Shark Teeth, Pearly White | Yankee Classic

Yankee Classic: June 2000 Captain Charlie Donilon is a whorl of energy in a straw hat as he demonstrates the rules of the game inside his aluminum shark cage. Glistening with sunblock and grinning with mischief, he snaps his arms forward as if warding off an imaginary tackler. “Keep your camera between you and the […]

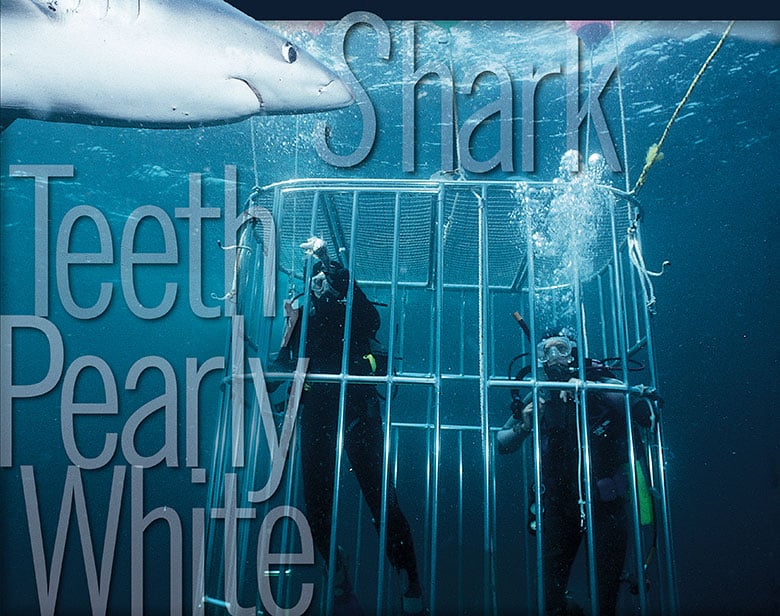

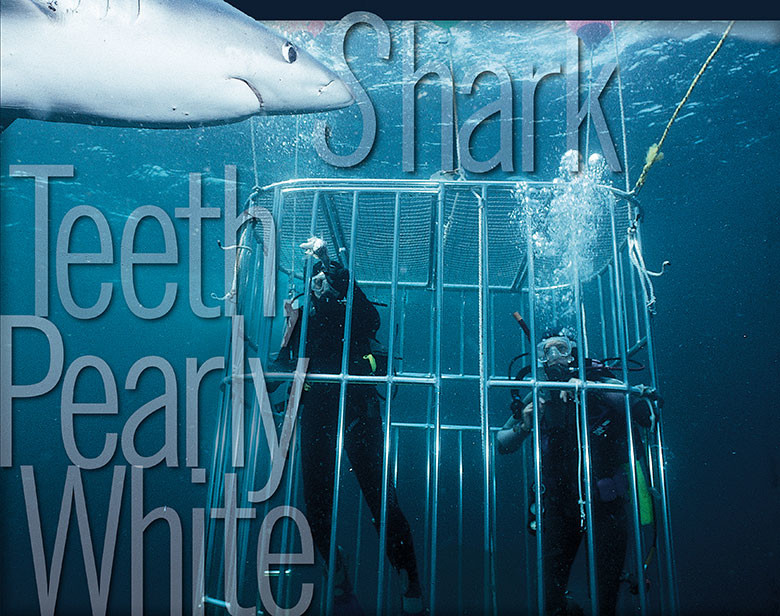

A blue shark swims past a new breed: ecotourists inside a viewing cage.

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Photo Credit : Brian Skerry

Yankee Classic: June 2000

Captain Charlie Donilon is a whorl of energy in a straw hat as he demonstrates the rules of the game inside his aluminum shark cage. Glistening with sunblock and grinning with mischief, he snaps his arms forward as if warding off an imaginary tackler. “Keep your camera between you and the sharks,” he tells the four scuba divers who stand on the deck outside the cage watching his every move, “in case you have to give a nosy one a poke.” Once Donilon’s cage is lowered over the side, the divers will be inside and the sharks outside, swimming free.

This bit of advice is what passes for a heads-up on Donilon’s playground, somewhere beyond sight of land about 30 miles south of Narragansett Bay. The four divers are aboard his 35-foot sportfishing boat, the Snappa, to swim in his custom-designed shark cage. At heart a shark hunter, Donilon scaled back his old catch-and-release sportfishing business six years ago to pursue a peculiar new kind of ecotourism. He gives divers the chance to see New England’s most ancient and mesmerizing predators in their own element. On this voyage, no sharks will die. Donilon has to make sure no divers do either.

Stepping from the cage, he tells today’s customers what to expect. They have driven in from Massachusetts, and only one has dived among sharks before. “Toward the end of the afternoon, the sharks will have been in the chum for a long time, and they’ll be more aggressive,” Donilon says. “That’s when people get bit.”

One of the divers, Maureen Kirkpatrick, a civil engineer from Walpole, winces. Shortly after sunrise, when the Snappa eased out of the protected Harbor of Refuge near Point Judith, Rhode Island, Kirkpatrick thought the cage looked safe. But now a hole in the script has become apparent. Once the cage is in the drink, the divers have to swim across 25 feet of open ocean to get to it. That 25 feet suddenly seems like a long way to go, especially when burdened by tanks and weight belts, with sharks patrolling nearby.

“Did you have to say bite?” she asks.

“It happens,” Donilon says. “They bite you. And then they let you go.”

Minutes later, the divers follow Charlie’s cue and shove the cage overboard. It sinks slowly into the rich blue swell and comes to rest at the end of its ropes, suspended two feet beneath the surface. The open water between the boat and the safety of the cage yawns before them.

While his customers contemplate the gap, Donilon sets to work attracting sharks. With a wickedly thin fillet knife, Donilon dices butterfish into pieces the size of quarters, which he flicks into the sea. The silvery chunks tumble into the depths, a twinkling constellation of shark-attracting chow. Then he ties the remains of a striped bass to a heavy rope and lobs it over the side. Before stopping, Donilon had poured a bucket of wormy-looking stew into a baitwell that circulates with the sea, so his boat exuded a plume of fish guts and blood astern. His goal is to create a shark highway with his divers at the end. Now, with the Snappa’s diesel quiet, the boat bobs on a gentle swell. The wait for sharks begins.

* * *

The waiting, as it happens, might take a while. Throughout New England’s offshore waters, shark numbers have dropped to historic lows, one part of a pattern now documented throughout the Atlantic. The collapse followed a shift in commercial fishing effort late in the 1970s, when vessels began targeting sharks to meet international demand for fins, the prime ingredient in an expensive Asian soup. The fin market encouraged a practice that attracted conservationists’ anger: Crews winched aboard sharks, hacked off their fins, and pushed the writhing, mutilated fish back into the sea, where they spiraled for the bottom and a slow death. These days, the United States has banned finning within 200 miles of its Atlantic coast. But other markets keep the shark trade robust.

Shark teeth and jaws sell as curios; spines are ground into a white facial powder; the livers yield oil; the cartilage has been used in cancer research, and the steaks of some species serve as an alternative to swordfish, itself in decline. Not all sharks are sold, however. Millions are killed by vessels harvesting other fish, a side effect known as “by-catch.” Others are dispatched by sportfishermen who reel in sharks for kicks and as tournament prizes. Many of these sharks end up in landfills or are dumped offshore.

All of this fishing pressure has had a predictable effect. According to 1995 data from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the abundance of valuable shark species along the East Coast fell by 50 to 75 percent during the 1970s and 1980s. More recent data indicate some species have fallen by 85 percent. Among the imperiled sharks are some of the most impressive, including the shortfin mako, the great white, the porbeagle, the sandbar, the scalloped hammerhead, and the basking shark, a harmless krill-eating behemoth that can exceed 30 feet in length.

The prospects for depleted shark species are not good. Unlike most fish, which engage in spawning orgies that can yield enormous hatches, sharks grow slowly, mature late in life, and bear very few young. “Sharks reproduce more like cows and polar bears and people than they do like other fish,” says Wes Pratt, an NMFS biologist and shark specialist who lives in Narragansett. “What this means is that when a stock is depressed, it takes a long time to replenish. They don’t recover from directed fishery pressure very well.”

The shark decline has become alarming enough that NMFS has begun protecting the remaining sharks. Catch limits were set in 1993, then halved in 1997. Commercial regulations now completely prohibit the killing of five species, including the famed white. Broader restrictions were issued last year but have been held up by a court challenge. But some environmentalists are no longer talking about “depleted stocks” of sharks, they are talking about extinction of species. “Sharks have been top predators for hundreds of millions of years,” says David Wilmot, director of the Ocean Wildlife Campaign, a consortium of environmental groups. “They might have only a few decades left.”

None of this comes as a surprise to Charlie Donilon. With 28 years of shark-hunting experience, the last six with his cage, he has seen the New England shark collapse firsthand. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, he regularly encountered makos, sandbar sharks, and thresher sharks, along with the occasional tiger or hammerhead. During one of his most active fishing years, a customer caught a 544-pound mako, one of the largest ever captured by a Rhode Island vessel. Another year, he tagged a 20-foot-long great white. He has a picture of that fish rising from the water to bite the bottom step of the Snappa’s dive ladder. It looks like a dog eyeing a pant cuff, except the cuff is made of bronze.

Such encounters are extremely rare nowadays. When Donilon finds sharks off the Rhode Island coast, they are almost always blue sharks, a strong-tasting species that has just begun to attract fishing pressure. If it weren’t for the surviving blues, he says, he probably wouldn’t have a shark-watching business at all. “Oh man,” Donilon says. “I used to go out 20 miles, and we had variety every day. One out of every three fish was a sandbar shark, and one out of every 20 was a mako. But I’ve seen only one mako in the last three years, and sandbar sharks—I don’t see them at all anymore. Those were good eating fish, so a commercial fishery developed, and it wiped them out.”

* * *

A midday sun has warmed the Atlantic’s undulating surface, and a breeze is starting to kick up. Donilon’s anxiety is beginning to show. Even though he has stoked his chum slick for hours, the waves are quiet. No fins crease the surface. The rope shows no tugs. “C’mon,” he says, squinting into the water. “C’mon.”

Kirkpatrick and her diving partner, Christine Strout, sit in the bow and soak up the sun. Back astern, diver F. Bruce Gerhard Jr. shares adventure stories with his scuba partner, Theodore Hotz. They have paid $165 each, and Gerhard is holding forth on past exploits: his days as an artillery officer, his dives on shipwrecks, a trip to Antarctica. Donilon listens in but peeks constantly at a dive watch the size of a silver dollar, which he has strapped to his wrist.

The striped bass carcass has hung unmolested too long, so Donilon decides to replace it with a frozen false albacore tuna, a greasier fish with rich, red meat. As he lowers the small tuna over the side, a broad swirl breaks across the surface, 60 feet or so behind the boat.

“Fin!” shouts Hotz, pointing. All heads turn. The shark, a blue perhaps six feet long, heads straight for the Snappa and then glides under the stern, paying no mind to the bloody tuna carcass as it continues on its way. Donilon leans over the rail, first to starboard and then to port. “He’s a little finicky right now,” he says, but his eyes are dancing.

The next hour brings more of the same: fins, swirls, and glimpses, but little boatside action. Charlie guesses that a single shark has followed the chum slick to the boat, and it is very wary. Then two more sharks arrive, and the big predators are suddenly at ease. They approach the Snappa for a display. Sleek as panthers, they move effortlessly through the water, banking this way and that with the slightest adjustments of their fins. They take turns investigating the swim ladder. Assuming almost vertical poses, the blues nibble the bronze, making loud grinding noises. Charlie sizes up the three of them: a 6- and a 6 1⁄2-footer, he says, each going perhaps 120 pounds, and a 7 1⁄2-footer, which he estimates at 160 pounds.

Clear water, bright skies, three sharks: Charlie’s trip is on the verge of success. He calls together his customers. “Somebody go in,” he says. “Somebody put on your gear and get in the water.”

As the group prepares its equipment, Donilon cautions the divers again. The water is 200 feet deep, and the sunlight illuminates it only about 25 feet down. “Don’t get far from the cage,” he says. “Sometimes people get comfortable with the blue sharks, and they forget there could be a white shark or a tiger hanging out of sight.”

Gerhard and Hotz are first over the side. They drop off the stern and make loud splashes. Startled, the sharks shoot out of sight, and the two men sink to about six feet and kick slowly for the cage. As they open the door and enter its sanctuary, the sharks return. Creatures of their element, they blend almost invisibly into the swells. When they pass in front of the aluminum cage, they show up in relief, instantly, like planes gliding out of the clouds.

The sharks circle the cage lazily. From his vantage point on deck, Charlie can see the scuba bubbles rising to the surface in bursts. The divers are breathing hard, excited. Donilon watches closely, but then his bait rope grows suddenly tight, and he yanks it back. One of the sharks has found the tuna, and Donilon uses the rope to lure the shark slowly toward the boat. It follows the bait, its teeth bared and tail thrashing.

Gerhard and Hotz will have 20 minutes, and then Kirkpatrick and Strout will get their turn, in a rotation that will continue as long as sharks stay nearby. For Kirkpatrick, this dive is a chance to confront her fear. This is only her second season diving, and she admits she often has sharks on her mind. “Are sharks like dogs?” she asks Donilon. “Can they sense when you’re afraid?”

Donilon tries to answer. Like many people who have dived among sharks, Donilon says that sharks rarely attack. On shore, NMFS biologist Wes Pratt agrees. “They really seem to know what they’re doing,” says Pratt. “Even though they’ve been lured in by the scent of food, they seem to know we aren’t the menu.” But out on the Snappa, Donilon tells Kirkpatrick that wild animals are wild animals, and sharks are predictable only to a point. He tells her the Snappa’s complete diving record. In all, eight divers have been bitten in his chartering career, but only one was injured, a woman who was grabbed by the seat of her wet suit as she was climbing the dive ladder. She needed 15 stitches to close the wound. Bites are bad, of course, but Donilon doesn’t dwell on them. Blue sharks are a fairly docile species with teeth about exactly as thick as a wet suit, which means their bites usually amount to the marine equivalent of a heavy gumming. The other seven bite victims had no breaks in the skin, he says.

Looking at Kirkpatrick, it is hard to tell if Donilon’s dissertation has made her feel better or worse. But she has on all of her gear—wet suit, belt, tank, mask, regulator, and knife. She looks game for the dive.

Gerhard and Hotz leave the cage. The men swim back to the boat, trailing a wake of bubbles. There are five sharks now, and the largest shows an even stronger interest in the swim ladder. After raking its teeth across the bottom rung, it drops off and then gracefully returns, rubbing its long back along it, like a big cat, until with a flick of its tail it rushes away, surprisingly fast as it disappears.

Kirkpatrick and Strout jump feetfirst into the waves and make it to the cage without a shark in sight. Hoping to bring the fish back, Donilon throws the tuna carcass far out of sight and then, hauling the rope hand over hand, brings the sharks up close to the boat.

Out here with the nearest land over the horizon, it would be easy to assume that this water is a pristine refuge from man. But now that the sharks are close enough to see clearly, such notions fade away. Four of the five have clear signs of previous human encounters. One has a long strand of mossy fishing line threaded through its gills; another drags a shorter piece of line that ends in a lime-green, squid-shaped lure the size of a dust mop. Two more have tags sticking from their backs. These are the survivors. Nobody knows how many others have been carved into steaks and sent off to the supermarket.

“It’s incredible,” Donilon says. “Hardly a virgin fish out here.”

He studies the water above the cage where the two women are watching the spectacle up close. The bubbles from their breathing gear rise in heavy bursts. For now, Donilon says, the seas still have a few blue sharks. His business is fine. But he wonders how long the sharks can last off New England. He has seen this pattern of boom, exploitation, and bust before; the cod are down to a tiny fraction of their old abundance, as are tuna and swordfish. When Donilon caught his first shark in the 1970s, New England’s marine riches seemed as if they would last forever. Now he wants the government to enact stronger shark protection before the fish that once seemed the ultimate symbol of invincibility are gone for good.

He stares down at the wild predator circling the cage. The heavy filament line hangs out of its gill. “Something’s got to happen,” he says. “Otherwise there aren’t going to be any of these things left.”