Rising Seas | New England Climate Change

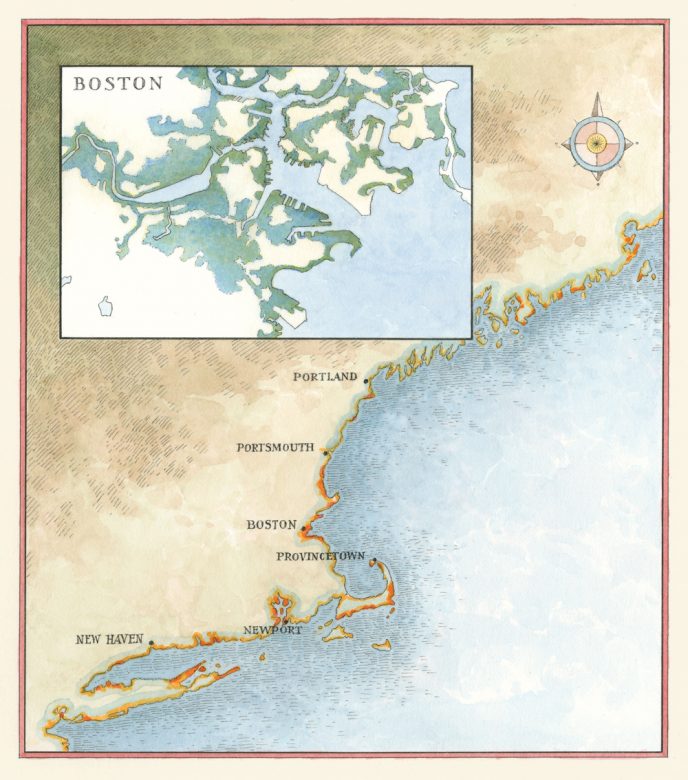

New England was built upon the coast. Its fate will depend upon how well we adapt to a future that can no longer be ignored. How rising seas are changing the New England coastline.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanOn a Sinking Island

In the morning fog the captain moors his boat, the Osprey. We can’t see Great Duck Island, which is only 250 feet away. The 46-foot boat, which belongs to College of the Atlantic, is bringing professor John Anderson and four students back to the island this morning, 16 miles from Bar Harbor, Maine, to continue their bird research.

Photo Credit : Tristan Spinski

Two students get into an orange inflatable landing boat that’s tied to the Osprey’s stern. It’s packed with gear—watertight boxes and plastic jugs and backpacks and two long oars in case the outboard motor quits. Everything has to come to the island on this rubber craft: peanut butter, potable water, gasoline, lumber (three planks on this trip), and propane tanks.

The boat’s silhouette disappears in the fog, and moments later the fog thins so that the day is both occluded and bright at the same time. I can see the island’s little white boathouse, the only building on this shore, and the long ramp down to the water.

I board for the next landing. Arriving at the island, the orange craft runs right up the slippery ramp, which looks like a wet roller coaster track, and Anderson immediately walks me out about a quarter of a mile, no more, from the boathouse. Great Duck is a mile and a half long and all of 220 acres. At a time when gulls were hunted to near extinction, Great Duck was home to the last big gull colony on the East Coast. The Nature Conservancy acquired the island in 1998, and today shares it with the college, the state of Maine, and a private summer resident. The college owns about 12 acres, which includes the lighthouse, the head keeper’s house, and two boathouses.

We walk on an old track through a wind-thrown spruce forest until we come to a low meadow sitting before the next rise. Like a good teacher, Anderson lets me look things over, saying nothing, until I ask him for an explanation.

“You’re basically at sea level, where you’re standing right now,” he says. “This is very typical of a lot of the islands up and down the coast.” We are standing in a “surge channel” between two small granite domes. A natural seawall of cobbles keeps the sea out—for now. The sea has rushed in twice in the recent past, during a hurricane in the 1930s and when a big winter storm in the 1960s filled the channel for weeks.

Photo Credit : Tristan Spinski

“With a six-foot sea-level rise”—one current forecast for the end of the century—“we’re not going to have Great Duck anymore. We’re going to have Little Dinky Duck and Medium-Sized Duck,” he says. “And this is going to be a sea channel.”

Anderson reviews some of the islands he has studied for Acadia National Park. Shabby Island is a marsh surrounded by a rocky berm—“end of island,” he says. Great Spoon Island has some higher places for the gulls to nest, but all the prime eider duck habitat will flood out. Schoodic Island, Acadia’s main seabird island, “will be reduced to three chunks of rock. No eiders, no guillemots. Little bit left for cormorants and gulls, but all pressed together in a very small space. I don’t think they’ll stay. The low islands are in trouble.”

Walk a few hundred yards on this one small island, and you can see that the rising sea is about more than seawater and shorelines.

—

For months I’ve been turning up along the coast and saying: Show me what we’re going to lose, show me what will be underwater, show me the shape of things to come. In each place I am standing at the corner of Loss and Change. And in each place I have the same conversation: This is changing—fast. This conversation is going on all along the East Coast and, in fact, the world over.

I’ve been rowing against my own belief in rock-steady traditions, in wanting to believe that the iconic landscape that we all love—the islands of Maine, the famous coastal towns, you name it—will abide. That it will all be the same as it ever was, the same when the next generations discover this place. But that is no longer our future.

Think of the coast as a long necklace of beloved places, coves and marshes, peninsulas, docks and bays, clam shacks and lobster pounds and ice cream stands. Summer lives here. Summer stories are about the joy of returning to the same treasured haunts every year. Everyone gets older, children leave home, careers flourish or stall, but come summer, people can head to their favorite beach, or B&B, or family retreat. They can exhale. They can do as they have done since they can remember.

When just one of those places closes, it’s like a thread snaps. It’s like a rude shove in the back, a push to keep on moving along your life’s short timeline. The yearly pilgrimage, the eternal return, is cut off, and people miss it deeply. Now magnify that by a thousandfold up and down the coast, from Maine to Connecticut. Good-bye to beaches, marinas, beach houses, marshes, lighthouses…. Who can face that? I know I can’t.

—

In the history of life on Earth there have been five mass extinctions, periods in which thousands of species died off. We’re living in the midst of the sixth mass extinction, say scientists, the greatest since the dinosaurs vanished, and we’re causing it. “No other creature has ever managed this, and it will, unfortunately, be our most enduring legacy,” writes Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and author Elizabeth Kolbert.

What’s happening in the Gulf of Maine is a part of this great dying-off. Maine’s islands are home to about 50 percent of all nesting seabirds in the eastern United States—and that population is in turmoil.

Seabirds are “declining very, very rapidly,” says Anderson. “Depending on who’s doing the numbers, we’ve had between a 40 and 70 percent decline in gulls here in the Northeast in the last decade. If this were any other group of birds, we’d have headlines and national boards of inquiry, but because it’s just gulls, nobody cares. But we care—and part of what makes us very nervous is that everybody is seeing a big decline in gulls all around the northern North Atlantic.” Bird by bird, we are losing the world.

Anderson, 60, is an impressive teacher. Born in New Zealand and raised in Britain, he has taught ecology and natural history at College of the Atlantic for 30 years. In our short walk he has set the Gulf of Maine spinning. It’s a bit much to take in. This is only a glancing tour of the natural and unnatural history of the islands, but the story is all about change. The natural changes and the ones we’ve caused are as knotted up as the storm-wracked fishing lines that wash up onshore. The Maine coast that we see today, the stunning place of deep pine green rimmed with granite, is only 5,000 years old. When you begin to realize that 5,000 years in the earth’s time is but a weekend getaway, you feel the planet spinning, you feel everything moving—including yourself—which is closer to the true condition.

Forget for a moment the distant forecasts, and all the arguments about climate change. We first have to accept that the earth is changing and always has. Now, it is changing very fast due to our carbon-producing ways. If we can learn to see that marshes move, that barrier beaches belong more to the sea than to the land, then we can begin to listen to what the scientists have been trying to tell us.

—

We walk to the old head keeper’s house, the college’s headquarters for its island research. The students are getting ready to go to the lighthouse, where they’ll observe the herring gull colony. Later they’ll suit up in black trash bags (for obvious reasons) and walk among the gulls to do a “chick check,” weighing the young in the nests. One student is reviewing the images from cameras she has set out to watch the burrows of Leach’s storm petrels. They are the most numerous birds on the island—about 5,000—making this the largest studied petrel colony in the eastern United States, a point of pride for Anderson and his students.

When Anderson did his three-year study for Acadia National Park on the future of the major seabird islands, he had to keep revising his forecast. The climate scientists kept increasing their estimate of how much the sea will rise—it’s the fastest rise on record for the past 28 centuries. Scientists are shocked at how fast the earth is warming, with each year’s temperatures topping the previous years’. The ocean science is complicated. The ice melts, the sea rises; the sea warms, water expands, the sea rises more; the water becomes 30 percent more acidic; the Gulf Stream may slow, with dire consequences. We’re conducting an irreversible, Earth-sized experiment.

“The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than any other body of its size in the world. When you have that sort of shift in temperature, all kinds of other things happen,” says Anderson. The temperature had been rising by 1 degree Celsius every 40 years; it’s now warming up 1 degree every four years. In water just a couple of degrees warmer, the oxygen content is reduced, and some fish, such as tuna, can’t survive. Algae blooms and pathogens increase.

Photo Credit : courtesy of College of the Atlantic

Photo Credit : courtesy of College of the Atlantic

“One of the immediate problems is softshell, which is a fungal infection that basically makes lobsters look like Frankenstein’s monster,” Anderson says. One-third of lobsters in southern New England have the disease, and it’s creeping north. Lobsters make up three-quarters of the value of Maine’s fishery, and while there have been record catches recently, there are signs of trouble, too, such as a decline in the number of the youngest lobsters. Scientists know it’s difficult to predict the lobster population. And it’s getting more difficult as climate change is creating what they are calling a “brave new ocean,” an ocean they don’t understand.

The Gulf of Maine, on the eve of great changes, is already stressed. The planet is on course to exceed the limit set in the international climate agreements: holding warming to a 2 degree Celsius (3.6 degree F) increase. An Earth hotter than that could bring down civilization, say the climate scientists. Though it’s widely accepted that there’s going to be a significant loss of ice at the poles, “that’s not actually the worst-case situation,” Anderson says. “Worst-case situation is the Antarctic ice shelf goes. If the Antarctic ice shelf goes, Bar Harbor goes with it. It’s not just going to be seabirds. It’s going to be New York.”

Anderson is sitting on an old couch under some maps of the island. And while his British accent never loses its crispness, he is weighed down by what he’s saying. He slumps deeper into the couch. It’s one of those moments when people speak directly and say, Here, this is the burden I carry.

“And honestly,” Anderson continues, “I don’t worry about wildlife and global warming. All of the species you’re looking at have survived massive periods of global warming, global cooling. The thing that I’m really terrified of is how these guys are going to deal with global warming and seven and a half billion humans not dealing with it very well.” His frankness is jarring.

Superstorm Sandy, which caused $65 billion in damage in 2012, making it second only to Hurricane Katrina, was just a modest storm. Sandy, many say, was a preview. “Imagine when we get a real superstorm, when we’ve had six feet of sea-level rise,” Anderson says. “The whole of Lower Manhattan is going to go under. What are we going to do with six million New Yorkers? That’s the question. We’re also going to lose New Orleans. And we’ve got two choices at this point: We can evacuate New Orleans carefully and slowly and deliberately, finding new places for people to live, finding new jobs for them, settling them in better places. Or we can evacuate them in the rain on buses with what they can carry. The one thing we don’t get is, we don’t get New Orleans. My students are going to live to see this.”

And yet here we are. It’s a glorious day. The fog gathers, thins, and gathers. The students are busy counting chicks, studying the gulls. “Think of how lucky we are,” says Anderson. “We’re getting paid to drive around the coast and look at beautiful birds and beautiful islands. Isn’t this a wonderful place?”

Doggerland

In the 19th century, fishermen in the North Sea off England would sometimes pull up odd things in their nets. Clumps of peat. Deer, bison, bear, and horse bones. How strange, they thought. How did these animals get 60 miles from shore? As trawling increased in the 20th century, they found more things. In 1931 a trawler brought up a harpoon carved from an antler. A beautiful object, like something the Inuit would make.

With the boom in North Sea oil, the sea floor was extensively mapped, revealing the valleys, rivers, lakes, and hills of a lost land. The archaeologist Bryony Coles named this place “Doggerland” in a 1998 paper. Part of it was located on what today is Dogger Bank. Doggerland connected England to Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, and northern Germany. There was no North Sea. The English Channel was a tidal estuary, a river snaking through a marsh to meet the sea. Then, as the great ice sheets up north began to melt, the sea rose, the English Channel formed, and Doggerland became, after many years, an island. Small bands of hunter-gathers lived off the salmon run for months. As the sea rose, the marshes flooded, the land flooded, and at last on a day lost in prehistory, about 7,600 years ago, Doggerland’s people left for England. Today there are people in Britain and Australia who can trace their lineage to Doggerland. DNA tests link them all the way back to that North Sea Atlantis.

For an up-close look at the impact on your town, go to coast.noaa.gov and search for “Sea Level Rise Viewer.”

Photo Credit : John Burgoyne

Doggerland is not something most people know about, but it is now squarely in our future.

Doggerland is our story. Under the current forecast from the scientific research organization Climate Central, about 760 million people—more than 10 percent of the world’s population—will be left homeless in the next century by the rising sea. Each bit of warming today locks in the changes for centuries to come.

—

An American Doggerland is already happening. Half our population and a legion of museums and historic sites are on the coast. “Many of the United States’ iconic landmarks and heritage sites are at risk as never before,” says the Union of Concerned Scientists. The Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and Faneuil Hall lead a list that includes the Kennedy Space Center, Hawaiian sacred sites, and enough historic cities and museums to fill the itineraries of untold vacations. Liberty Island flooded during Sandy, forcing the Statue of Liberty to close for more than eight months. In Boston, if Sandy had hit just six hours later, at high tide, more than 6 percent of the city would have flooded. Boston has weathered extreme high tides (three and a half feet above average) 21 times since official records began in 1921—half have occurred since 1994. By midcentury, Boston could see a “100-year flood” every two to four years, and every year by the century’s end.

Photo Credit : Mike Chase/housely.com

The changes are coming fast. Archeologists are adopting triage, the practice of battlefield medicine that sorts among the wounded, as they rush to work on coastal sites that are being wiped away by storms. About 95 percent of the National Park Service’s archeological sites on the historic Virginia island of Jamestown will likely be lost in 50 years, and by the end of the century this “birthplace of America” will be underwater.

Museum curators and preservation experts are among the first to realize the new realities of an American Doggerland. In March 2016, 350 professionals met in Newport, Rhode Island, for the first-ever “Keeping History Above Water” national conference. Sarah Sutton, a museum consultant, summarized the situation: “If you’re within two to seven feet of sea level today, then saltwater is in your future this century. If, like many early cultural sites, yours was built on land that was once wetland, then saltwater is already in your basement. What to do: document, protect, salvage, move, or abandon?”

Think of our museums and historic and archeological sites like that treasure of antiquity, the lost Library of Alexandria, says anthropologist George Hambrecht. “It is incredibly valuable, and it’s on fire now.”

Puddle Dock: The Sea Returns

In the basement of the Shapley-Drisco House, the sea is rising. High tide covers the bottom steps of the basement stairs; the ocean is just a couple of feet below the first floor. Upstairs, some floorboards have popped free and the brick in the fireplaces is crumbling.

The Shapley-Drisco House belongs to the Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The two-family house has been restored to reflect two different times, 1795 to the right, as you enter, and the 1950s to the left. To that, add the 21st century asserting itself in the basement. This house lives in three centuries, one of which, unseen by museum visitors, threatens the other two.

The Shapley-Drisco House faces what was once Puddle Dock, where the tides rose and fell eight feet. Before Portsmouth was settled, Puddle Dock was a tidal estuary. Between 1905 and 1908, it was filled in. Now the sea is returning. At high tide, saltwater is only two feet below the broad central lawn that replaced the old waterway. The basements of the four houses facing Puddle Dock are “right on grade with saltwater infiltration,” says Rodney Rowland, the museum’s director of facilities and special projects. Beyond Puddle Dock, a small rise puts much of Strawbery Banke about 10 feet higher, but not out of danger.

Photo Credit : Tristan Spinski

On a crisp, postcard-perfect day, the small museum village is as trim and tidy as a scale model. The houses, uncrowded by cars and utility wires, seem like ideal images of themselves. Standing on Puddle Lane as Rowland points out the other houses, I realize we are at the bottom of a bowl. In a storm, all the water “comes right here, because we’re the low point,” he says. “I’ve seen storms where some of our historic boats are floating along Puddle Dock. You would have thought we’d been in some time warp. We’ve got these Strawbery Banke dories floating across Puddle Dock. That water has nowhere to go. The ground is saturated. The storm drains are saturated. It just sits. That’s the big problem. We’re at ground zero.”

After examining the Shapley-Drisco House’s basement, we walk down the lane to the Lowd House, where the basement has been repaired and defended against the sea. “The damage to the original chimney base, built in 1810, was so extensive from saltwater infiltration that you could crumble it with your hands. There was no saving it,” Rowland says. No historic museum wants to lose the original object, but they had no choice, and replaced it with granite. They also lost the 1810 summer kitchen that was in the basement—that part of the house’s story is gone. They built a perimeter drain in the basement and added soil, rock, a moisture membrane, a concrete cap, and a basin with a sump pump. I can imagine the museum labeling this as an exhibit one day: “Climate Change: Early 21st-Century Response.”

The Puddle Dock houses are an indicator of what’s to come. What will happen to the rest of the museum depends on the forecasts, and whether we find a way to stop dumping carbon into the atmosphere. If there’s a two-foot rise in the mean sea level, Strawbery Banke may survive, but it could face damaging storm surges, which push more water toward Puddle Dock. If, as other forecasts predict, there’s a three-to-six-foot rise by century’s end, Strawbery Banke could become a wooden Venice. Beyond 2100, the sea will probably rise even faster.

“We’re never going to be able to combat the sea rising and the river infiltrating this neighborhood,” says Rowland. “My opinion? We’re not going to move, but we are going to lose historic resources.”

Strawbery Banke’s founding, though, may hold a clue to its future. In 1958 local citizens saved the buildings from being flattened by urban renewal. It was a bold idea, one without a road map, and it has taken years for the museum to evolve. They are just now restoring their last three buildings. Strawbery Banke will have to be rescued again, but no one knows how yet.

Change has always been a part of the story the museum tells. It was never meant to be a time capsule. “It’s one of the reasons Strawbery Banke is unique,” says Rowland. “Most museums pick a fixed period or a decade; we do 300 years because we want to show people how this neighborhood evolved over time. There’s no question in my mind that our response to sea-level rise will be part of that story.”

Sandy: The Once and Future Storm

When Evan Griswold was 7 years old, in 1954, his mother led him out into the eye of Hurricane Carol. The sky was bright blue; the surf raged. They ran all the way down to the beach. He saw the front of a house vanish into the waves. He’s never forgotten it, a lesson that’s still with him more than 60 years later.

On a sunny day I walk out to Griswold Point with Griswold and Adam Whelchel, director of science for the Nature Conservancy in Connecticut. Griswold Point, at the mouth of the Connecticut River, is one of those places where you feel yourself pinned to a map, where you can imagine yourself as seen from above. We look south to a marsh, a barrier beach, and the Long Island Sound, and west across the Black Hall River to more marsh and the white stone lighthouse commissioned by George Washington that marks the entrance of the broad Connecticut River. Piping plovers nest on the barrier beach. The yip yip yip of ospreys fills the air; a light breeze keeps the mosquitoes moving. Griswold’s old Lab, Maya, follows us, looking like a small black bear in the tall grass, until she’s distracted by the lone elm in the hayfield. Ospreys land there and drop bits of fish, an irresistible treat for her.

Photo Credit : Tristan Spinski

Evan Griswold’s family has lived here since 1645, back to the day Matthew Griswold was granted 10,000 acres, land that stretched from Old Lyme to New London. Growing up, Evan Griswold spent his summers here, and in 1983 he and his wife, Emily, had a post-and-beam house built under the trees. He sited it back from the marsh—quite far back, he thought. When Superstorm Sandy hit, the tide kept coming in for three days. The Long Island Sound rose until it was about 50 feet from his house, just down a small slope. Griswold is a proper host as he shows us around, but also a bit of the real estate agent that he is, efficiently walking a prospective buyer through a house.

The changes that he’s seen in the marsh during his twice-daily walks over the past three decades are quietly persistent. He shows us where the stone wall his ancestors built falls right into the low-tide mud flats of the cove. This was once pasture. He shows us where the bright green of salt meadow hay (Spartina patens) has retreated and almost disappeared as the rougher, duskier salt marsh cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) advances. The salt marsh cordgrass marks the advance of the tides. It can live where it is submerged daily.

And the changes are also large. We tour a neighborhood that flooded in Sandy and was without municipal water for six months. A rebuilt house stands awkwardly on stilts 13 feet high. There are signs up around Old Lyme announcing meetings to talk about “resiliency,” about preparing for a new, post-Sandy world. The three lectures were poorly attended, lost in the festivity of early summer—tennis, tag sales, and all the rest—but the future is hurrying in anyway. Main Street is a mere 20 feet above sea level. Most of the town’s residents depend on wells and septic systems. The rising sea is starting to salt the wells and carry nitrogen from the septic systems into the sound. This will be very expensive to fix.

The post-Sandy reality was vividly presented to Old Lyme in the new flood maps drawn by FEMA. People are angry at FEMA: “I’m in a flood zone? Do you know what this will do to my property value?” But Griswold is uniquely positioned to see both sides. Before he began selling real estate, he trained as a forester, and he has served as the executive director of the Nature Conservancy’s Connecticut chapter.

“It’s a creeping crisis,” he says. But it’s as if climate change is happening in an invisible spectrum, a bandwidth of light that we won’t see until it’s too late. The world changes inch by inch, and when a big storm blows the sea inland we are finally forced to see that we are living in a new world.

It’s hard to imagine, says Whelchel. Climate change can seem to be a gentle thing on such a fine day. The ospreys are thriving, the Long Island Sound sparkles, the long tenure of the Griswold family here suggests a comforting continuity. “So how do you convince people on a beautiful day like today that there was ever anything like a nor’easter or hurricane?” he asks. As for sea-level rise—“What’s that?” And while the flooding from a hurricane is temporary, “sea-level rise is permanent. It’s permanent inundation. There is no going back from a sea-level-rise increase.”

Whelchel is cofounder of a pioneering program to get people to see the coming changes. He works with all 24 of Connecticut’s coastal communities, home to about a third of the state’s population, running workshops to help towns plan for the rising sea. Since starting the Coastal Resilience Program in 2007—reportedly the first of its kind in the nation—he has brought it to 14 states and eight countries.

One of his tools is a bit of shock therapy: aerial photo maps showing in red the houses, schools, and roads that will be in daily conflict with the tides. “Where’s the road going to be? Where’s the neighborhood going to be? Where’s the boat dock going to be? Where’s the beach going to be?” Whelchel makes it local, even personal. That’s your living room going out to sea.

The photos are marked to show where the marshes are going to move. Saving marshes is essential to protecting the coast. Healthy marshes absorb storm surges, purify the water, and serve as a nursery for the fish we eat. Marshes naturally respond to the changes in the ocean. As it gets too salty, they move back. Essentially, over time, they walk away.

Photo Credit : Tristan Spinski

“Marsh advancement” (the marsh walking) is the central metaphor we lack: We have to move. The sea is going to move; animals and plants are going to move. We have to move our thinking and our planning and our politics. The usual story is about anguished efforts to hold the sea back from shoreline cottages with seawalls, sandbags, dune restoration, and millions of dollars of sand. But we need a new approach: We have to flex, to bend. To call it “retreat” disguises the new thinking required. We have to imagine a changing world. We have to admit that every action we take has consequences, even if it cannot be neatly tallied. We have to live with uncertainty.

We need to be “prudent,” advises Whelchel. “That is such a hallmark of being a Yankee, right? Thinking forward and being prudent. That’s what it’s all about. And by not considering sea-level rise, it’s just not prudent. Why wouldn’t you, if it’s going to affect you? Why wouldn’t you turn that to your advantage somehow?”

He’s guardedly optimistic. Before Sandy hit, attendance at his workshops was sparse and usually included a few climate-change deniers looking for an argument. These days, he says, “people are asking the right questions, and maybe even making some smarter decisions because of that. But the transformation to a sea-level-rise-ready community, or a resilient community, whatever you want to call it, is a little beyond us at this point.” He goes on to note that Old Lyme was one of the first places to be settled in New England. The land is marked by nearly 400 years of decisions “about what goes where and why. People are not going to change immediately.”

We haven’t really begun to reckon with this, Whelchel says. “We spent close to $14 billion post-Katrina on New Orleans. A key question for me would be: Can we sustain that level of investment when we add on a Houston, a Miami, a Los Angeles, a San Francisco, a Boston, a New York, a Seattle? And that’s not even the Mississippi River communities. How are we going to choose which cities and towns to protect? What would it cost to secure Boston, Portsmouth, Hull, Chatham, Falmouth, Providence, Gloucester, Portland?” It’s a prescient roll call: Since we spoke, hurricanes have flooded Houston and paralyzed Puerto Rico.

Whelchel continues the story beyond the next decades. “At some point in the future we’re going to stop thinking about Connecticut’s coast,” he says, “and we’ll start thinking about the Archipelago of Connecticut,” a chain of islands where today there are roads and towns. Call them after the places we know: Fairfield Island, Westport Island, Branford Island. And somewhere under there will be Griswold Point, a New England Doggerland.

I think about that day 7,600 years ago when the inhabitants of the sinking Doggerland Island finally left. Were there those who refused to go, who tried to turn back the rising waters with their disbelief? Did they stay behind, blinded by their own denial? If so, then the Doggerlanders were a lot like us.

I finished reading this with tears in my eyes. I live in Kansas now but grew up in Newport, RI. I have beautiful memories of New England. It makes me heartsick to think that Newport and my lovely childhood house just up from Second Beach in Middletown could some day be under water. I have come “home” many times to visit over the years and jokingly said that Aquidneck Island would surely start sinking from the weight of all the condos being built and “off-Islanders” moving in. 😉 Please send this article to the senators and congress people. I don’t know what can be done, but maybe this can open some eyes and make them think about our children’s future . . .

the world always turned a blind eye to nature, remember our factories pose on dumping waste into our rivers. when will we learn?

Hurricanes are not caused by climate change. Climate change is a natural phenomenon. It is not caused by CO2. I consider this article to be something of a propaganda article.

MaryLS- Even if you think that climate change is a natural phenomenon, the point of the article is valid. People are going to have to move back from the rising sea; just as the people of Doggerland did 7,600 years ago.

Iceland was once covered with forest; and Greenland had farms and other signs of year-round habitation.

Mary and Frank–your assertions will not make a hill-o-beans difference in affecting reality, my friends. And I suspect you’ll be dead and gone 15 or 20 years from now, when the rest of us will have to deal with human-caused global climate change (yes, driven by CO2 emissions) and its impacts on our coasts and so much more. For the rest of people who wander into this comment section, it’s well known and accepted by the vast majority of climate scientists that human-drive climate change is underway and will have devastating consequences in the form of sea level rise and negative impacts on economies and health. We are already feeling these impacts–but folks like Mary and Frank, will continue to show up on sites like this and assert–with zero evidence–arguments to the contrary. Read some actual science instead of commenting nonsense.

The fundamental flaws in the arguments of the ‘warming’ advocates are both scientific and contrary to human evolutions.

There is compelling scientific evidence that the ocean off the coast of Maine is only going to rise about 1.88 mm a year, or about 7.99″ (0.66 ft.) per century. To be sure, record high tides and coastal storms will exacerbate this, but remember has been recorded since the 1600’s in Halifax and this data set since 1912.

While many variables go into rising sea levels, they have for a long time bringing up the second point which is coastal dwellers including shore bird will move to safer ground. Forecasts leave out the fact that as habitat changes, new habitat emerges and living things move with it. We adapt, and don’t sit in beach chairs waiting to drown.

“Prudent” may work for some, unfortunately few have the gift as it were to assess a situation and implement a practical course of action, or for that matter assess the situation as it lays right in front of you. Another compounding factor is to many folks ‘choose’ to ignore or just get in line behind another ignorant ‘leader’. I grew up as an islander, the sea and all that comes with it is nature at its most majestic and powerful. Do not underestimate the force of Nature. Until folks are ‘forced’ to remove the ‘blinders’ of delusion very little will be accomplished. It is not pragmatic or realistic to continually waste money and efforts into ‘trying’ to rebuild or hold back nature. It is seriously flawed to consider the pre-industrial world norms to predict or prognosticate climatic cycles in a post-industrial world. Cause and effect is not always clear-cut and evident to the blindly-biased, filling sandbags won’t hold back a flooding sea, and neither will levies or seawalls. Wildlife adapts to natures incursions, simply resettle in a safer place. Until of course mankind decides they want that piece of land too. Everyone has a choice – be part of the solution, or stay out of the way of those willing to do the work.

Google Sea Level NOAA Battery for a chart of sea level measurements representative of world wide conditions and the oldest for the USA, back to c1850. The trend is rising very very slowly but there is no inflection point showing any influence of warming. None. How anyone that calls themself a scientist can overlook this is the principle mystery of 21st century science.

Thank you for this article and the other articles on climate change and its affects in the March/April issue. I live in Colorado but grew up in New England and return at least once a year to New hampshire and Maine to enjoy the joys of nature in the mountains and along the seacoast. I have always been an environmentalist (although not a strict preservationist) and I am becoming increasingly alarmed at the affects of global warming on our environment. Particularly concerning is the attitude of many of our leaders who deny that climate change even exists! We can only ignore this issue at our peril. Thanks again for highlighting these concerns.

Bob C.