Magazine

Old Leather Man | A Connecticut Legend

A local legend like that of the Old Leather Man — Connecticut’s most famous tramp — can easily die of neglect unless someone takes an abiding interest in keeping it alive. The Old Leather Man was a legendary beggar who trudged a wide circle through southeastern Connecticut and western New York State during the late […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan A local legend like that of the Old Leather Man — Connecticut’s most famous tramp — can easily die of neglect unless someone takes an abiding interest in keeping it alive.

The Old Leather Man was a legendary beggar who trudged a wide circle through southeastern Connecticut and western New York State during the late 19th century. His legend and the mysteries of his life came to mean a lifetime’s search for Roy Foote, who otherwise spent his life as a banker. In his house, which he and his wife Sarah built on the south comer of his father’s farm, Roy Foote had accumulated closets full of information and stacks of photographs. He also had a large collection of memorabilia such as a tin pipe and a hatchet that belonged to the Leather Man. Roy even devised a suit of clothes believed to be a close replica of the Leather Man’s cumbersome and peculiar leather pants, leather jacket, leather shoes, and leather hat.

The Leather Man never spoke for himself, for the most part leaving his riddle to Roy Foote to puzzle and piece together, the way he did the Leather Man’s suit, a crazy quilt of leather scraps boldly stitched together with leather thongs. On Halloween Roy used to put on the Leather Man’s suit, his shoes, and his roomy hat, which fit like an upside-down pot, and shoulder his great big leather bag. Leaning on the walking stick he made to look just like the Leather Man’s, he’d open the door to greet surprised trick-or-treaters.

In southern sections of Connecticut, the story of the Leather Man was an oft-told one. It has been written up as books, and it’s been included in countless anthologies of New England lore. “Hundreds of people have written the Old Leather Man’s story,” Sarah Foote told me, “and not just in books and magazines. The students at the school, generations of them, used to come here and talk to Roy, and then they’d go back and write up their term papers about the Old Leather Man. In that sense it’s a story that we all share. And of course, Roy has written about him countless times. When people want to know about the Old Leather Man, they always call up Roy.”

His story was even made into a film that was shown by Connecticut Public Television. Ed McKeon, who wrote and produced the film, said that when he first started work on it, he had only a small file. In his research he kept coming across Roy’s name. And often the source of other people’s stories was Roy Foote. “I’d be interviewing someone and it would all sound like firsthand information. Then I’d say, ‘Gee, how do you know all this?’ and the person would say, ‘Oh, Roy Foote used to come to our town and talk about the Leather Man.’ ”

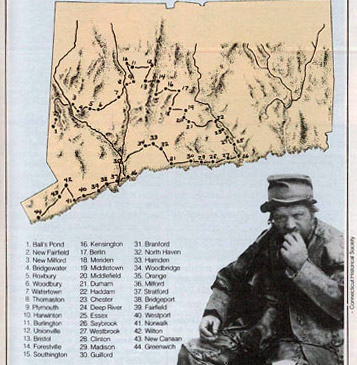

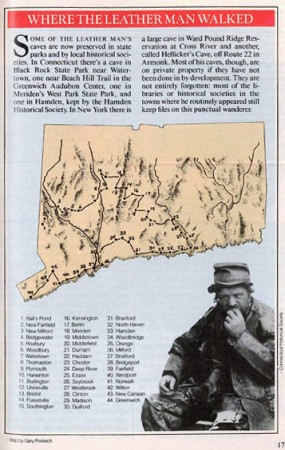

It was in the early forties that Roy and Sarah first heard about the Leather Man. Lifelong nature lovers, Sarah and Roy spent a lot of their weekends cave-crawling — spelunking as it came to be called. On one such excursion, Roy and Sarah and another of the group stopped under a ledge, and their companion told them the story of this mysterious, silent tramp who slept in caves and walked on an unwavering course through more than 40 towns from Essex to Greenwich to Ossining, New York, to New Fairfield to Middletown and so on, the endless circle.

The loop was said to have been 365 miles, and it took the Leather Man exactly 34 days to make a complete circuit. Punctual as a banker, he’d show up at the same place 34 days later, mutely asking for something to eat. No one knew who he was; he never spoke a word. He was a survivor who had lived through 32 New England winters, living in shallow caves, not much more than rock overhangs, until his face froze during the Blizzard of ’88, causing a cancer that eventually killed him. (This storm, which killed hundreds and turned New England upside down for weeks, delayed the Leather Man only four days.) He was but a tramp among thousands during that rough, scrappy period in New England’s history, yet a tramp so endearing that special legislation was passed to exempt him from stern new laws that called for bizarre and cruel methods of eliminating beggars from the landscape. He was a man who had no known roots, no name, no reason for his peculiar and almost eerie trek, and yet a man of apparent principles. He never took money; he never accepted clothes or charity of any kind except food. If he was ridiculed or jeered at, he never returned to that place; and in spite of his forbidding appearance in his voluminous outfit, he brought harm to no one.

To find out more, Roy began by asking the people who owned the land around the Leather Man’s caves what they knew about him. They told him they’d mark the Leather Man’s arrival on their calendars and sometimes bake something special that day. Roy found that people often had a picture of the Leather Man in their family album and that sometimes teachers would let classes out early if it was the time when the Leather Man, who was gentle with children, was due to arrive. One interview led to another or sometimes two more. Roy found that each person who had known the Leather Man had his own story and that it differed from anyone else’s. “When I was growing up in the forties and fifties, we spent nearly every weekend going out on interviews,” Roy’s daughter Lynn Boyle recalled. “Dad would spend hours sometimes talking to people who had fed the Old Leather Man or whose mothers had fed the Old Leather Man along his route.”

With so many stops along such a long route, there were hundreds who knew the Leather Man, and as Roy Foote gradually began to discern, there was also more than one Leather Man — there were three. At least, there were three identities presumed to be his: Jules Bourglay, Randolph Mossey, Zacharias Boveliat. Roy kept separate file drawers for the three identities and continued his research, more intrigued than ever. Knowing that, he began to feel that there were two different men, one of them an imposter. “Roy knew by the way people talked which one they were talking about. Randolph Mossey dressed like the Old Leather Man and followed roughly the same route, but he came along after the Old Leather Man died,” Sarah Foote explained. “He didn’t come round as often and he spoke. He even did odd jobs. Except for the clothes, he wasn’t really anything like the Old Leather Man. We think that he was simply trying to cash in on a good thing.” The other two stories were up for grabs, one as convincing and well substantiated as the other.

Roy and Sarah Foote chose, without doubt, the story of Jules Bourglay.

No one seems to know where this legend came from, but the popular version goes, briefly, like this: Jules Bourglay, a young man from Lyons, France, fell in love with the daughter of a wealthy leather merchant who didn’t think young Jules was good enough for his daughter. However, he was willing to give him a chance. As a trial, he hired Jules to work in his leather company, with the stipulation that if he did well, he could marry his daughter. Jules took on the challenge. Anxious to prove his worth, he took investment risks that backfired and swept his lover’s father’s fortune down the drain. Distraught, some say crazed, he entered an institution and then, after some time, vanished. Shortly afterward, it is said, he resurfaced in Connecticut and began his penitent, clockwise trudge across the fields and valleys, his long 30-year dirge to his lost love.

Though the source of the story is unknown and though they twice wrote to Lyons, France, inquiring if there ever was such a person as Jules Bourglay and both times they were told there was not, Sarah and Roy Foote never lost faith in it. Ed McKeon included the version of Jules Bourglay in his film. Yet, having spent a year researching these and other versions, and having relied heavily on Roy Foote’s information, he said he didn’t believe that version for a minute. “There are so few facts. I don’t know that any of the versions could be proven. The one I prefer is that he was the son of a wealthy man and fell in love with a poor girl who was murdered. That would better fulfill the idea of penance. It makes more sense.”

But legends survive not because they happened but because of the telling. Most people prefer the story of Jules Bourglay, perhaps because it is true or because they want to believe it is true or because Roy Foote popularized that version. It is the story he took out on the road with him as he and Sarah gave countless lectures and story hours on the Old Leather Man. It was an hour-long presentation which he enhanced with slides he had taken along the Leather Man’s route. There were pictures of the many caves where the Leather Man slept and pictures of some of the places he was known to have stopped, plus reproductions of pictures of the Leather Man (of which there were more than might have been expected — merchants offered them as sales gimmicks to gullible customers). Though Roy had told the story thousands of times, each time he gave the talk he told it as if it were the first time, his eyes animated, his voice full of tension. At the end he’d surprise the audience by having someone dress up in his Leather Man’s suit and shuffle down the aisle to the front of the room. Some people came again and again to his rural kind of vaudeville show.

The Leather Man was found dead in one of the caves in 1889. He was buried in a pauper’s grave not far from where he was found in Ossining, New York. His grave was marked with an iron pipe. Roy Foote and others who called themselves Friends of the Leather Man joined together to have a grave marker engraved and installed. In 1953 the Leather Man received a head-stone which seemed to decide once and for all who he was. On the back side of a stone that had been carved for someone else and then discarded, is the epitaph: The Final Resting Place off Jules Bourglay/ of Lyons, France/”The Leather Man”/who regularly walked a 365/mile route through Westchester/ and Connecticut from the Connecticut/River to the Hudson/living in caves in the years 1858-1889.

The legend of the Old Leather Man was an odd patchwork of truth and fantasy, and perhaps because of Roy Foote’s tireless telling of the tale, the story may never die. “Because, you see, it’s not like any other legend,” Sarah Foote explained. ” It’s not like Rip Van Winkle because this one is true. This one happened. Right here in our own backyard.”

Excerpt from “The Leatherman’s Keeper,” Yankee Magazine, February 1985.

A local legend like that of the Old Leather Man — Connecticut’s most famous tramp — can easily die of neglect unless someone takes an abiding interest in keeping it alive.

The Old Leather Man was a legendary beggar who trudged a wide circle through southeastern Connecticut and western New York State during the late 19th century. His legend and the mysteries of his life came to mean a lifetime’s search for Roy Foote, who otherwise spent his life as a banker. In his house, which he and his wife Sarah built on the south comer of his father’s farm, Roy Foote had accumulated closets full of information and stacks of photographs. He also had a large collection of memorabilia such as a tin pipe and a hatchet that belonged to the Leather Man. Roy even devised a suit of clothes believed to be a close replica of the Leather Man’s cumbersome and peculiar leather pants, leather jacket, leather shoes, and leather hat.

The Leather Man never spoke for himself, for the most part leaving his riddle to Roy Foote to puzzle and piece together, the way he did the Leather Man’s suit, a crazy quilt of leather scraps boldly stitched together with leather thongs. On Halloween Roy used to put on the Leather Man’s suit, his shoes, and his roomy hat, which fit like an upside-down pot, and shoulder his great big leather bag. Leaning on the walking stick he made to look just like the Leather Man’s, he’d open the door to greet surprised trick-or-treaters.

In southern sections of Connecticut, the story of the Leather Man was an oft-told one. It has been written up as books, and it’s been included in countless anthologies of New England lore. “Hundreds of people have written the Old Leather Man’s story,” Sarah Foote told me, “and not just in books and magazines. The students at the school, generations of them, used to come here and talk to Roy, and then they’d go back and write up their term papers about the Old Leather Man. In that sense it’s a story that we all share. And of course, Roy has written about him countless times. When people want to know about the Old Leather Man, they always call up Roy.”

His story was even made into a film that was shown by Connecticut Public Television. Ed McKeon, who wrote and produced the film, said that when he first started work on it, he had only a small file. In his research he kept coming across Roy’s name. And often the source of other people’s stories was Roy Foote. “I’d be interviewing someone and it would all sound like firsthand information. Then I’d say, ‘Gee, how do you know all this?’ and the person would say, ‘Oh, Roy Foote used to come to our town and talk about the Leather Man.’ ”

It was in the early forties that Roy and Sarah first heard about the Leather Man. Lifelong nature lovers, Sarah and Roy spent a lot of their weekends cave-crawling — spelunking as it came to be called. On one such excursion, Roy and Sarah and another of the group stopped under a ledge, and their companion told them the story of this mysterious, silent tramp who slept in caves and walked on an unwavering course through more than 40 towns from Essex to Greenwich to Ossining, New York, to New Fairfield to Middletown and so on, the endless circle.

The loop was said to have been 365 miles, and it took the Leather Man exactly 34 days to make a complete circuit. Punctual as a banker, he’d show up at the same place 34 days later, mutely asking for something to eat. No one knew who he was; he never spoke a word. He was a survivor who had lived through 32 New England winters, living in shallow caves, not much more than rock overhangs, until his face froze during the Blizzard of ’88, causing a cancer that eventually killed him. (This storm, which killed hundreds and turned New England upside down for weeks, delayed the Leather Man only four days.) He was but a tramp among thousands during that rough, scrappy period in New England’s history, yet a tramp so endearing that special legislation was passed to exempt him from stern new laws that called for bizarre and cruel methods of eliminating beggars from the landscape. He was a man who had no known roots, no name, no reason for his peculiar and almost eerie trek, and yet a man of apparent principles. He never took money; he never accepted clothes or charity of any kind except food. If he was ridiculed or jeered at, he never returned to that place; and in spite of his forbidding appearance in his voluminous outfit, he brought harm to no one.

To find out more, Roy began by asking the people who owned the land around the Leather Man’s caves what they knew about him. They told him they’d mark the Leather Man’s arrival on their calendars and sometimes bake something special that day. Roy found that people often had a picture of the Leather Man in their family album and that sometimes teachers would let classes out early if it was the time when the Leather Man, who was gentle with children, was due to arrive. One interview led to another or sometimes two more. Roy found that each person who had known the Leather Man had his own story and that it differed from anyone else’s. “When I was growing up in the forties and fifties, we spent nearly every weekend going out on interviews,” Roy’s daughter Lynn Boyle recalled. “Dad would spend hours sometimes talking to people who had fed the Old Leather Man or whose mothers had fed the Old Leather Man along his route.”

With so many stops along such a long route, there were hundreds who knew the Leather Man, and as Roy Foote gradually began to discern, there was also more than one Leather Man — there were three. At least, there were three identities presumed to be his: Jules Bourglay, Randolph Mossey, Zacharias Boveliat. Roy kept separate file drawers for the three identities and continued his research, more intrigued than ever. Knowing that, he began to feel that there were two different men, one of them an imposter. “Roy knew by the way people talked which one they were talking about. Randolph Mossey dressed like the Old Leather Man and followed roughly the same route, but he came along after the Old Leather Man died,” Sarah Foote explained. “He didn’t come round as often and he spoke. He even did odd jobs. Except for the clothes, he wasn’t really anything like the Old Leather Man. We think that he was simply trying to cash in on a good thing.” The other two stories were up for grabs, one as convincing and well substantiated as the other.

Roy and Sarah Foote chose, without doubt, the story of Jules Bourglay.

No one seems to know where this legend came from, but the popular version goes, briefly, like this: Jules Bourglay, a young man from Lyons, France, fell in love with the daughter of a wealthy leather merchant who didn’t think young Jules was good enough for his daughter. However, he was willing to give him a chance. As a trial, he hired Jules to work in his leather company, with the stipulation that if he did well, he could marry his daughter. Jules took on the challenge. Anxious to prove his worth, he took investment risks that backfired and swept his lover’s father’s fortune down the drain. Distraught, some say crazed, he entered an institution and then, after some time, vanished. Shortly afterward, it is said, he resurfaced in Connecticut and began his penitent, clockwise trudge across the fields and valleys, his long 30-year dirge to his lost love.

Though the source of the story is unknown and though they twice wrote to Lyons, France, inquiring if there ever was such a person as Jules Bourglay and both times they were told there was not, Sarah and Roy Foote never lost faith in it. Ed McKeon included the version of Jules Bourglay in his film. Yet, having spent a year researching these and other versions, and having relied heavily on Roy Foote’s information, he said he didn’t believe that version for a minute. “There are so few facts. I don’t know that any of the versions could be proven. The one I prefer is that he was the son of a wealthy man and fell in love with a poor girl who was murdered. That would better fulfill the idea of penance. It makes more sense.”

But legends survive not because they happened but because of the telling. Most people prefer the story of Jules Bourglay, perhaps because it is true or because they want to believe it is true or because Roy Foote popularized that version. It is the story he took out on the road with him as he and Sarah gave countless lectures and story hours on the Old Leather Man. It was an hour-long presentation which he enhanced with slides he had taken along the Leather Man’s route. There were pictures of the many caves where the Leather Man slept and pictures of some of the places he was known to have stopped, plus reproductions of pictures of the Leather Man (of which there were more than might have been expected — merchants offered them as sales gimmicks to gullible customers). Though Roy had told the story thousands of times, each time he gave the talk he told it as if it were the first time, his eyes animated, his voice full of tension. At the end he’d surprise the audience by having someone dress up in his Leather Man’s suit and shuffle down the aisle to the front of the room. Some people came again and again to his rural kind of vaudeville show.

The Leather Man was found dead in one of the caves in 1889. He was buried in a pauper’s grave not far from where he was found in Ossining, New York. His grave was marked with an iron pipe. Roy Foote and others who called themselves Friends of the Leather Man joined together to have a grave marker engraved and installed. In 1953 the Leather Man received a head-stone which seemed to decide once and for all who he was. On the back side of a stone that had been carved for someone else and then discarded, is the epitaph: The Final Resting Place off Jules Bourglay/ of Lyons, France/”The Leather Man”/who regularly walked a 365/mile route through Westchester/ and Connecticut from the Connecticut/River to the Hudson/living in caves in the years 1858-1889.

The legend of the Old Leather Man was an odd patchwork of truth and fantasy, and perhaps because of Roy Foote’s tireless telling of the tale, the story may never die. “Because, you see, it’s not like any other legend,” Sarah Foote explained. ” It’s not like Rip Van Winkle because this one is true. This one happened. Right here in our own backyard.”

Excerpt from “The Leatherman’s Keeper,” Yankee Magazine, February 1985.

Great article. It was a great story about a man who definitely had some reason for walking!

My mother still has on old picture of him. She grew up in the South Salem, NY/Ridgefield, CT area where he was known to many.

One of his undiscovered caves, I found out from my mom, one we played in . Is in ridgefield ct. Limestone rd.