The Great Divide | Are There Mountain Lions in New England?

“Cougar truthers” are certain that the big cat is living and breeding again in New England. Wildlife experts say no. Not yet. But one day…

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanThe last catamount killed in Vermont stands under glass just inside the doors to the Vermont Historical Museum in Montpelier, a hop, skip, and a jump down the block from the statehouse. The animal was shot in the town of Barnard on Thanksgiving Day 1881 by a man named Alexander Crowell. Responding to complaints about a predator eating a local farmer’s sheep, Crowell and a small group of fellow hunters had tracked the big cat through the snow. “[The catamount’s] movements were so noiseless that Mr. Crowell found himself in this dangerous proximity before he was aware of it, and it was only by great coolness and daring that he severely wounded the animal and perhaps saved his own life,” reads a placard attached to the display case. It was his great coolness and daring (either that, or fear) that enabled Crowell to shoot the animal at a distance of “one rod only” (roughly 16½ feet), first hitting it in the leg with his shotgun, then dispatching it with a bullet to the head from a borrowed rifle.

Photo Credit : Matthew Johnson/Vermont Historical Society

There, too, is Crowell’s photograph, grainy and old: the hunter leaning against a tree stump, his head propped casually on his left hand, elbow to stump, shotgun cradled in the crook of his right arm. Bearded, bowler hat, expression impenetrable behind facial hair and the stoicism of an earlier era. The big cat on the ground before him, motionless, yet somehow still embodying that particular feline litheness, as if, with the flick of its tail, it might bound to its feet and disappear into the woods. But no. The cat is dead. The last catamount in Vermont is finally, officially, certainly dead.

The scientific name for the catamount is Puma concolor. It is also known as cougar, panther, mountain lion, and puma, though catamount is the preferred regional vernacular. Its closest living relative is the cheetah. Its distinctive feature—the one that sets it apart from other North American wild cats—is its tail, which is thick and often as long as its body. The catamount is a creature of stealth and concealment; it stalks its prey, which on the Eastern Seaboard would likely be deer, moose, porcupines, beavers, and domestic livestock. It can run at speeds of up to 50 mph. It is what wildlife biologists call an “apex carnivore,” which means it can overpower pretty much any other creature in its environment—with the exception of an armed human. All of which is to say that if Alexander Crowell wasn’t afraid on that long-ago Thanksgiving Day, he probably should have been.

———

When I accepted the assignment to write about my quest to uncover the truth regarding the existence of cougars in New England, I had little idea what I was agreeing to. Growing up in northern Vermont, I’d heard stories of sightings, though always a few steps removed from the teller—somebody’s cousin had seen a cougar cross the road on their way home from deer camp up in Canaan (or was it Coventry?), or someone’s coworker’s mother had seen one from the back porch of a summer camp back in ’07 or maybe ’08, and she’d tried to get a picture but this was before she got her first iPhone, and by the time she’d retrieved her camera from the living room, the cat was long gone. I was aware, too, of how a certain mythology surrounding the animal had taken root in Vermont’s culture and even its identity: The University of Vermont’s athletic teams, for instance, are known as the Vermont Catamounts, and their logo features a snarling cat lunging through the cleft of a “V.”

I also had the vague notion that when it comes to cougars, people tend to sort themselves into one of three camps. In the first, there are those such as myself, who’ve maybe heard a few second- or third- or fourth-hand stories as well as official denials from state agencies or professional biologists, and therefore find themselves betwixt and between, neither believing nor disbelieving.

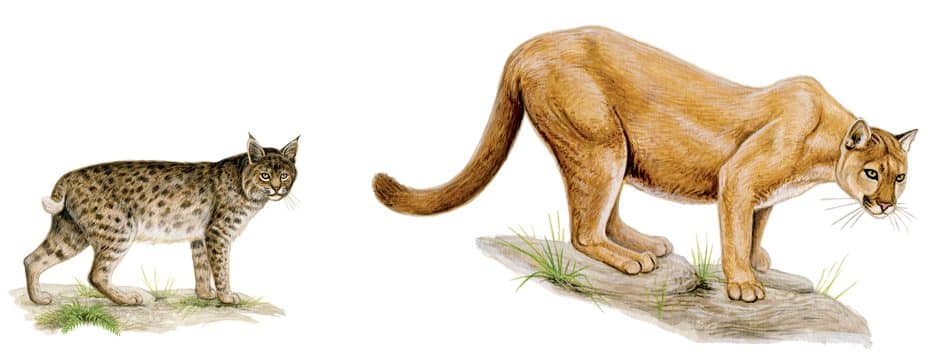

In the second camp, there are those issuing the denials, pointing to the lack of photographic evidence, or the absence of tracks, or the simple truth that many people don’t seem to know the difference between a cougar and a bobcat and a lynx and even, in some cases, a golden retriever.

Finally, in the third camp, there are the true believers—the “cougar truthers,” if you will—the men and women for whom the only logical conclusion (often reached after a significant investment of time, thought, and sometimes money) is that right here, right now, cougars live among us, feeding and breeding and rearing their young, and that suggesting otherwise is sheer ignorance, willful denial, or part of a mosaic of conspiracy. The reasons for this conspiracy vary depending upon whom you talk to, but they coalesce around the idea that wildlife agencies would be inconvenienced by the cougars’ presence, as they’d be forced to respond in ways that would tax their resources. And consider, for a moment, the concern and outright fear an official acknowledgment of such a carnivorous and predatory creature might evoke.

Photo Credit : Matt Patterson

It may not surprise you to learn that I was quite intrigued by this third group. And it was this curiosity that led me to the Old Well Tavern in Simsbury, Connecticut, at a time of day (11:30 a.m.) that does not normally find me ensconced in the dim confines of a drinking establishment. And yet there I was, on a Saturday in early November, crammed into a booth with Bo Ottmann, 48, and Bill Betty, 72, of Cougars of the Valley, the organization that Ottmann founded in 2007 to gather evidence of and alert the public to the big cats living among us.

There was a tin of American Spirit tobacco on the table (Ottmann’s), a laptop (Betty’s), a notebook (mine), and a tumbler of Bacardi and Coke (Ottmann’s again). The tavern was quiet except for some hard-rock music playing on the radio, the murmur of a handful of men at the bar, and us. Ottmann grew up and still lives just minutes from the tavern; his familiarity with the establishment was obvious (after we met in the parking lot, he led me into the building through the kitchen, greeting each of the staff by name). Betty had driven up from his home in Rhode Island. He wore red suspenders and a baseball cap. Having retired from a career at General Dynamics, he devotes many of his waking hours to cougar research, a passion he’s cultivated for nearly two decades.

“What set it off was a National Geographic special on mountain lions in California, right after my daughter and I had two encounters in my driveway,” Betty told me. His mention of these encounters was so matter-of-fact that I found myself nodding along. Two mountain lion encounters in his driveway. Of course.

“Within six weeks,” he continued, “I was getting off the plane in Jackson Hole for a national mountain lion conference. I started asking a lot of questions, and realized there’s only one explanation for the answers I was getting: They are here.”

“How many?” I asked.

“You could have 30 in Connecticut alone. You could have 50—”

“There’s probably 100 in Connecticut,” Ottmann interrupted, rolling a cigarette as he spoke.

“A hundred?” I exclaimed.

Betty was quiet, and I wondered if even he, a man who does not doubt the presence of these cats in our midst and who himself claims multiple sightings, thought Ottmann was exaggerating.

Ottmann nodded. He set down his cigarette and looked me in the eye. “You need to understand that every biologist that works for the state has a duty to deny mountain lions. But right now you’re dealing with top-notch guys. Bill and I are full-throttle. Spatz and Sue don’t want to go where we’re going.”

Betty folded his arms across his chest, where they rose and fell and rose again with his breathing.

———

The “Spatz and Sue” Ottmann referred to are Christopher Spatz and Sue Morse, two of the better-known and arguably most experienced cougar skeptics in the Northeast. Morse is a Vermont-based naturalist and the founder of Keeping Track, a nonprofit that trains people in the scientific protocols needed to detect, interpret, record, and monitor wildlife tracks and signs. Morse founded Keeping Track in the belief that getting citizens interested and engaged in wildlife will have the knock-on effect of getting them interested and engaged in how land-use decisions affect wild populations—and might provide the impetus for conservation efforts. To date, Keeping Track has helped conserve 40,000 acres in 12 states and in Quebec.

Photo Credit : Sue Morse/Keeping Track

I met with Morse at her home in Jericho. She lives near the end of a gravel road in a modest, low-slung house tucked into the flanks of the Green Mountains. There were caribou antlers mounted above the front doors, and the interior walls were covered in row upon row of books; a long table was piled high with still more books in seemingly random arrangements. There were pine cones on window sills, a well-used hatchet and a variety of animal figurines on display, and, near the television, a stack of videos including Life of a Predator and The African Lion. Morse introduced me to her cat, Allister, whom she referred to as her “portable puma.” Then she fetched me a beer.

Morse, 70, comports herself in a friendly and no-nonsense manner. She favors plaid shirts, green Dickies work pants, and hiking boots, and she chided me for shaking her hand too gently. “You wouldn’t shake hands with a man like that,” she said, and though she was smiling I could tell she was serious.

Morse has been tracking cougars for 45 years, mostly in the mountains of the West, where their existence is not in doubt. Indeed, one of her steadiest sources of funding for Keeping Track is a presentation on cougars that has been known to draw more than 500 audience members. Earlier in the year, I’d attended one of these presentations, and even in the tiny village of Woodbury, Vermont, on a stiflingly hot summer evening, nearly 100 people showed up to hear her speak and see her photographs (Morse is a magnificent wildlife photographer).

Put bluntly, Morse does not believe that New England is home to cougars. This isn’t to say she believes none of these animals has stepped foot on New England soil over the past century. Indeed, in 2011, a male cougar was hit and killed by a car in Milford, Connecticut; through its DNA, wildlife biologists were able to trace the cat back to South Dakota’s Black Hills, some 2,000 miles distant.

But other hard evidence of the big cat’s presence is elusive. In 1994, scat collected after a sighting in Craftsbury, Vermont, was found to contain cougar hair (the animals are prone to ingesting their hair while grooming), and the commissioner of the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department circulated a memo with the following line: It is possible that cougars of unknown origin may be breeding to a limited extent in Vermont. A few years later, though, the scat was retested with DNA analysis and found to be canid, rather than feline, in origin. Still more confusion ensued when a lab technician said she might have gotten some samples confused, and thus the canid result was thrown into doubt. Even in the controlled environment of a lab, the truth about Eastern cougars seems to be almost willfully eluding its seekers.

The key to Morse’s assertion can be found in the term “breeding population.” Although the fact that cougars have traveled through New England is irrefutable (a DNA-confirmed roadkill is hard to deny), Morse believes it’s unlikely that they have settled here and created a self-sustaining population. Because while male cougars eventually strike out on their own and occasionally wander far from home, females are, as Morse puts it, “hardwired” to remain close to their mother’s home range.

“The females are where it’s at,” she said. “If we end up with a population, it will be the result of a colonizer female who gets here somehow, some way, and the rest will be history.”

Photo Credit : Sue Morse/Keeping Track

———

Clearly, Puma concolor once inhabited the forests of the Northeast, although it’s difficult to say in what numbers. Records suggest that cash bounties for cougar kills were relatively common in the late 1700s and early 1800s; in the Adirondacks, a trapper named Thomas Meacham was credited with 77 cougar kills. As livestock farming came to dominate the landscape, pressure on the big cats slowly mounted on two fronts: The number of farmers wanting them dead was increasing, while the rapid transition from forest to farmland meant their habitat was shrinking. By mid-19th century, forests made up only about 30 percent of New England (it’s notable that today that number stands at approximately 80 percent, nearer to what it was when cougars thrived here).

In 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service unofficially declared the Eastern cougar extinct. Still, sightings are common. Kim Royar, a biologist at the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, told me she receives 40 to 50 reports annually, and although she believes that few, if any, are actual cougar sightings, she doesn’t dismiss the possibility that someday someone will happen upon the real deal. “I have learned one thing in my career, and that’s to never say never,” she said. “In the 37 years I’ve been working, things have changed in ways I’d never have predicted. Wildlife do really crazy things, and you just never know.”

And it’s not just Vermont. The debate rages in Maine, where the last confirmed cougar kill occurred in 1938, and in New Hampshire, where the last confirmed kill was in 1885. It continues in Connecticut, where that South Dakota cat was killed in 2011, and in Massachusetts, despite two credible reports in the past quarter century (in one case, DNA-confirmed scat; in the other, verified tracks). Nowhere in New England is the matter definitively settled.

This assessment is echoed by the aforementioned Christopher Spatz, who has been studying cougars for better than 20 years. “I don’t ever say to people, ‘That’s not what you saw.’ I say, ‘I hope you saw one,’” Spatz told me when I called him at his home in upstate New York. “People clearly aren’t lying when they say they saw a cougar; [the sighting] has a profound effect on them.”

Photo Credit : Leigh Love/Stocksy

Still, Spatz acknowledged that the word hope is very different from the word believe. “I’ve seen more field evidence in a couple of hours tracking out west than I’ve seen in 100 years on the East Coast,” he said. “One cat will leave more than 10,000 tracks per day. When a cat’s around, it’s not hard to find evidence. You don’t even have to go out and look for it.”

And so we come to the great divide over cougars in New England. On one side, there are those (as represented here by Sue Morse, Kim Royar, and Christopher Spatz, along with a number of others I spoke with) who contend that the lack of verifiable evidence is proof that the animals are not here. On the other side, there are those (as represented here by Bill Betty and Bo Ottmann, along with a number of others I spoke with) who say the overwhelming quantity of anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise. Betty, for instance, has presented on Eastern cougars more than 300 times, gathering many hundreds of sighting reports in the process. Can they really all be cases of false identification?

To Betty and Ottmann, the dominant narrative of the occasional itinerant cougar from the West is not particularly relevant to the facts on the ground. In their estimation, the presence of a breeding cougar population in New England would likely stem from our proximity to Canada, where, as they rightly point out, DNA analysis has resulted in 19 positive identifications across Quebec and New Brunswick since 2001 (although some of these were shown to be of South American lineage, suggesting escaped pets). Given the long, shared border between these provinces and New England, along with plentiful evidence that other species cross this border regularly, it seems entirely possible that cougars would also engage in international travel.

“We think they’re coming in from Canada,” Betty told me.

“I think they never left,” Ottmann piped in.

“Well, there’s no difference between Maine and New Brunswick, anyway,” said Betty. “If they’re in one, they’re in the other.”

———

If there’s a middle ground in the cougar debate, it belongs to John Harrigan, a veteran outdoorsman, newspaper reporter, and widely read syndicated columnist. Harrigan is 72 and lives just outside the northern New Hampshire town of Colebrook; he has a long, craggy face that seems almost to have molded itself after the mountainous landscape of his home state.

We met for lunch on a Sunday morning in early March, and it didn’t take long for me to understand why Harrigan is such a popular columnist. He is a consummate storyteller, and he wears on his sleeve his affection for the region and the hard-working, commonsense people who inhabit it. He’s also unafraid to take unpopular positions when he deems it necessary: Shortly before our meeting, he’d signed a petition in favor of keeping ATVs off public roads. “I’m gonna get hammered for it,” he sighed.

Photo Credit : Bruce Luetters

Harrigan’s interest in cougars was sparked in the late ’70s, after he took ownership of The Coos County Democrat and began noticing the steady influx of reported sightings. “At least once a year there’d be a story from somewhere, but I only ran the absolute best,” he told me. He soon developed a five-question litmus test: How far away were you? What time of day was it? How big was the animal? What color was it? And the clincher, What would you say was the most distinguishing feature? By now, I knew the answer to that one. “The tail,” I said. Harrigan nodded. “The tail’s gotta be there. If it’s not, you just thank the person and say good-bye.”

Forty years of reporting on New Hampshire cougar sightings has convinced Harrigan that the state is home to at least a handful of breeding animals. Part of this belief is rooted in his journalistic experience, which across the decades has cultivated his nose for sincerity. But perhaps an even larger portion is the product of his enduring faith in the men and woman—loggers, hunters, trappers—whose vocations and avocations have instilled in them a deep familiarity with wild places and the creatures who inhabit them. Because he lives among them, Harrigan understands that no one knows the woods better. And so when they come to him with a sighting, he’s prepared to believe. So long as the tail’s there, that is.

“I have no choice but to take this seriously,” he told me. “It’s not my call. If these people say they saw something, I’m going to listen.”

———

If there’s one thing people on all sides of the debate can agree on, it’s that a breeding population of cougars is essential to the overall health of New England’s ecosystems, which currently lack an apex predator. The region’s top predator, the coyote, is classified by biologists as a mesopredator (a type that in New England includes skunks and raccoons), which feeds primarily on smaller animals. “We need [an apex] predator back on the land,” Sue Morse told me. “If these animals are not in the habitat, what we see is an overabundance of herbivores.”

The ecologist John Laundre, who has spent 35 years studying cougars, concurs. He coined the term “landscape of fear” to describe the relationship between predator and prey in the wild. “We’re arrogant if we think we’re the only species that makes decisions based on fear,” he told me when I called him at his home in Oregon. “Fear is actually one of the most powerful ecological forces we know, and it’s a really important management tool.”

According to Laundre, the problems caused by a relatively fear-free ecosystem are not always obvious, in part because they can take decades to fully manifest. “For instance, a favorite food for deer is the seedlings of forest tree species. [An overabundance of deer] means our forests are getting older and older and not being replaced.” He also points to the influx of invasive plant species in New England as evidence of an out-of-control deer population. “The deer don’t eat the exotics, but they eat the competitors. They set the stage for the exotics to move in, and this has a huge impact on our ecology,” he said. “We need cougars and we need wolves back in the Northeast, because a landscape of fear is a well-balanced landscape.”

Perhaps, then, the ultimate question isn’t whether cougars are among us, but rather how we can encourage them to settle here. And that’s a surprisingly complex question, because it hinges on numerous factors: policy and politics, culture and conditioning, habitat and, frankly, hubris. For who but we humans can look across the landscape and not acknowledge our role in the diminishment of cougars and the myriad ways in which we have knocked the landscape out of balance?

———

Before I departed the Old Well Tavern, Bo Ottmann offered to lead me on a walk into an adjacent stretch of woods, where, he assured me, cougars might be found. I must have looked doubtful—we were within spitting distance of a heavily trafficked road and only 12 miles from downtown Hartford—but both Ottmann and Betty told me that cougars actually prefer more populated areas, since that’s where deer tend to congregate.

We strolled across the tavern parking lot and ducked into the forest, where Ottmann maintains a portion of his $15,000 worth of wildlife recording equipment (he’s had no luck capturing a cougar on camera, though, despite more than a decade of trying). I could hear the steady rush of traffic on Route 315. There was the vaguest of trails, crisscrossed by deadfalls and a sharp-thorned bush that soon drew blood from Ottmann’s right hand. “It’s OK,” he told me. “This is part of the cougar business. [Betty] and the other guys don’t do this shit. I do this shit.”

The truth is, I was by this point dubious. Much as I liked Ottmann and Betty, and much as I found some of their evidence compelling, I was struggling to reconcile their more provocative claims with the restraint expressed by the many other experts I’d spoken with. I appreciated Ottmann and Betty’s confidence and commitment, but here I was, poking through thorny thickets behind a bar, trailing a bleeding man whose devotion to proving the presence of cougars was beginning to seem like a quixotic quest with no end.

Yet I also remembered something Sue Morse had told me months before, as we sat in her living room drinking beer and chatting cats. “If you don’t think cougars are coming to the East, think again,” she said, leaning forward for emphasis. “Because they are.”

Ottmann and I walked farther. He’d encouraged me to keep my eyes open for deer carcasses cached in the trees (according to Ottmann, cougars are fantastic climbers and are known to stash their kills high in trees), but I saw only leaf-bare branches. Besides, Ottmann had revealed that he’d been charged by a bear in this same piece of woods, and I felt conflicted about diverting my gaze from the underbrush.

After 20 minutes or so, we turned and stumbled our way back to the parking lot. We hadn’t seen a cougar, nor any evidence to suggest a cougar had traveled these woods recently. But that was OK. Bo Ottmann knew they were out there. He knew it was only a matter of time.

Interesting article, but it is really incomplete without a discussion of the legal implications of having a confirmed endangered species such as the Eastern Cougar in New England. Obviously, this is the reason why the “experts” are loathe to admit that the species is here. Honestly, leaving this out of your article would seem to perpetuate the notion that there is a conspiracy to keep us all in ignorance….

Probably because of all the hunters that would be out trying to get their “trophy” and endangering others.

The reason why “experts” won’t admit to a breeding population existing is that there is NO PROOF. Yes, of course they are here, transients. I’ve seen tracks (Downeast Maine) and others have seen them, plain as day. The real reason that “they” won’t admit that a breeding population exists, is that listing a population of endangered species would wreak ECONOMIC havoc in a number of arenas, mostly logging/forestry. The restrictions/regulations surrounding management of an endangered species is incredibly cumbersome, and would be difficult to manage. It has nothing to do with trophy hunting, public safety, etc…

I think the reason that they don’t admit it is because there is, more accurately, “no proof of a breeding pair in an area”- that is not to say that folks aren’t seeing cougars from time to time, but they usually don’t stick around an area for long and move on. I’m sure though that the evidence for cougars going g through a. Area is increasing- with trail cams, cell phones, scat sightings etc. At some point there might be enough evidence to show that a breeding pair is in an area.

We lived off of Mountain Rd in Granby, Ct for 8 years and I can say that without a doubt I am 100% sure that there are mountain lions living there. I saw on three occasions in about the same location a beautiful mtn lion with the long bushytail that curves at the end. One one occasion she had two little ones with her so their den must have been sort of closeby. We also had bobcats that we saw quite often but I am positive that these were mountain lions! They were also seen at other times by members of my family and other people in the neighborhood. They are there and thriving!!!!

Indeed! I lived in great Barrington mass and I took photos of tracks in a field in April of 2009 (and of course lost them). and with my friend Chris Christinat who lives in hartsville we saw one stalking a rabbit on her lawn about autumn of 2009. We were about 50 feet from it and it stood taller than any labrador and we watched it tail and all slink down the side of the lawn and the rabbits being surprised out of the bushes. It was definitely a cougar.

I live in Hopkinton, NH and saw one coming up from the Contoocook River one misty morning. You can’t mistake the long tail. They are much larger than bobcat and lynx, young adults can still have spots too. Our hunter friend was hunting in central NH when they came upon an adult deer carcass way up in a tree. A mountain lion was responsible for that too. There are many “officials” in denial up here, but we know what we saw and there are too many sightings by the local folks to be ignored.

I’m not surprised that various state officers deny the presence of cougars in new England. Several years ago, I saw what was definitely a cougar walking along a street. I reported it to Connecticut DEEP, only to be told there are no cougars in Connecticut. I wasn’t the only one to see the big cat. The cougar and the state’s refusal to admit it was here made the local paper. Photos of the cat did nothing to convince DEEP the cat was here. They denied it until a cougar was hit as it tried to cross the very busy Merritt Parkway. They are most definitely here.

Well, I KNOW there was at least one mountain lion in NE because years ago (maybe 35 or so) I lived in Longmeadow, MA. One summer I saw what I assumed was the same cougar several different times in my neighborhood which was near a long strip of woods along I 91 and used to be a large open field across the road from our home. One day I most certainly watched him/her being chased up and down our chain link fence by a neighbor’s large dog who was barking insanely and couldn’t quite catch the cougar, who finally made it away from the fence to escape the determined dog who’d had him trapped up against it. He/she was UNMISTAKEABLY a mountain lion: stretched out straight, long tail straight out behind him, golden/beigey color, and smallish head, little ears. I was just amazed as I watched this scene in my own back yard. Then saw him a few more times from further away across the road and along the edge sometimes of the woods. Beautiful animal. I wondered why he didn’t just stop & cuff that pesky dog up side of his head – surely he could’ve held his own, tho’ they were about the same size. I’ve never forgotten that and told it to many folks over the years, most of whom, I must say, thought I was hallucinating I guess – but, it/he/she was a fact in Longmeadow, MA that summer long ago.

With all the thousands of trail cameras in the woods of New England, one would think that there would be at least one picture taken of a catamount.

I saw a cougar in Wolfeboro NH crossing / running across 28 ; close call between myself and a car traveling in the opposite direction over 12 years ago . Concerned for people / pets and a school just down the street, stopped to report the sighting where dispatch told me that if I did not have proof they would not respond. Others have seen cougar in neighboring towns . I also know of someone who said they showed F&G a photo of one from a game camera in NH. They are here & ..just a matter of time with photo or kill on a highway/road.

Yes I have seen several pictures on game cameras from people in Massachusetts in Central and western Mass that do have mountain lions on their game camera so please don’t be ignorant

I’ve attended talks with Sue Morse. She IS, perhaps, the most knowledgeable and experienced person in this arena and I listened intently to her presentation (Richmond, VT 2018). However, when I asked the room of 200 or so people how many believe they had seen a mountain lion/cougar/puma/catamount, hands shot up all around the room – about 25% of those present.

Dismissing most of the sightings as probable bobcats, Morse asserted that the scientific evidence has not been proven. That’s a reasonable assertion.

Still, there are those of us who know what we’ve seen. My encounter was in Middlesex, VT along the river road (Route 2) just below I89. I had been the first vehicle in a line held up by one lane traffic on a bridge reconstruction. So, traffic had been slowed from both ends for a good 3-5 minutes. As I turned a corner going north toward Waterbury, I saw the cat come up from the cornfield, saunter across the highway, turn and look in my direction and then amble off into the brush. In my mind, I went through all the “nots”. It’s not a bear, not a dog, not a deer, not a bobcat. THAT is a mountain lion! How did I know? Length of body. Height. Distinguished by a boxy head, big paws and a VERY long tail. I kept trying to make it be something else because I was shocked that I was, indeed, watching a mountain lion pass in front of me. But, yes, that’s exactly what it was. Beautiful creature. They’re here.

I lived in Woodstock, CT in 2005/2006. I saw an adult cougar/catamount twice within a two week period. The first time was in the yard which was surrounded by woods. I was outdoor with my two pugs and quickly scooped them up and brought them in the house. The second occasion was on the way to work when I saw the cougar/catamount crossing Route 44.

I did call in a report to CT DEP and they basically dismissed my narrative questioning whether I made a mistake confusing the animal I saw with a bobcat or fisher cat. Neither resemble a cougar!

I was deer hunting with my father, it was in the fall about 7 years ago, in Barre Ma towards the Templeton Ma lines. I was tracking some deer tracks and I came to a promising deer run with a lot of deer scat on the ground when I noticed a cat track amongst the sign. I knew it was a cat track because the tracks were in a straight line and no signs of claws like you would see with a coyote track. I started to get nervous so I was scanning the area low and high in the trees. I came across a dead adult deer carcass high up in an oak tree. I knew it had to have been from a mountain lion… I’ve seen bobcats and their tracks and from the size of the deer carcass I’m convinced there are mountain lions amongst us in Massachusetts!

I saw one about 10 years ago, on our road. It was huge! It jumped 28 feet across the road. My neighbors have seen several over the last 15-20 years.

There are no breeding cougars in New England and we do not need any.

Just like we don’t need any slimy humans on earth period. People like you are the problem and cause of extinctions.

I thought I saw signs posted in Pawling’ NY about 8 years ago, that DEC released a pair to control deer population,mane several people have seen them in Wingdale, NY

I’ve heard this as well

Early spring 2019 I caught a glimpse of one entering over grown brush on the side of the road very very early in the morning. I mentioned this to a neighbor who spotted one a few miles away. My assumption is it was the same animal. I also had a coworker report a similar experience around the same time. No need since so we guess it has moved on from the northeast corner of Connecticut.

We really must establish first that these beautiful animals SHOULD be in every state that was once THEIR habitat. Cougars, Lynx, Bobcats, Wolves, Bears etc were and are a

vital part of this countries ecosystem. It seems humans just can’t resist destroying these animals and either don’t realize or don’t care what damage we have done to our natural environment over the centuries. Where I live bears, wolves cougars etc roamed freely and now sadly if one of those apex predators is spotted our DNR will usually destroy it. Humans and wildlife MUST learn to live along side each other and we MUST learn to respect nature.

Don’t forget, south Texas also used to home to two other species of cats – ocelots and jaguarundis. Now, ocelots are critically endangered and jaguarundis might be completely gone.

In fact, jaguars used to be native to south Texas, as well!

Warren ,Ma early morning having my coffee on my front steps and noticed about 50 feet across the Road something coming out of the trail as it did it looked out at the road and turned around as it did I could see that it was a mountain lion ! If seen bobcats and moose and coyotes and coy dogs ! This was as clear as day had a long tail and long body I was thinking someone’s pet was on the loose or escaped form a zoo !! Stupid me grabbed my camera and a stick as to protect myself ( yes stupid idea as I could stop this thing from attacking me lol. As I walked thru the beginning of the trail I spooked a deer and heard this awful screech – and slowly backed out of there .. I heard from Neighbors that they have been sighting from the mass pike which runs along this area but also very close to Quabbin! I will never forget what I saw! So yes they are here and not to sure why they don’t admit to them being around !

Jason

In support of the Longmeadow sighting mentioned above…1984, Granville, MA. Snowy winter AM just before us neighbor kids were heading to catch the bus, we (myself, my dad and neighbor) all watched a large cat cross the yard and leave huge prints and a distinct tail drag mark in the snow! Was INCREDIBLE! I now live in Boulder, CO where we have regular sightings….same animal as 35 yrs ago…hands down

My daughter and I were driving north in West Granby, near the Simsbury, Ct. line just after lunch one summer day a few years ago. My daughter said to me “that’s the biggest cat I’ve ever seen”. As I looked at my daughter and then turned to follow the direction she was looking, I saw the animal in my side mirror. I only saw the back side, but he was huge. He was a dark butterscotch color, very tall and lanky (taller and thinner than a really big German Shepard) and that tail. His Tail was very long almost touching the ground and as thick as velvet rope.

My mother always said she saw one across the street from our house one night in the late 50’s early 60’s. She said it jumped up on the neighbors stone wall which was pretty high and walked across it. The one thing that jumped out at her… the tail. She said it was long and thick. The police and everyone else just shook their heads… but she to her dying breath said she saw a mountain lion in Lexington MA.

Mr. Betty and Mr.Ottoman’s passion and efforts are impressive. However, many of their claims—especially Mr. Betty’s contention of roughly a dozen personal sightings in New England—are hard to take seriously.

This is always been a debate however as someone who is an avid Outdoorsman I can say with certainty I know of at least 12 people that have personal accounts of seeing mountain lion in Central and Western Massachusetts. Not a bobcat 100% mountain lion and anybody that tries to think a bobcat as any resemblance to a mountain lion clearly has no idea about wildlife there are a lot of false reports because of this however they are without a doubt in part of New England and fish and game has as usual covered up despite coming out and following mountain lion tracks in the snow through the woods in Central Mass and finding a deer carcass 20 feet up in a tree and said to the landowner yep you probably have a mountain lion passing through and asked for the homeowner not to speak much about it furthermore DNA confirmation of a horse that was attacked in Petersham Massachusetts in the last several years and also the Quabbin Reservoir DNA were mountain lion without a doubt they are here. Regarding a breeding population that is the unknown.

I saw one yesterday in Windsor Cty Vermont. 5-7 yards from me. I had been foraging up in an area that is rocky. When I came out, the cat appeared in front of me coming up a rise (incredibly close to some ski condos). I think I may have pissed her off since I was up in that area X2 this week. Anyway I got to see that set of eyes way closer than I ever wanted, by the time my hand got on my pistol she was gone. I wasn’t planning to shoot her unless she moved in my direction. Had trouble sleeping last night cause that was to close and I think she may have stalked me from where I was in the woods.

About six years ago, my mother and step-father were traveling some back roads down to New Boston, NH to visit my sister where she lived in an extended care facility. It was a bright sunny summer day. My stepfather had been a hunter and was no stranger to seeing animals in the woods and countryside, so when they came up over a knoll in the road and saw a large cat looking at them, he saw the face and thought, “bobcat”…until they then saw the rest of the animal’s body: huge, beautifully tawny colored, and in possession of what my mother described as a very long tail, “that was as thick as my wrist”. As they watched in amazement, the cat casually moved off and disappeared into the surrounding woods. When I shared their story with the staff at the center where my sister lived, I expected surprise and interested. Instead, the responsne I heard were nonchalant, “Oh, yes, lots of people have seen that mountain lion around here; pretty isn’t it?”.

Probably are lions in western NC, too. I have heard several accounts from sober, sane, intelligent people who have seen them (especially a latre, good friend who was a very competent spokesman and hunter.). Our wildlife biologists and enforcement agents are mostly political bureaucrats who don’t often venture more than 100yards from the truck. Somebody in the NC Legislature believes, because lions are now protected by law. Check out “4 Seconds Until Impact” by Bruce Hemming, or Cat Urbigkit’s books about predator attacks in “unlikely” places . Respect predators, protect them but don’t worship or try to hug them! Wildlife is unpredictable (and several people go missing in wild areas, parks especially, every year -Probably not because of alien abduction).

I have pictures of tracks around my car and up to the back steps of my deck in Arkville, NY . My parent’s friend in Deposit, NY, posted a young catamount sitting on the front porch on Facebook.

They are here in the Catskill Mountains, so named for the magnificent felines.

Whenever I drive up and through my home state of Vermont, I look into the hills that surround me that have no sign of development for miles and miles. It is hard for me to believe that the big cats haven’t found plenty of space to roam without regular detection.

Saw one on old mountain rd Peterborough N.H. a few years ago on my property followed it and ran to get my camera have a photo but in distance by time got it was amazing animal t Metcalf

I saw a Mountain Lion in 2007 in Northfield, MA at the junctions of Rtes 10 and 63. I was driving to work in Greenfield heading south on 10 and had just taken a right hand turn at the junction when the big cat crossed the road in front of me. No doubt of what it was; size, color and recognizable tail. Of course no dash cam or accessible phone camera at the time!

There was one photographed on a porch in Greenwich, CT, looking in the patio window that made national news a decade ago. ‘Experts’ need to see the body to dismiss their prejudices. Recall a few years back, a guy in a kayak off Horseneck Beach in Westport, MA, was tracked by a large fin. An ‘expert’ said it was probably a basking shark. The ‘expert’ opinion held up until a man was killed by a Great White not too far away.

My husband and where riding our Motorcycle down Rte 110 near Milan NH

my husband tapped my leg and asked what is that crossing the road It was a Cougar tan in color long tail which had a slight curl upward .I wish I had my camera to prove it but I know We saw it.

Several years ago, I was bicycling with a buddy up Quabbin Reservoir’s Administration Rd. on route to stone tower on Quabbin Hill. We witnessed a mountain lion stalking a herd of deer. There was no mistake. When we reached tower, a ranger arrived in a pickup. We told him what we saw, and he confirmed other sightings on the property. When he suggested we retrace our route, past lion, to see a sow bear with cubs, we headed in the opposite direction.

my father was recently trout fishing in central Mass. near Greenfield with an experienced guide that he’d worked with several times. The guide told him earlier in the summer he and a couple clients had watched a moutain lion come down to the bank of the Deerfield River just upstream and take a small deer, fawn, drag it into the woods and it kill it, they could hear the screams of the deer as the cougar finished the job.

This guy was very intelligent, he had abandoned a professional career to pursue his dream of guiding. He and his clients were 100% sure of what they saw, and it’s very difficult to imagine any other animal being mistaken for a cougar in this case. Wildlife biologists, as professional scientists, require a higher level of documentation and proof. They were also reluctant to certify that turkey and moose had returned the Quabin reservoir lands for many years after locals reported seeing them. Friends that go backcountry skiing in Vermont have reported seeing tracks to me many times and I have seen pictures of the pawprints myself that look overwheming like a mountain lion.

I just heard from a fellow college student of a siting in Greenfield last fall and two in Colrain this spring.

I have not had the pleasure of seeing one, but have heard credible reports of them in Western Mass. Now that USFW has declared them extinct, why not formally reintroduce them. I’ve heard some biologists say it is not a distinct subspecies. And DNA analysis shows us that felis concolor is genetically the same across the US…I think it is irrelevant, but interesting. If this habitat can support them, it should. Apex predators like the cougar and wolf make for a healthier ecosystem. Public opinion surveys show many more would support reintroduction, than oppose. Even in areas of high cougar density, the there are far more attacks on humans by domesticated dogs or deer/car collision fatalities than those due to cougar attack. It is healthy to have respect and caution, but fear shouldn’t drive ecological decision making. I think of Aldo Leopold’s Thinking Like a Mountain essay about how deer decimated the forests and died of starvation because of human’s incessant desire to kill. Defender’s of Wildlife developed funding to support wolf predation on cattle which I believe worked. The discussion of whether federal lands should be a place to subsidize cattle ranching is another question. We clearly have migratory male cougars coming through. Female’s ranges are much smaller so it will take reintroduction or a few savvy wildlife biologist in the dead of night. But, I think with education and planning, we should reintroduce wolves and cougar in the Northeast. They have a right to exist here and they contribute to healthier prey species. There is no shortage of deer for all apex predators whether they are canine, feline, or human.

Even though the “experts” say there aren’t any mountain lions in CT, there are. I live in New Milford and I saw one crossing the road in front of me when I stopped to get my mail from my mailbox. Big kitty.

What are the chances of wolves coming back to Vermont?

In Ny a few years ago, several people over a week’s time reported seeing a puma- in different parts of the town area- I doubt it stuck around as haven’t heard another report since then- they all described the same thing- including the long tail- and a couple of them saw it close enough to realize it was no bobcat or even lynx, which also are very rare in the area. (NY reintroduced lynx a number of years ago- they didn’t stick around and one was killed on the road as far away as Massachusetts. I haven’t heard of any lynx sightings for many years, but don’t get around as much as I used to, so who knows?). The state of course denied that they are here, but I suspect they either came down from Canada, or were driven down by older more dominant cougars, or they came from out west- pretty sure they aren’t residing here. I personally saw a ledge along the Northway during winter that was about 30 feet high where an animal’s tracks came down from the woods to the edge of the ledge, and it dropped to the ground and followed the Northway for a distance before going back into the treeline. Not sure what cou,d have made that leap, mighta been bobcat or,lynx- I don’t know- it certainly wasn’t deer, and I doubt it was coyote, but who knows? Maybe it was a rabid animal- but whatever it was, it had a long bounding stride, then stepped normally for a bit. I wish I could have stopped to see what made the tracks. Our neck,of the woods there are lots of hunters, and they hunt during the snow season, but haven’t heard any reports of tracks or sightings for awhile.