The Haunting Case Of Orville Gibson

Yankee Classic: December 1987 If an entire town can be said to share one ghost, then Newbury, Vermont, has held clear title to Orville Gibson ever since he disappeared 30 years ago this month. It wasn’t until 85 days after he vanished that the town, and then the nation, learned the grim fate of Newbury farmer […]

Yankee Classic: December 1987

If an entire town can be said to share one ghost, then Newbury, Vermont, has held clear title to Orville Gibson ever since he disappeared 30 years ago this month. It wasn’t until 85 days after he vanished that the town, and then the nation, learned the grim fate of Newbury farmer Orville Gibson.

Here how the story happened

Orville Gibson rose from bed at his usual hour of 3:30 on the morning of December 31, 1957. It was a brittle morning along a picturesque stretch of the Connecticut River known as the Oxbow at the Lower Coos, in upper Vermont. The temperature outside Gibson’s modest farmhouse, which was set just a mile from the outskirts of the town of Newbury, was around freezing.

Gibson, a laconic, big-framed man, one of the area’s most prosperous dairy farmers, dressed himself warmly, checked the fire in his furnace, and drank some coffee. He put on his wool cap and boots and left the house carrying a white metal lard pail—he used the pail to bring fresh milk back to the house. Just before 4 a.m., Gibson walked across the state highway that divided his property and entered the big wooden barn with its distinctive twin cupolas. The new day’s milking was about to commence. He switched on the barn’s lights.

Ordie “Hoot” Gibson, as he was known in Newbury, was not seen again for almost three months.

It was more or less left to two Vermont state troopers posted in that part of Orange County to try to solve the mystery. Their names were William Graham and Lawrence Washburn, and they made a curious team. Graham was tall and lanky, a bachelor who loved to hunt and fish. Washburn was shorter and thickset, a father of three, the team’s jokester, and an avid cribbage player. “Washburn was the thinker,” says Graham, “and I was the plodder. We somehow got things done that way.”

When Orville Gibson disappeared, the tandem was working eastern Orange County and parts of two neighboring counties six days a week, 12-hour shifts, with one man on days and the other on nights. They normally investigated things like breaking-and-entering complaints, thefts, juvenile vandalism. They served summonses and made arrests for deer jacking and drunken driving. Every now and then they also looked into what was known as an “untimely death.” Most of these deaths were suicides, and most of them involved distressed farmers.

Evalyn Gibson called the State Police outpost in Newbury at about 6:30 the morning her husband vanished. Larry Washburn was just coming off the night shift and was about to hand the load over to Graham, who came on at eight.Instead, he went down the road to try to comfort the worried woman until Graham could get there.

When Graham arrived, the two troopers questioned Evalyn Gibson and then examined the barn. Gibson’s lard pail lay on the floor, badly dented. They found fresh scuff marks on the floor and other marks that looked as if a large bag of grain had been dragged across the floor and down a 30-foot incline to the yard. The trail stopped there. A mile away in Newbury, a handsome river town of about 1,400 souls, the mystery of Orville Gibson’s disappearance was big news even before the troopers set foot on the Gibson property.

“By nine that morning, I’d say,” remembers Graham, “everybody in town knew about it and either had a theory and was talking a mile a minute or else wasn’t talking about it at all, period.” The physical evidence suggested that someone—possibly several people—had kidnapped Orville Gibson.

The question the troopers asked themselves was why. “But even then,” said Washburn, “we didn’t have to think about it too much to come up with a possible motive.”

A few days before the disappearance, Washburn had appeared at the Gibson farm to serve Orville Gibson with a breach-of-peace summons, relating to an altercation he’d had with his hired man, Eri Martin, the day before. The story was all over Newbury that Orville Gibson had severely beaten the much smaller hired man for having accidentally spilled two cans of milk. Martin was said to be in terrible shape, with broken ribs and a bruised kidney. One account placed him in the hospital, near death. Very little of this village-pump information was true. Martin was alive and doing well, save for a few bruised ribs and a lingering hangover.

Even so, the troopers now had at least two possibilities. Suicide had to be given serious consideration because friends and family members of the missing man admitted he had been upset by the alleged beating and the summons. And then there was the possibility that someone had decided to mete out a little revenge on Orville Gibson.

That theory was strengthened considerably within hours of the disappearance when a man named Freeman Placey, the brother-in-law of Orville Gibson, went scouting about on his own for clues and came up with something interesting on the town’s old iron bridge. He went to the Gibson farm and took Washburn back to the spot and showed him a small amount of silage—a mix of hay and feed. Every farmer’s silage is as distinctive as his own hand, and Placey, a farmer himself, maintained that the silage on the bridge had come from Gibson’s barn.

Graham and Washburn spent the subsequent days dragging the frigid black waters of the Connecticut River, interviewing neighbors of the missing man, and conducting nighttime roadblocks. After the river yielded no body, they picked up shovels and spent hours digging through grain bins and manure piles at the Gibson farm and other places in the county. Someone in the Placey family consulted a clairvoyant living in Plainfield, Vermont, and the woman “saw” Orville Gibson’s body “in a damp place, a white house on a hill.” Graham and Washburn followed it up, visiting essentially every farm in the county. “We searched every place,” said Graham. “It was crazy, but we had to check it out. Do you know how many white farms there are on hills in Vermont?”

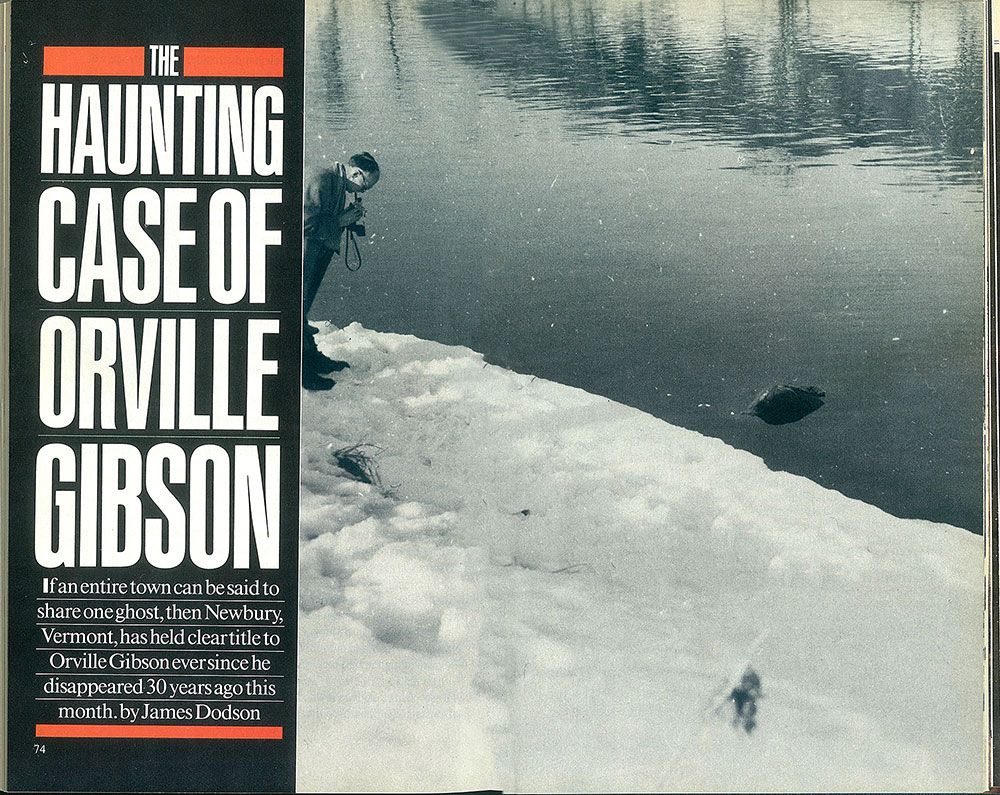

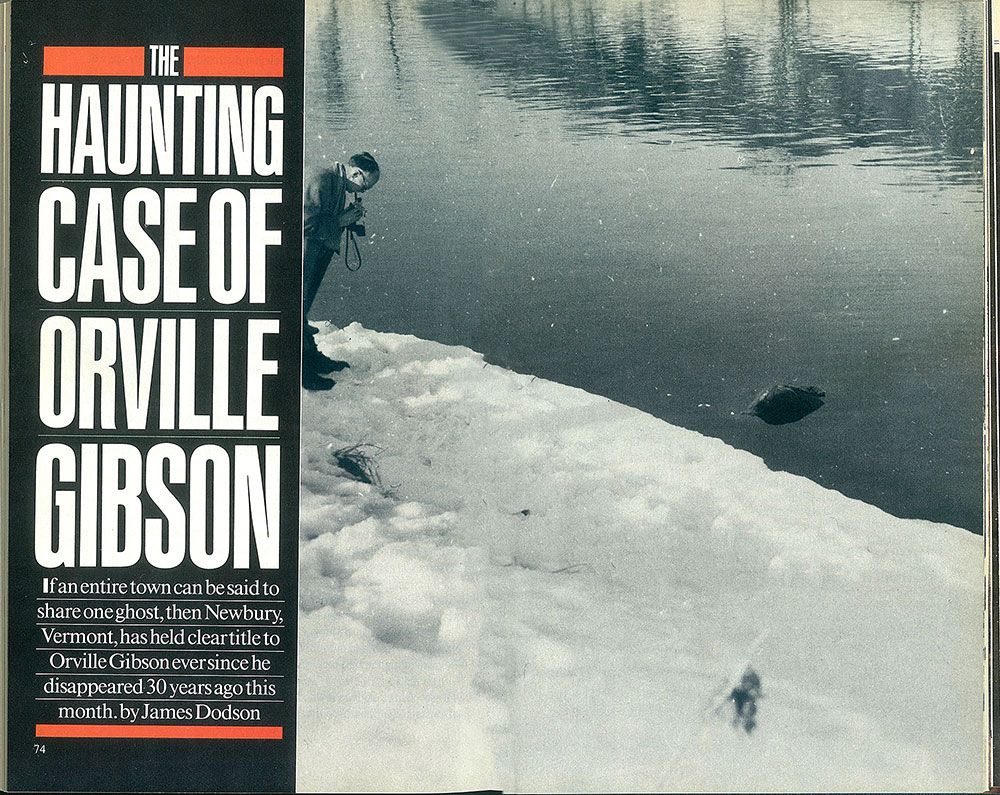

One morning in March, 85 days after Gibson disappeared, Graham suggested to Washburn that they take a little boat ride. The weather was clearing and Graham had been studying a book on forensics. By the book’s calculations involving water temperature and the gases of a decomposing body, Graham had figured Orville Gibson’s body might come floating to the surface any day now.

It was admittedly a long shot. “Really,” said Washburn, “we were just so weary of this case that we’d hoped for a little time to cut up out on the water.”

Fifteen minutes after they put their boat in on the New Hampshire side of the river, Graham spotted what he thought was a muskrat house. “Isn’t that funny,” he said. No muskrat built a house that far out in the river. They swung the boat over that way.Gibson’s body was floating facedown, seven miles downstream from the iron bridge in Newbury. Several things were remarkable about the body, which was blackened but otherwise in pretty good condition. Dressed exactly as he had been the morning he left his kitchen back in December, Orville Gibson was trussed up like a Christmas goose. The wrists had been tightly bound beneath the thighs, and then cinched to the dead man’s legs. His legs were also tightly bound. While Washburn stayed with the body, Graham went to summon his boss, Lt. Chester Nash.

Within minutes, it seemed to both troopers, word spread that the body of Gibson had been found. At her house on the town common in Newbury, Polly Washburn, who acted as secretary for the state police outpost, received a telephone call from Rorida. “It was a newspaper,” she said, “wanting to know what was happening now that the body of Orville Gibson had been found.” It mystified her how someone in Rorida learned of the discovery so fast. Almost before the corpse was out of the water, reporters from everywhere were heading toward Newbury.

A sensational story was emerging, and soon the whole world would know about it: the story of how the meanest man in one of the prettiest towns in New England had finally got what was coming to him. The story would be told for decades. And it was a complete and communal lie.

The murder gained worldwide attention. It was called Vermont’s vigilante murder, a Yankee lynching. Officially the case has never been solved. A hefty reward still stands for clues leading to its resolution. But nothing—no new witnesses, no new information—has come forth in more than a decade.

Two local men, Ozzie Welch and Frank Carpenter, were eventually charged with the murder of Orville Gibson. They were acquitted in separate trials. Troopers Graham and Washburn and a small army of investigators for the state of Vermont kept digging, hoping that someone would either slip up or finally break under the burden of guilt.But that never happened, and each new investigation seemed to quickly run out of steam. Leads led nowhere. One by one the principals of the drama died or moved away. The truth died or went with them.

Thirty years later Newbury’s population has grown by only about 200, but many of the people who live in the village now are newcomers. “Hearing about Orville Gibson,” says a woman who has lived in the town only a few years, “is like listening to a winter ghost story.”

Bill Graham now lives downstate in Putney where, after a long career in the state police, he’s sheriff of Windham County. His old partner Larry Washburn lives in Putney, too. After 28 years in the state police, he retired to work in a bank, operate a hot-dog cart, and drive a limousine. He enjoyed police work, he says, but cases like that of Orville Gibson haunt a lawman. He would still like the mystery solved. “We poured our guts into that case,” he says with unmistakable emotion, “and came so close to solving it. But all that work really came to nothing.”

There are, he points out, people in Newbury who still might have information that could solve the case. “They still gossip,” he says, “but they quit talking seriously about it years ago.”

* * *

Perhaps the best place to begin to understand why Newbury still clings to its secret is not in the headlines of 30 years ago, where the drama first publicly unfolded, but in the memory of one Leith Henderson who, as a third-grader on a winter’s day in 1920, gazes out of a frosted window of the town schoolhouse.

He sees a large wagon on runners pulled by a yoke of oxen. There are horses and cows. A family is moving into town. The father is a big man with a long, gray beard. There are five children, four girls and one boy. The boy’s name is Orville Gibson.

The Gibson family settles into an old dairy farm on the High Road. They are good Christian people: clean living, no nonsense. Over the next few years the Gibson children work on their father’s farm and get along better than average in school. By the time Orville reaches high-school graduation, in fact, he earns the best marks in his class. As valedictorian, he gives a speech on respect for the law. Some of his classmates resent his personality and work habits. Ordie does not drink or smoke or swear. He will not become “one of the boys,” as they say. They think he is a bit uppity.

A few years later the Great Depression is underway, and money is scarce. But hard work has paid off for Orville Gibson. He has married his high-school sweetheart, schoolteacher Evalyn Runnels, and become a successful traveling salesman for a wholesale grocery firm. Gibson’s dream is still to be a dairyman, and within a few years, thanks to his tireless labor, that goal is attained.

One morning in 1949 Gibson arises at dawn and goes over to the Orange County courthouse in Chelsea. When the doors open, he uses his life’s savings to make a bid on a 300-acre farm just south of Newbury—the old Greer place, once one of the most outstanding dairy farms in all Vermont, but now under foreclosure.

Others in Newbury, including some of its most prominent names, also have their sights set on the Greer place. But they rise too late. When they arrive at the courthouse, the farm has been sold to Orville Gibson. One wealthy citizen in particular, Walter Renfrew, a former Newbury selectman and state senator, is outraged. There are many who hope that Gibson goes bust. But this is far from the case. By 1957 the Gibson Farm is a successful dairy operation.

By the people who know him best, Gibson is greatly admired. John George, the bachelor farmer who lives three houses up the road from the Gibsons, has come to count on Ordie whenever he needs a hand getting in his corn or moving hay. In winter the two men cut wood together. Gibson is quiet and thorough. “Rock steady. The kind of man you can count on in the woods,” John George will say, if asked.

Others can speak of Gibson’s neighborly attentions—how he once cared for the flower beds of an elderly woman who was unable to do so; how he cultivated a meadow of corn for a neighbor who was hospitalized; how he built tables for the church supper; how he delivered the wife of his hired man to the hospital over treacherous icy roads. Like George Henderson, who works on Gibson’s truck at the Texaco station from time to time, many in town have a picture of a retiring but generous man, a proud Vermonter who is always willing to help out when help is needed.

In fact, just a few days before Christmas, Gibson has given his hired man, Eri Martin, a $25 bonus. Martin is a small, skinny man of 56 whose wife and four children occupy a tenant house on the Gibson farm. He has worked for Gibson for almost five years with no complaints.

But on this fateful evening, according to the statement Gibson gave Larry Washburn on reception of the breach-of-peace summons, Gibson advises his hired man to go home and sleep off a drinking binge. Martin refuses. Instead, he picks up a heavy wheelbarrow containing two 40-quart cans of milk and rolls it down the milk-house ramp. His thin legs buckle. The wheelbarrow’s handles crack Martin in the ribs, and the milk gurgles into the dirt. Gibson angrily orders his hired man home and says they will settle up later.

Martin follows his boss back into the barn, enraged that he will be docked for the spilt milk. Gibson tells him to get out. “No son of a bitch is going to put me out of the barn,” Martin boasts. Gibson responds by throwing his hired man out of the barn.

Martin hobbles home and claims to his son that Gibson beat him up, cracked his ribs, and injured his kidneys. He will later tell state police that the injuries occurred when he “fell down.”

During the next week, the week between Christmas and New Year’s, there are holiday parties going on everywhere in Newbury, and the story of Eri Martin’s ordeal, as one man recalls it, “becomes the hot topic.” At one point Walter Renfrew remarks that Orville Gibson “should be tarred and feathered and rode out of town on a rail.”

Evalyn Gibson receives a threatening phone call from a well-known man in town. “Tell your husband we heard about the Christmas party he gave Eri Martin,” he says. “If he comes down to the village, we might be able to arrange a New Year’s party for him.” Over that one short week she receives six anonymous postcards promising dire retribution.

On the night of December 30, she notices a large number of parked cars and several visitors over at the Martin house. That night there are two other parties going on in Newbury, but the Gibsons are not invited to any of the festivities. They have work to do; they retire at 8:30p.m.

Seven hours later, Orville Gibson rises, gets dressed, and makes his last trip to the milking barn.

* * *

Through scant physical evidence— the rope used to truss up Gibson, and the critical eyewitness account of a local doctor named John Perry Hooker—the state of Vermont was able to link the alleged kidnapping and murder of Gibson to two local men, one Robert Orzo “Ozzie” Welch, the high-school janitor; and Frank Carpenter, a man who was known to local police for his penchant for drinking and fist-fighting.

Dr. Perry told police that he’d been driving past the Gibson place early on the morning of December 31 and had seen a two-toned Kaiser sedan parked on the side of the road about a hundred yards from the Gibson barn. There were several men in and around the car, he testified, and Dr. Perry recognized one of them as Ozzie Welch, who happened to be one of his patients. The sedan was later traced to West Newbury and Frank Carpenter.

When the police presented Welch with the rope used to tie up Gibson, according to one account, he exclaimed, “By God, boys, that’s my rope!” He would give no less than five different versions of where he was on the morning of the Gibson disappearance and staunchly maintained his innocence throughout.

In an effort to learn more about the identities of the other men Dr. Hooker claimed to have seen on the road that morning, Vermont authorities began to invite various citizens of Newbury to submit to lie-detector tests. In those days the state of Vermont did not own a polygraph machine, but the state of New Hampshire did. About 50 people in town were offered a free police escort to Concord.

“Suddenly,” says George Henderson, who was one of many who were “invited” to take the test, “the people of Newbury had nothing to say about the murder.” Several of the town’s leading names were given as many as four or five polygraph tests. The day before he submitted to his only polygraph test, it was reported, Ozzie Welch appeared at Dr. Hooker’s door to refill a prescription for tranquilizers. Technicians, it was later revealed, had difficulty keeping him awake during his test.

When the state of New Hampshire’s polygraph machine gave out from constant use, Vermont bought its own. During the subsequent years of the investigation about 80 individual polygraph tests would be administered to the citizens of Newbury, yielding some interesting facts about the habits of Newbury but no clues as to who killed Orville Gibson.

“The polygraph did turn up some rather odd stuff,” recalls Graham. “We found out that several things were thrown off the Newbury bridge—at least three ponies, and several calves, plus parts of several old cars. But no body. We cleaned up a couple of deer jacking cases through the polygraph, but never found out who killed Gibson.” The arraignment of Welch, and shortly thereafter Carpenter, in early November 1958 divided Orange County and the town of Newbury. There were those, mostly from town center, who had known Welch and Carpenter their whole lives and supported them in their ardent denials. And then there were others, generally from outside the village, who were convinced that Welch and Carpenter were simply two henchmen in a small circle of locals who had always resented Orville Gibson and used the occasion of the bruised hired man to try to bring Gibson down a notch.

Ozzie Welch’s trial took place inside the Orange County Courthouse in Chelsea almost one year later. The state’s case centered on the testimony of Dr. Hooker and the rope used to truss up Orville Gibson. In an effort to link Welch or anyone else to the rope, Graham and Washburn and other investigators had gone to exhaustive lengths. The rope was an odd make. It had rusty nail holes in it, suggesting it had come from a barn somewhere. They managed to trace the rope to its manufacturer in Plymouth, Massachusetts. They checked every barn within a wide radius of Newbury to try to establish a link. They got nowhere. But along the way, a revealing experiment was tried. Graham explained, “At the motel where we had interviewed suspects, Washburn and I took a rope and tied up Lieutenant Nash in the same way Gibson had been tied up. Nash was a big man, too. When we finished, he was complaining that he could barely breathe. We had to cut him loose. If we’d left him long, he would have suffocated.”

That development, though in no way useful to the prosecution of Welch, nevertheless helped crystallize a theory about the possible motive. Said Graham: “We were pretty sure a certain group of fellas had been together drinking that night. It was easy enough to picture what happened. They jumped him and tied him up. Later there were rumors that they meant to leave him on the town common for one of us to find. This is a small town. These men weren’t professional killers. But they didn’t know Gibson had a respiratory problem. When they bound him up, he suffocated. When they saw that he was dead, they panicked and dumped him in the river. Then they made a deal to keep it quiet. It was a mean prank that ran away from them.”

The prosecution presented 28 witnesses. The defense put no one on the stand, but asked the judge for a directed verdict of not guilty. The judge so ruled—a rare occurrence in a capital case. Ozzie Welch went free, to the delight of many in Newbury. “I never thought I was guilty,” Welch was quoted as saying. But a town’s unhappy legacy was also being written at that very moment.

A story on the proceedings appeared in the Sunday Express of Glasgow, Scotland, under the headline: “Meanest Man Lynched and Town Shields Fifteen Killers.” In Jackson, Mississippi, the Daily News editorialized: “Up in Vermont, 47-year-old dairy farmer Orville Gibson was lynched by a vigilante gang. This happened two years ago but those fast moving, swift-thinking, finger-pointing, Pulitzer Prize-winning Yankee editors hid the body all the time. They were too busy writing about Southern injustice.”

There were similar inflammatory newspaper stories and editorial columns as far away as London and Moscow, as well as plenty of press closer to home.

In December, two months after his acquittal, Ozzie Welch entered Cottage Hospital in Woodsville, New Hampshire, and died of cancer. “He died,” states an elderly Newbury man who was also asked to account for his whereabouts on the night Gibson went missing, “because they questioned him too long. Guilt or worry or something ate his insides up.”

Frank Carpenter’s murder trial began in Chelsea in April 1960. This time the state’s case was weakened by unexpected developments: several key witnesses, including Dr. Hooker, were extremely vague in their recollections. Witnesses recanted their written statements.

Carpenter was also declared not guilty. That appeared to be the end of it. Periodically in the years that followed, there were calls to reopen the Gibson case. Anonymous letters containing new leads and accusations drifted into the state attorney general’s office, but in almost every case they proved useless. Evalyn Gibson sold the farm and moved downriver to Orford, New Hampshire, where she remarried and lived quietly until her death in 1973. Frank Carpenter died in 1972.

Troopers Graham and Washburn got on with their duties, moved on up in their careers. As a direct result of the complex investigation of the Gibson murder, the state of Vermont formed a Bureau of Criminal Investigations to handle any future “untimely deaths” that become something more.

* * *

And now it is difficult to even find anyone in Newbury who will discuss the Gibson murder, its Ghost of Christmas Past. Barbara Welch, the town clerk, is related to Ozzie Welch (she married his nephew Barney) but she does not wish to talk about the killing or its aftermath. She says everyone wants to forget it, period. She is coolly polite but otherwise reluctant to speak to the occasional reporter who still comes calling.

If you press hard enough, you can still hear stories, rumors, speculations—everything off-the-record. One woman lets on that as many as 50 people in town knew the identities of Orville Gibson’s murderers. “Think about it,” she says, “You had nine or ten men at a drinking party, and those men all had families. What’s amazing to me,” she maintains, “is that all those people could have been so quiet so long. It’s either a compliment to the Vermont character or a sad commentary.”

Bill Graham still keeps a hunting cabin in Newport, not far from Newbury, and visits his camp there several times a year. “ I am still known thereabouts,” he explains, “and every year I can’t resist the fantasy that some old fella will come up to me and say, ‘All right. I’ll tell you what really happened. I want to get this off my conscience.’ “

But it hasn’t happened. He knows that someone in beautiful Newbury may still know who killed Orville Gibson. And someone is still not talking.