The University of Vermont’s Morgan Horse Farm | The Horse That Changed America

UVM’s Morgan Horse Farm shows how its namesake breed is far more than a storybook legend.

Farm manager Kimberly Demars with Havana, one of the Morgan broodmares.

Photo Credit : Heather Marcus

Photo Credit : Heather Marcus

There are any number of ways to wind up at the magisterial white barn at the University of Vermont’s Morgan Horse Farm in Weybridge, Vermont, a 127-acre property tucked between the Green Mountains and the silver trough of Lake Champlain.

If you’re a horse, chances are you were born here, one of many offspring in the longest continuous breeding program of Morgans in the nation, one devoted to perpetuating the traits of a horse that changed America. You are the descendant of a not-so-promising colt that begat a world-famous breed.

If you’re 25-year-old equine specialist Kim Demars, you were first a kid who longed for a Morgan horse, and now, thanks to mysterious providence, you’re helping ensure the future of the breed.

But let’s say you’re one of the farm’s 10,000 annual visitors, which means you followed increasingly remote roads before finally turning up Battell Drive, where a pair of weeping willows drape like horses’ manes, to reach this historic farm.

So you’ve parked your car on this June morning, and now you’re strolling toward this stately barn, with its fancy cornices and cupola, at the end of a sprawling lawn. It’s serene and silent. You may be wondering, Is anyone here? but inside it’s a veritable equine hive: home to 40 horses, more if you count the ones in vitro.

Photo Credit : Heather Marcus

Wander into the vestibule, festooned with ribbons and photographs of dark-eyed champions, and you’ll meet the person staffing the gift shop. Just a hay bale’s toss away from the cash register there’s a long hall of box stalls, each with a 1,000-pound Morgan watching your approach. Down one floor you’ll find more stalls, and tucked into a corner there’s a chestnut mare with bright white socks standing in the crossties as an apprentice brushes her flanks, preparing her to meet some visitors.

Photo Credit : Heather Marcus

Beyond is the indoor riding area, where a horse the color of molasses trots in earnest circles around a woman with her blond hair pulled into a ballerina bun—this is Demars, the farm manager. Within the hour they’ll clear out so a stallion can arrive and occupy the area for breeding purposes. His material will be examined and packed into containers in a nearby laboratory: It’s a side room no bigger than a pantry, but it contains everything necessary to perpetuate the genetics of a horse that never lived in a barn as grand as this one.

—

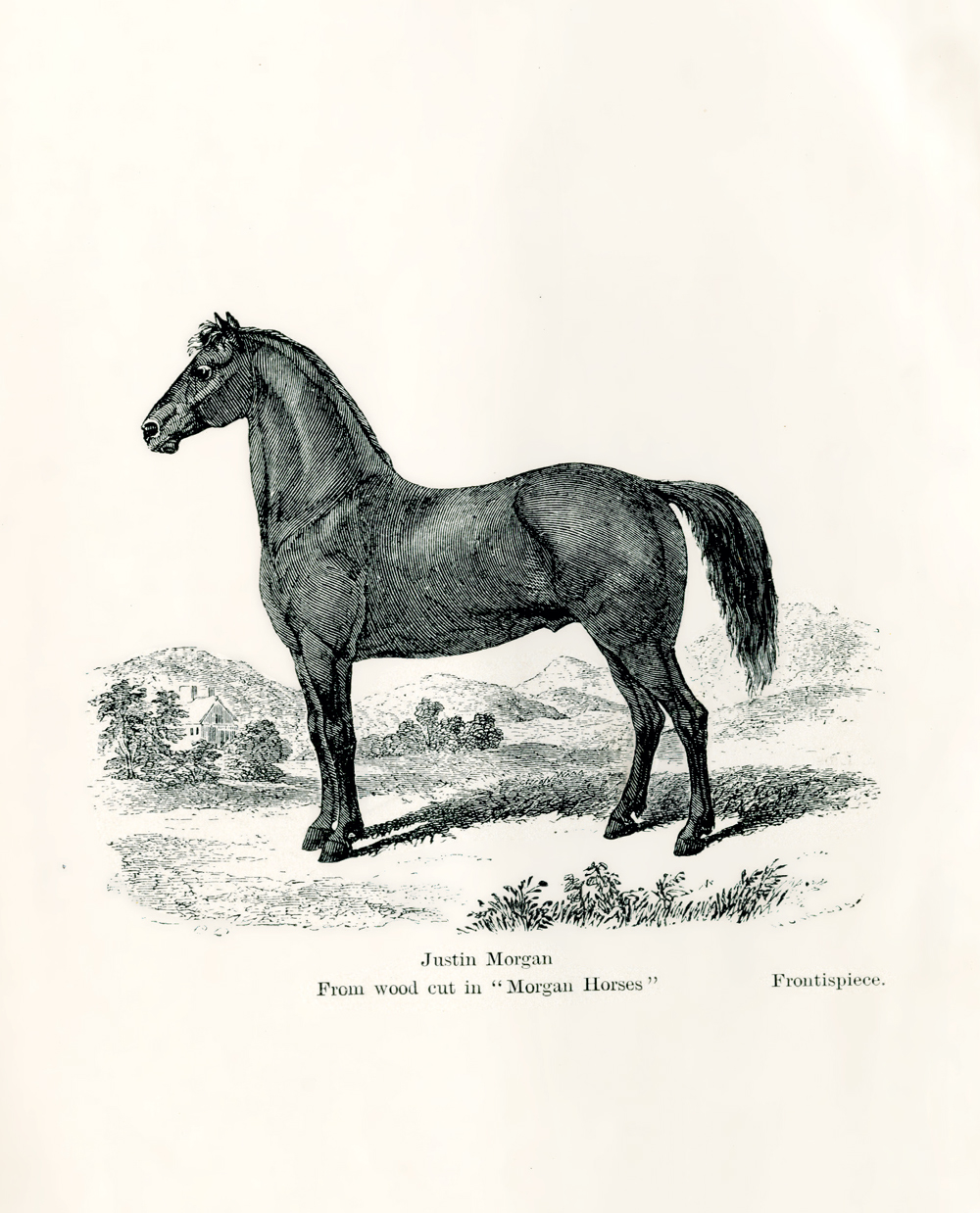

The Morgan breed originated with Justin Morgan, a Vermont music teacher who in 1792 fortuitously accepted a debt repayment in the form of two horses—a stallion and a colt—instead of cash. In the days when almost everyone and everything moved around on or behind a horse, Morgan’s colt, named Figure, became legendary.

“This is the story of a common, ordinary little work horse who turned out to be the father of a famous family of American horses” is how Marguerite Henry begins Justin Morgan Had a Horse, the book published in 1945 that won a Newberry Honor award and a lot of youngsters’ hearts. Though small in size—reportedly 14 hands and about 900 pounds—Figure accomplished astonishing feats. He cleared timber and hauled stones to establish fields and pastures throughout north-central Vermont. In 1795 (or thereabouts), he raced against two horses in Brookfield—one after the other—and won both times. Almost a decade later, he won a pulling contest in St. Johnsbury. Then, in July 1817, Figure bore President Monroe through the streets of Montpelier—leaving little doubt as to why the breed later became Vermont’s state animal, as “it could outdraw, outrun, and outtrot any other horse.”

Justin Morgan kept his “rugged little stallion” for only a handful of years; he advertised his breeding services, leased him out as a workhorse, and then sold him. Figure went on to have 11 owners during his lifetime. Even so, the horse came to be known by Morgan’s name, as did the breed, secured by Figure’s accomplished progeny.

In a lithograph portrait of Justin Morgan, his eyeglasses perch on his forehead and his face registers a look of sober surprise, as if he’d just heard, Hey, mister, long after you’re gone, people will utter your name daily, because it will become the moniker for a breed that will carry thousands of men through the coming wars, haul families out West, and will even set a record as the fastest trotter in the world.

And all because one late summer day Justin Morgan went out to collect a debt and brought that little colt home.

—

Two hundred years later, Kim Demars’s parents brought a little filly home, a Morgan named Tanner. Tanner was 4 and feisty; Kim was 7. They matured together. Then Kim left for college, and Tanner went to another farm. So Kim assumed that the Morgan portion of her life was over. But then one day after college, as she was working as a receptionist, the director of the Morgan Horse Farm, Steve Davis, phoned asking her to stop by to chat about a job opportunity. Did that just happen? she asked herself afterward. Soon, she was learning to breed Morgans at a 19th-century farm founded by Colonel Joseph Battell, a man smitten with the breed.

What horseman wouldn’t be? Figure’s descendants had accompanied prospectors to California for the Gold Rush in 1848 and hustled mail across the dangerous West with the Pony Express. They had served both a Confederate general and a Union general during the Civil War, and after the war they were chosen for the U.S. Cavalry.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of the Vermont Historical Society

They inspired Battell, a bachelor philanthropist from Middlebury, who commissioned this handsome facility to house some of the finest Morgans as well as established the Morgan Horse Registry. In volume I of his American Stallion Register he wrote, “When such men … who had progressive ideas … to improving the horse stock of the country have died, they have left no sons who were interested to carry out their ideas, hence their choice animals have been dispersed and their efforts in measure been lost.” To counteract this, when Battell died in 1907 he left his barn and the Morgan-stocked property to the U.S. government, which turned it into the cavalry remount station Battell had envisioned.

“With a government breeding establishment managed by honest competent men who are practical horsemen, and who have made the subject of heredity careful study, it will be different,” he wrote. “When one set of men drop out, others will be found who will take their places and continue to carry out the original idea, generation after generation.”

—

In 2013, a few months into her new job, Demars bred her first mare. Donning a long plastic glove, she administered a whisker-thin cylinder containing genetics of a carefully chosen stallion into the mare, thereby accomplishing the risk-free equivalent of a romp in the hay. Then she waited as first-cut hay was baled and stacked away … as zinnias were planted and clapboards painted … as busloads of visitors toured the premises … as geldings trotted in circles, preparing for horse shows … as second-cut hay was baled and stored … as the older foals were weaned … as water buckets froze and Battell Drive had to be salted and plowed. Then finally, 330 days later, the mare gave birth.

Photo Credit : Heather Marcus

In that late April chill, Demars watched her first foal—a filly—blink her wide, sober eyes; unfold her jumble of slick limbs; then rock herself upright, and stand. Whereas many of the farm’s Morgans have dark coats, this foal’s was a bright chestnut, and above her hind hoofs were white socks. Over the following months and years, visitors praised the distinct beauty of the filly, who was named Valencia. “She was true to the Morgan type,” explains Margot Smithson, operations coordinator at the farm. “Her parts all fit together; her face was so pretty, and as far as her temperament was concerned, she was as kind and sweet as they come.” In this way, Valencia embodied the qualities of her famous ancestor, Figure.

The U.S. government concluded its remount program in 1951—by which point automotive technology had made horses nearly obsolete—and subsequently the property was acquired by the University of Vermont. Over the years a series of “honest competent men” have continued the Morgan breeding program on the premises, financing the enterprise through selling horses, offering breeding services, and welcoming tourism.

More recently, women have assumed leadership roles at the farm. On this June day Demars and her apprentice, Hannah Bevilacqua, are working inside the lab. As Bevilacqua analyzes a stallion’s semen under the microscope, Demars assembles the containers for filling breeding dosages. For the past six weeks they’ve attended the deliveries of eight foals. As well, they’ve been breeding other mares to carry on the next generation.

Photo Credit : Heather Marcus

In a nearby corral, the newest horses, some just a month old, nuzzle and bump against their mothers. The colts are alert and inquisitive, adhering to the mares like mischievous shadows. One nibbles your bare elbow, and then sniffs opportunistically at your wrist. Then it reaches out to nip another foal, reminding you of backseat shenanigans between siblings.

Just before noon, a couple arrives at the farm. A month ago, they took the five-dollar tour that begins outside by the bronze statue of Figure. By the time they steered their car back down Battell Drive, they, too, were smitten with the breed. Today they are hoping to meet a special horse, one they can ride across the open fields of Vermont.

After greeting the couple in the barn’s vestibule, Demars leads them past the preserved skeleton of Black Hawk, a famous Morgan trotter, and the black-and-white photos of prize-winning government Morgans. She takes them down the corridor of Battell’s beautiful barn to the box stall at the end, where she stops, her hand on the latch of the stall. Then she slides open the door to reveal a 5-year-old mare with a shiny chestnut coat and pretty white socks standing patiently. “This,” she says, “is Valencia.”

University of Vermont’s Morgan Horse Farm Visiting hours: 9 a.m.–4 p.m. daily, May 1–October 31 Tickets: $5 adults, $4 teens, $2 kids (free for ages 5 and younger) Address: 74 Battell Dr., Weybridge, VT For more information: 802-388-2011; uvm.edu/morgan

Julia Shipley

Contributing editor Julia Shipley’s stories celebrate New Englanders’ enduring connection to place. Her long-form lyric essay, “Adam’s Mark,” was selected as one of the Boston Globes Best New England Books of 2014.

More by Julia Shipley