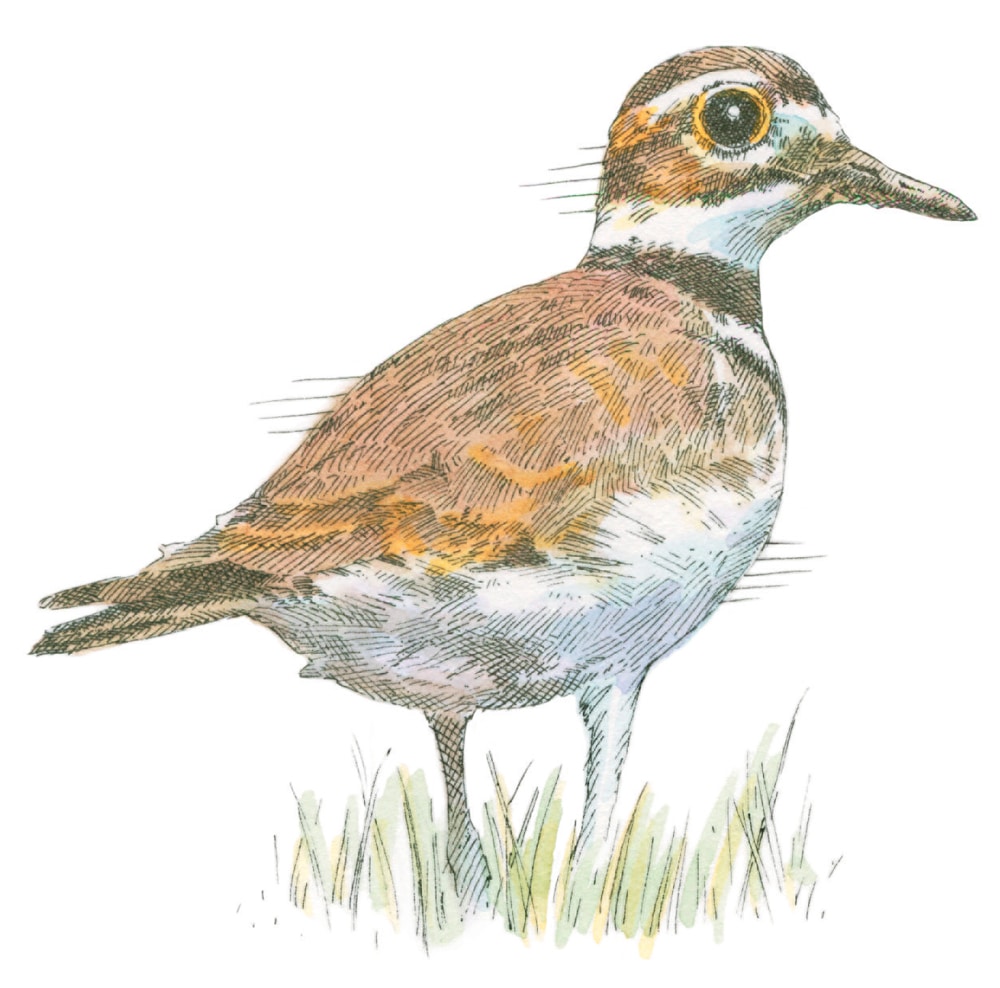

Comins’s own favorite sign of spring, though, is a bona fide early bird: a type of plover called the killdeer, after its distinctive call. “They’re one of those species that are pressing the snowmelt line and trying to get as far north as possible. You can hear them as early as March, on those first warm evenings,” he says. “It always reminds me that spring is here, when I hear the killdeer flying around at night.”

The Connecticut Audubon Society hosts its annual Migration Madness birdathon May 13-15. For details, or to learn about its many other birding programs, go to ctaudubon.org.

A sampling of spring flyers, curated with help from the pros at Connecticut Audubon:

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

Killdeer: Occasionally overwinters in southern New England but in general is considered an early harbinger of spring migration, with males closely following the melting snow line to find the best territory first.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

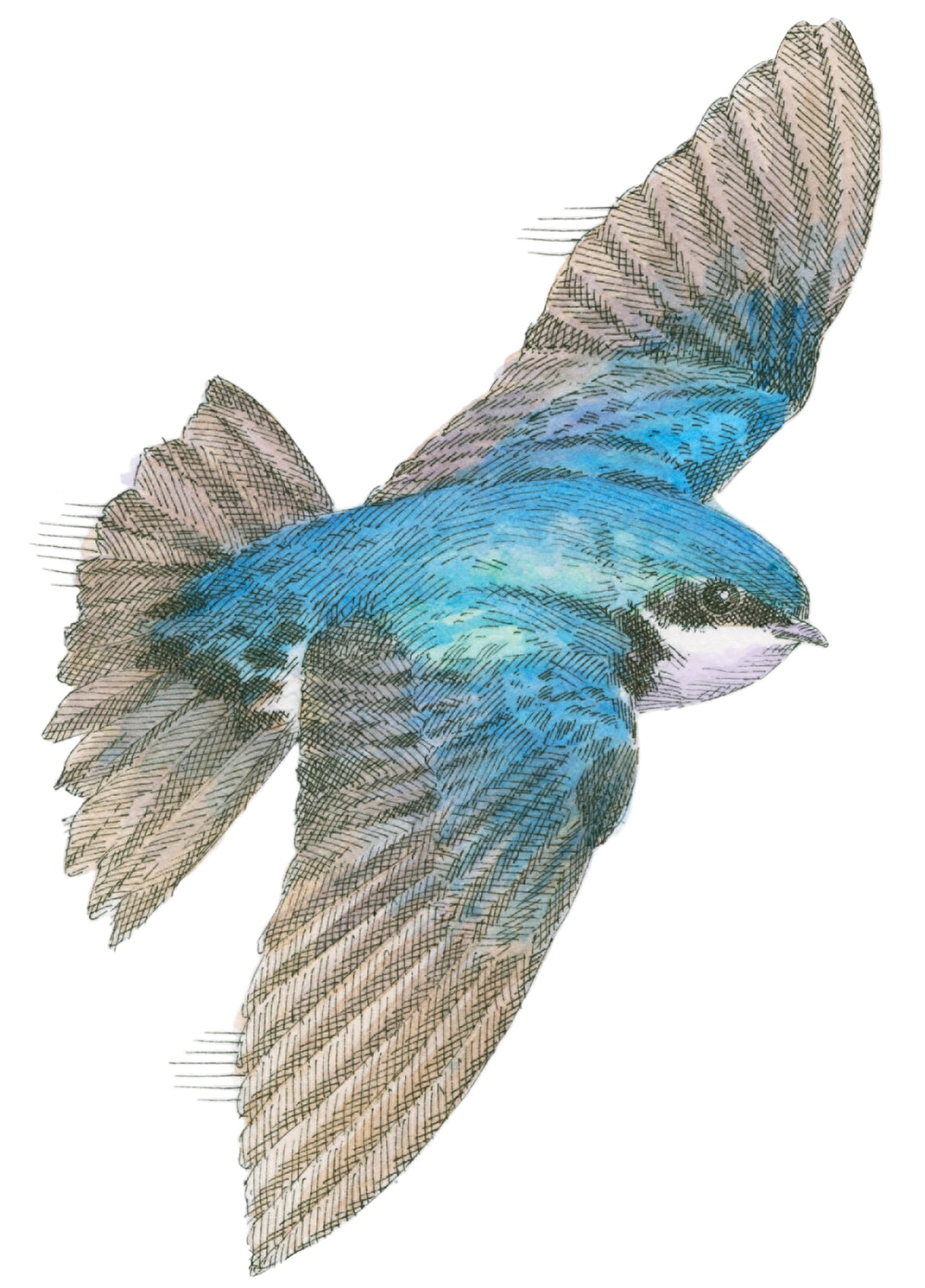

Tree Swallow: The spring return of this trim little songbird, which nests across New England, is a prelude to a bigger show later on: The autumn roosting of migrating tree swallows on the lower Connecticut River—where they gather in numbers up to half a million strong—is one of the true wonders of the bird-watching world.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

American Robin: A year-round resident in parts of New England, but largely inconspicuous in winter. Come spring, robins’ numbers swell across the region and the air once again fills with their song.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

White-Crowned Sparrow: Though sparrows aren’t often associated with spring migration, white-crowns fly though New England each year—reaching peak numbers in Connecticut, for one, around Mother’s Day—as they head for breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

Common Nighthawk: A species with one of the longest migration routes among North American birds; considered endangered in parts of New England. In mid-May, watch the skies for these migrants in late afternoon and listen for their buzzy meep calls.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

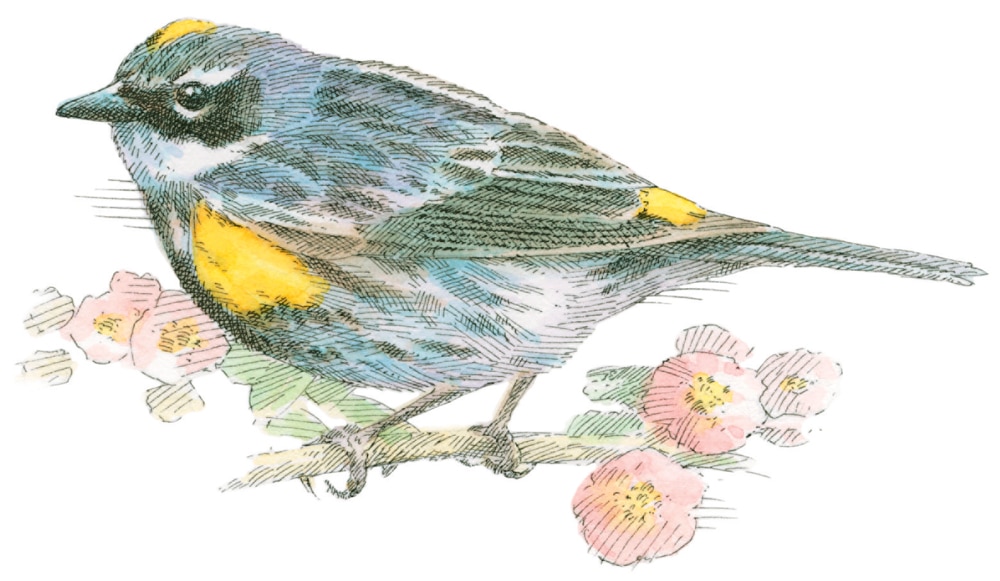

Blackburnian Warbler: Typically a May arrival, this spectacularly colored bird often perches high in the treetops; to locate, listen for the Blackburnian’s distinctive high-pitched series of tsee notes ending with a very high trill.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

Yellow-Rumped Warbler: One of the biggest joys of spring are the warblers. Yellow-rumps winter much farther north than most warblers and are among the first to show up in New England; can be super-abundant in peak migration.

Photo Credit : Illustrations by John Burgoyne

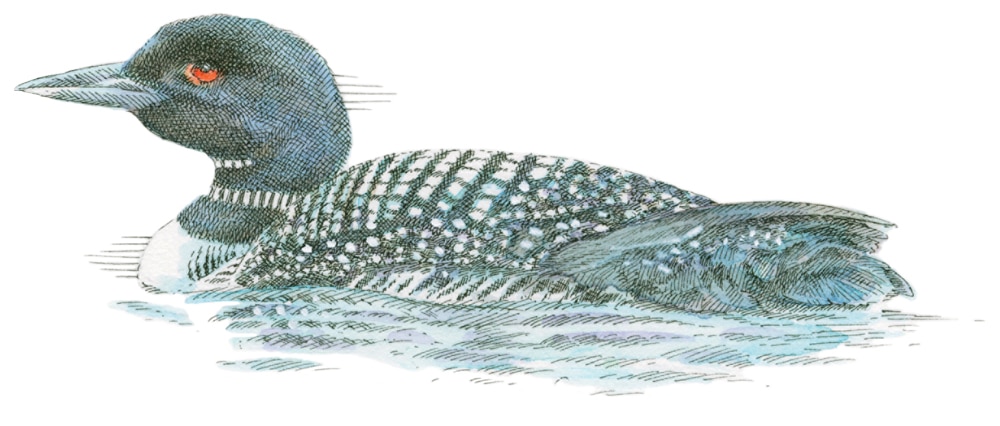

Common Loon: Though known for nesting in northern New England, loons can be seen migrating over southern areas from late March to roughly mid-May. After spring rainstorms, it’s worth checking decent-size ponds for loon sightings, along with grebes and sea ducks.