The Day Kurt Newton Disappeared | Yankee Classic

The Newton family was camping at Coburn Gorge in northern Maine over Labor Day weekend in 1975 when Kurt, age 4, disappeared. What followed has been termed “the most extensive woods search in the history of Maine.” But all the thousands of volunteer searchers ever found were unanswered questions.

The Day Kurt Newton Disappeared | Yankee Magazine, September, 1979

Excerpt from “’The Day Kurt Newton Disappeared,” Yankee Magazine, September 1979.

Even now, four years later, Ron and Jill Newton will sometimes let their minds drift back and silently relive that Labor Day weekend, hour by hour, trying to snatch it all back and hold it still at 10:00 A.M. Sunday, August 31, 1975.

It had been a grand weekend, camping with their children, Kimberly, age six, and Kurt, age four, and three other families from their home in Manchester, Maine. Natanis Point Campground was small and remote, its fifty-eight sites cut from a paper-company forest 1,300 feet above sea level in Chain of Ponds, a wilderness township six miles below the Canadian border at Coburn Gore. Campers fished from two ponds that were deep and cold. When a fisherman landed a salmon from the small wooden bridge below the thread of beach, he would yelp with pleasure and a crowd would gather. Mountains loomed over the ponds, and when at night a loon wailed and the forest pressed close on all sides, you knew you were away.

That Friday the Newtons arrived first. It was their first trip with the recently acquired secondhand tent trailer, what Jill called “our luxury.” They gathered wood along an abandoned logging road nearly a mile from their campsite. “It isn’t camping without a bonfire,” Kurt said happily. On Saturday their friends arrived, and Kimberly raced her bicycle through mud puddles while Kurt furiously pedaled his big-wheel tricycle after her, trying to keep up. It was the end of summer, and there were huge meals and laughter and quiet, chilly nights by a roaring fire. To Jill Newton things felt “just right,” which was not unusual.

“We’d been married eight years,” she would say later, “and everything just seemed to work right. We got along so well. We had saved for four years to buy a house, and when we were ready, there was our house across the street from the elementary school. From before we were married we always said we’d have two children and no more. We had a girl and then by a stroke of luck we had a boy, just what we wanted. It became a sort of joke between Ron and me. We’d say, ‘How did we get so lucky? “

Sunday broke with a heavy mist over the ponds. Ron took the bite off the morning, using the last of the wood to light a fire. Kurt slept until nine, fighting off a cold; when he awoke he shivered. “I’m so glad Daddy built a bonfire,” he said. Ron dressed Kurt for the damp, chilly morning: red jersey, navy blue sweatshirt, speckled red and black corduroys. Kurt tugged on dark brown shoes over mismatched white socks and topped off his outfit with a favorite navy blue jacket decorated with baseball emblems.

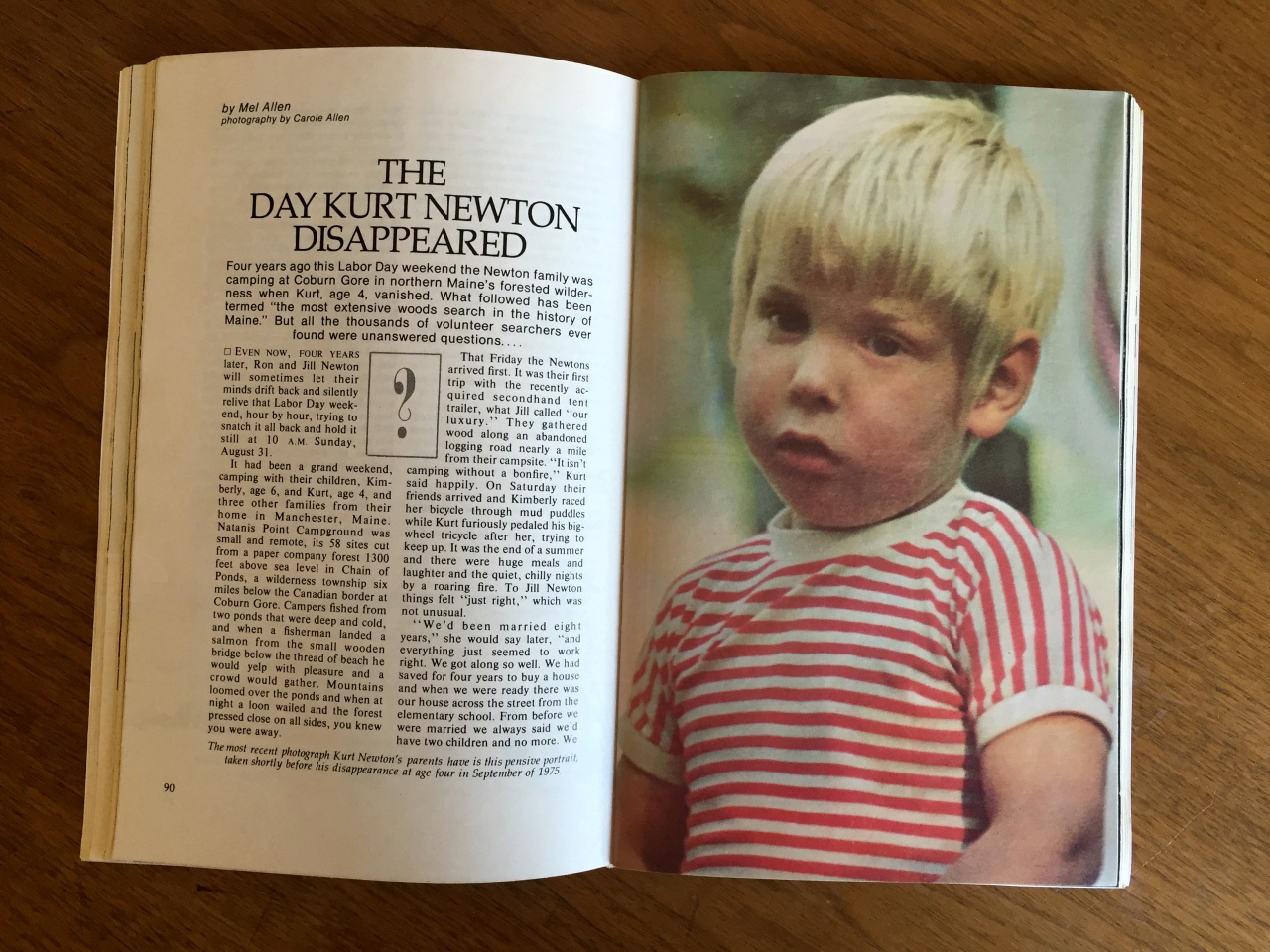

Jill called Kurt “a head-turner,” a striking child with an impish sweet face, bright blue eyes, and platinum blond hair. “The loveliest, sweetest towhead kid you ever saw,” said a neighbor. Though he was rugged, Jill I worried that Kurt was “tied to my apron strings.” He was painfully shy and afraid of being alone, even for a few moments. “Sometimes when grocery shopping, I’d walk around the corner and he’d stand there, and I’d come back and find him almost in tears,” Jill said. “I could put him outside to play all day and he would never leave. He always made sure I knew where he was.”

Kimberly would often spring into the shallow woods behind their house and implore her brother to join her climbing the trees or playing hide-and-seek. As Kurt quivered on the edge of the lawn, she would tease, “Kurt’s such a baby.” Once Jill asked him why he wouldn’t go with Kimberly into the woods. “Momma, there’s monsters in there,” he answered.

After a hearty camper’s breakfast — fried potatoes, ham and eggs, toast, and juice — Kurt put a doughnut on a stick and warmed it over the flames, then threw the paper plates into the fire. Jill gathered the mud-soaked sneakers from the day before and with her friends walked to the bathhouse fifty yards away to wash them. Kim began playing a game and assumed Kurt would ride his tricycle around the campsite. Ron climbed into his Bronco, ax in hand, and drove off to get firewood. This is where their minds halt, confused and troubled, where Ron and Jill Newton try to snatch it all back. For then a friend from her trailer heard a plaintive “Daddy, Daddy,” as Kurt apparently ran to his tricycle, a determined little boy trying to catch his father, and pedaled away — into a mystery as deep as the forest that seemed to swallow him without a trace.

From the campground, a rut-strewn logging road runs north, parting the forest, which gives way reluctantly. An abandoned horse hovel sits back from the road, nearly obscured by undergrowth, about a quarter-mile from the Newtons’ campsite. Here, twelve-year-old Lou Ellen Hanson, returning from a walk, was startled to see the small boy churning past on his tricycle. “Hey,” she called out, “do your parents know where you are?’ but the boy made no reply as he pedaled on, and she turned toward the campground.

The road continues another quarter-mile, then forks. To the left it leads to a small campground dump on a knoll, past a shaky bridge over a stream. To the right it continues for a mile, then gives way to heavy undergrowth. For the next several miles leading to Route 27 the road is nearly impassable to all but four-wheel-drive vehicles. The road and its “back-door” access to his campground was a source of irritation to campground owner Lloyd Davidson. Fishermen would use it to fish his waters, or to use his showers. He would grumble that if it were his land and not leased from the paper company, he would have bulldozed it long ago. It was on this road, about a half-mile past the fork, where Ron Newton went to chop wood, the sounds of his ax barely audible from the dump.

Jack Hanson, Lou Ellen’s father, who served as a volunteer caretaker for the campground, found the tricycle just before the steep rise leading to the dump. It was off the road, at the edge of the woods, a position that reminded a state police investigator “of a little boy who’s been told never to leave his things on the road.” Thinking it had been discarded, Hanson carried it over the rise and heaved it atop the trash heap, then drove back to the campground.

“We hung the sneakers on the line,” Jill Newton recalls. “We’d been gone at the most ten minutes. We saw no Kurt and no tricycle, so we started walking around asking campers if they’d seen a blond boy on a big-wheel tricycle. I began to think he must have gone with the men to get firewood, but then they rounded the comer and no Kurt. We met Jack, and he told us he had found the trike at the dump. We raced to the dump, and there was Kurt’s big-wheeler, but no one in sight, not a sound to be heard.

“‘My God, someone’s taken him!’ were my first words.” The men quickly reassured her that Kurt must have thought his father was just a little ways into the woods and had wandered in after him. They would find him in no time. “How could a boy who won’t even go into the woods with his sister around his own home go into these incredibly wild woods?’ she asked. But it would be only the first of many baffling questions with no answers.

Duane Lewis, Maine Fish and Game warden inspector, was patrolling near his home in Phillips, about seventy-five miles south of Chain of Ponds, when the call came from the regional game warden that a child was lost. A small search party had already been organized from campers to comb the logging roads. Lewis, at thirty-nine, was a veteran warden with fourteen years and nearly seventy-five searches under his belt. No search of which Lewis had been in charge had failed to find a person missing in the woods. Because the missing boy was only four and the temperature was expected to drop into the 20’s that night, Lewis called area wardens for assistance even as he sped northward.

A woods search strategy can never be haphazard. Its plotting is an intricate balance between intuition and science. With grownups the contour of the land, or the presence of streams, can be weighed against the age and expected endurance of the victim. But a search for a four-year-old becomes a chess match with a cosmic jester. Usually, the will of a child lost in the woods is fragile, easily broken; he will sit by a tree and cry, and within a few hours searchers will find him. But on rare occasions, a child’s stamina outlasts that of a grown man. Propelled by an inward trembling, he will outstrip his methodical pursuers, and all bets are off. Duane Lewis was convinced that “it’s much harder to plan a search for a small child,” but he was equally convinced when he arrived at the scene at 4:00 P.M. that with the twenty-nine searchers already at hand, the boy would be home by nightfall.

Soon a warden service helicopter and a search plane augmented the ground search concentrating on tote roads near the dump. Kurt had always been fascinated with the National Guard helicopters that whirred over his house, and Jill was certain he would respond to the warden’s calm voice calling him on the loudspeaker from above the trees. “Kurt, I’m up in the helicopter. Your mommy and daddy are waiting for you, and I want you to follow me back to the camp. Walk towards the helicopter. Don’t sit down. Don’t be afraid. Just stand up and walk, and I’ll take you back.” Later, Jill would consider that first day’s efforts and say, “Even if he’d somehow gotten out of the prime area, that helicopter would have brought him back.”

The temperature dropped to 26 degrees. Jill thought, “How frightened Kurt is. How he must wonder, ‘Why doesn’t my mommy come get me? “

Manchester. Maine, heard the news at 7:00 P.M. Ron Newton had grown up beside the firehouse, and neighbors could remember the tall, thin boy racing frantically after the fire truck at the first blast of the whistle, being pulled aboard with his shirttail flying. He had joined the volunteer fire department at seventeen. He was hometown, and had never left, becoming a supervisor for the highway department. Soon streams of cars from Manchester headed north.

Jill had grown up eighteen miles away in the small town of Wayne. She had been the only girl in her one-room schoolhouse, and she lived above her father’s general store. Everybody knew Jill Lovejoy. When word spread that her little boy was lost, the cars from Wayne joined those from Manchester on Route 27. When they poured into the campground late at night, an eerie sight awaited them: Ron and Jill calling into a loudspeaker at the edge of the woods by the dump, “hoping in the still of the night we’d hear his cry.” Wardens probed the darkness, their lantern beams flashing among the trees.

By first light on Labor Day a bloodhound team scented on Kurt’s pajamas. A year earlier the same bloodhounds had been instrumental in tracking a two-year-old girl lost in the New Sharon woods. As the search party, now swelled to nearly two hundred, waited, the hounds bolted from the dump, ran ten yards, then whirled in confusion, apparently overwhelmed by the conflicting scents from Sunday’s heavy search.

The weather steadily worsened, becoming, as one searcher said, “dark, dank, and miserable with the fog settling in and everybody soaking wet and chilled to the bone.” The searchers began to realize the enormity of their task. The woods were filled with holes, “some bigger than a man,” as Duane Lewis said, and piles of rocks and boulders covered with moss, and enormous root cavities. Years of windstorms had taken their toll. Briars scratched at the searchers’ faces as they crawled through the blow-down looking in vain for a small boy’s footprints, or bits of clothing torn as he stumbled past. Holes under boulders were tediously checked, then rechecked by other searchers, each check indicated by a marking slash, until the forest was pocked with their grim graffiti. The search grew into what officials described as “the most intensive woods search in the history of Maine.”

Probably nothing grips the hearts and minds of people as does the specter of a lost child wandering helplessly in a woods, waiting for rescue. Radio and television appeals touched Mainers from all walks of life. Buses brought workers from paper mills and factories from throughout northern and central Maine. College students, crusty woodsmen, and an elite six-man mountain rescue unit joined together at Natanis Pond. Cars lined Route 27 for more than a mile, the feet of bone-weary volunteers poking through half-opened windows. To feed the searchers, who one day numbered fifteen hundred, women from the Kingfield-Stratton area solicited food from their neighbors to stock their civil defense kitchens, until soon donations poured in from as far away as one hundred miles.

The Newtons were determined that nothing would be left to chance. When Jill learned from a searcher that a top-secret plane had been used in Vietnam to find guerrillas in dense jungle, she ran to the wardens. “I don’t care what it costs or how it works,” she said. “I just want it to tell me where my son is.” And late Monday night the $10-million C-130H gunship lifted off from Eglin Air Force Base in Pensacola, Florida, with her nine-man crew, the first time it would be used in a civilian search. The plane was equipped with infrared sensors and low-light television-sensor equipment for nighttime use, equipment so sensitive it could detect the heat differential between a white median strip and the blacktop road at ten thousand feet.

Jill was “wildly excited” when she heard the plane was on its way. But Ron, who was “very protective about letting me get my hopes up,” cautioned, “It’s just a machine, don’t put too much on it.”

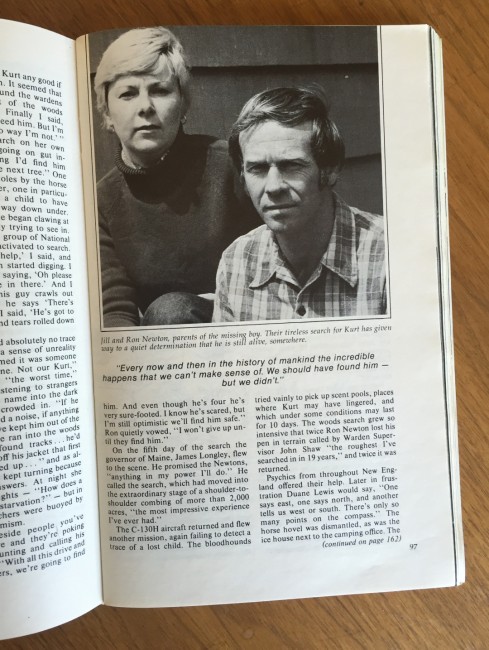

Even veteran woodsmen were in awe of Ron Newton’s quiet endurance as days and nights passed with him refusing to rest. “The responsibility was ours,” he’d say quietly. “The burden is ours to get him back.” On Monday, returning wearily from the woods at dusk, Ron tripped and fell heavily in a deep gully. His ankle turned bright purple and swelled to twice its size. Though ordered off his feet by a doctor, he continued to end a day’s woods search at his familiar post in front of the loudspeaker, calling his son’s name into the forest. In desperation, friends laced his coffee with tranquilizers. Wednesday night, his fourth night without sleep, the drugs finally took effect. His speech slowed and he sat gripping the loudspeaker close to his mouth, unable to speak, until finally his head dropped as he gave in to his shattering fatigue. “He was the toughest man I’ve ever seen,” said Duane Lewis. “Just unbelievable stamina.”

The C-130H gunship flew a three-hour mission Tuesday morning, failing to detect a trace of Kurt. The plane was hampered by low-hanging clouds and heavy rains that grew so bad searchers could not see their way in the woods and had to be pulled out. Hovering over the search area in the helicopter, Jill would call, “This is Momma. I want you to go to where you can see the sky. Come and wave to Momma.” As the rain and fog continued into the fourth day, hopes dimmed that Kurt could be found alive, and the strain on Jill was growing unbearable.

“If someone had asked me beforehand how I would have acted,” she would say later, “I would have said I’d go to pieces. But something happens to keep you going. You find reserves you didn’t know you had. I kept telling myself it wasn’t going to do Kurt any good if I wasn’t able to function. It seemed that every time I turned around the wardens were pulling Ron out of the woods because I was upset. Finally I said, ‘Look, I’ll tell you if I need him. But I’m going to cry. There’s no way I’m not.’ “

She preferred to search on her own with a few friends, “going on gut instincts. I kept thinking I’d find him whimpering behind the next tree.” One day she found some holes by the horse hovel that bothered her, one in particular large enough for a child to have crawled through and way down under. Lacking a flashlight, she began clawing at the ground, desperately trying to see in. Looking up, she saw a group of National Guardsmen recently activated to search. ” ‘I’ve got to have help,’ I said, and three or four of them started digging. I was panicky by then, saying, ‘Oh, please, God, he’s got to be in there.’ And I looked down and this guy crawls out from the hole and he says, ‘There’s nothing there,’ and I said, ‘He’s got to be,’ and he said no and tears rolled down his face.”

As days passed and absolutely no trace of Kurt was found, a sense of unreality flooded Jill. “It seemed it was someone else’s child, not mine. Not our Kurt,” she said. At night, “the worst time,” she’d rest fitfully, listening to strangers bellowing her son’s name into the dark, and the thoughts crowded in. “If he panicked, if he heard a noise, if anything the noise would have kept him out of the woods, … even if he ran into the woods why haven’t we found tracks … he’d surely have taken off his jacket that first day when it warmed up …” and, as always, the questions kept turning because there were no answers. At night she faced terrible thoughts — “How does a four year old face starvation?” but in the morning searchers were buoyed by her dauntless optimism.

“You walk beside people you’ve never seen before, and they’re poking and searching, hunting, and calling his name,” she said. “With all this drive and all these volunteers, we’re going to find him. And even though he’s four, he’s very sure-footed. I know he’s scared, but I’m still optimistic we’ll find him safe.” Ron quietly vowed, “I won’t give up until they find him.”

On the fifth day of the search, the governor of Maine, James Longley, flew to the scene. He promised the Newtons, “Anything in my power I’ll do.” He called the search, which had moved into the extraordinary stage of a shoulder-to-shoulder combing of more than two thousand acres, “the most impressive experience I’ve ever had.”

The C- 130H aircraft returned and flew another mission, again failing to detect a trace of the lost child. The bloodhounds tried vainly to pick up scent pools, places where Kurt might have lingered, and which under some conditions may last for ten days. The woods search grew so intensive that although Ron Newton twice lost his pen in terrain called by Warden Supervisor John Shaw “the roughest I’ve searched in nineteen years,” it was twice returned.

Psychics from throughout New England offered their help. Later, in frustration, Duane Lewis would say, “One says east, one says north, and another tells us west or south. There’s only so many points on the compass.” The horse hovel was dismantled, as was the ice house next to the camping office. The dump was bulldozed, and workers sifted through clumps of dirt. Teams of volunteers with shovels dug along the tote road. Finally John Shaw and Duane Lewis, haggard from constant twenty-two hour days, announced they were no longer appealing for volunteers. The search would continue, they said, until Wednesday, September 10, thirteen days after Kurt Newton’s disappearance. “We’ve done just about everything we can think of” they said. “Everywhere you go there’s marking tape and our footprints.”

The day the search was to end, the governor extended it two more days. “It’s the perplexity of the situation,” he said. “When you’ve searched that long and hard. there’s always the hope that this time we’re going to hit it.” It ended officially at dusk on Friday, September 12, in the woods by the dump, with twelve wardens, six state troopers, and seventy-five volunteers making a final, mournful shoulder-to-shoulder sweep. At the end, over three thousand searchers had taken part, and absolutely nothing had been found.

Ron and Jill Newton stayed two more weeks before returning to Manchester to put Kimberly, who had stayed with friends, into the first grade. They began weekend journeys to Chain of Ponds, two people in a woods that might as well have stretched forever. Duane Lewis returned as well, a solitary figure on overgrown tote roads that he hoped might still yield the most elusive tracks of his career. Years later he would be unable to spot a sneaker thrown carelessly on a river bank, or a torn shirt discarded on a roadside, without thinking about Kurt Newton. “Every now and then in the history of mankind the incredible happens that we can’t make sense of,” he would say. “We should have found him – but we didn’t.”

The Newtons posted “Missing” signs deep into the woods, warning hunters to report any unusual signs. And then the snow came, and Ron had his snowmobile to take him deeper into the backcountry until winter grew raw and even he was forced to say enough. By then they had decided that Kurt was not in the woods, that he never had been, that somehow he’d been taken and probably was still safe. With the tenacity they had shown from the beginning, Ron and Jill determined that if Kurt were to be found, it was up to them.

“From the beginning we never discounted the possibility that Kurt was abducted,” said State Police Lieutenant G. Paul Falconer, who headed the initial investigation, adding, “but there are no facts to indicate he’s not in the woods.” A team of investigators interviewed everyone known to have been at the campground, using polygraphs when in doubt. One camper reported that she had seen a white station wagon roar out of the campground leaving a cloud of dust in its wake shortly after the time Kurt disappeared. But no such car was registered at the campground, and nobody else reported seeing it. Upon further questioning the camper hedged: perhaps she’d been mistaken.

Experienced trackers reported they could find no evidence of recent vehicle traffic on the logging road beyond where Ron Newton had been cutting wood, the only road available for a “back-door” abduction. “With so many children available in the cities, why would a kidnapper come to one of the most remote campgrounds in the state, hoping to find a child riding a tricycle alone down a deserted road?’ asked State Police Detective Richard Cook, who assumed charge of the investigation, and who heads it today.

There was a grim report that a captive bear, often teased by local children, might have been released a few miles from the campground shortly before Kurt disappeared. A bear could have carried Kurt swiftly outside the area, experts conceded, but it was highly improbable that there would be a complete absence of signs.

The police sent teletype descriptions of Kurt throughout the United States and Canada. Soon Kurt Newton stared hauntingly from post-office walls in hundreds of cities. A call came from a man in Connecticut. He had returned from camping in the Canadian Rockies. There he had noticed a small blond-haired boy staring at him with a quizzical expression. He said he was struck by how nervous the boy and the man with him seemed with each other. He saw the same boy, he said fervently, on a Kurt Newton “Missing” poster. That same week a call came from Vermont. Two waitresses were sure they had seen Kurt in their restaurant. Detective Cook drove to Vermont and found that boy. It wasn’t Kurt.

There was an electrifying day four months after Kurt was lost. A call came from New Orleans that a small blond-haired boy of perhaps three or four had been found wandering in the French Quarter. He was very shy. He responded only to names with a k sound, like Kenny or Kurt. The Newtons raced to Boston to view a videotape of the child. But even as they watched it, certain he wasn’t their Kurt, the boy was identified as the abandoned son of an itinerant Missouri woman who was hitchhiking out west, and his name was Clifford.

Jill would wake up and admonish herself, “You’re being ridiculous. You’ve got to make up your mind. Either he’s in the woods or he’s with someone.” She went to Laconia, New Hampshire, for an interview with famed psychic Jeane Dixon. Dixon told Jill she knew about Kurt’s disappearance and had been meditating on it.

Jill said, “I told her the police felt very strongly he was in the woods. I was trying very hard for her not to tell me what I wanted to hear. She said, ‘No, I feel your son is alive.’ I said it was unbelievable to me that in ten minutes on a deserted road anyone would have had the time or the inclination to take him. She asked me if I had other children. I said, ‘Yes, a six-year-old daughter.’ She paused, then said, ‘No, I’m picking up your son’s vibrations. But he’s going to have to be missing you a great deal for me to pick up a direction. And it’s very easy to appease a four year old.’ “

It became Jill’s singular determination to “get Kurt’s picture to everyone in the United States and Canada.” At first the Newtons went “door-to-door, like traveling salesmen,” driving to Quebec City and stopping at every gas station and store to pass out posters. That experience exhausted them, and they returned convinced they must mount an unprecedented mailing campaign of mind-boggling proportions.

With help from friends in the printing trades, their basement soon overflowed with more than seventy-five thousand posters stacked into every conceivable space. They sent for telephone books from major metropolitan areas in the United States and Canada. Every night friends gathered, twenty and thirty strong, in the firehouse to confront a mountain of Yellow Pages. Ron bought stamped envelopes by the thousands. “Our home resembled a paper factory,” Jill said. Pictures of Kurt left the tiny Manchester post office for department stores and restaurants thousands of miles away.

Jill was troubled by the memory of her own response to such posters when she was a girl. “I’d see the pictures of wanted criminals and I’d say to myself, ‘Today I’ll see him for sure,’ and then I’d forget what they looked like. No matter how much you stick a child’s picture in front of people,” she fretted, “they can’t remember.”

Eventually, the Newtons considered the fact that soon Kurt would be school age and somewhere he had to go to school. After six months of nightly correspondence, they had compiled a list of every superintendent in every school district in the United States. “I couldn’t believe how many schools there are,” Ron said. Tables were set up in the firehouse, and again friends pitched in. They worked state by state, sending a letter asking that the picture be posted for two years, and including five posters to the superintendents. It took six months of nightly gatherings to finish, and then they began anew with Canada. Two years after Kurt pedaled away, their incredible campaign was over. They had spent well over $5,000 on mailing costs alone; by the end only a stack of one thousand posters remained in their basement. “When the last envelope went, we had the feeling we’d done everything we could,” Ron said. “Then all we could do was wait.”

Letters came back from everywhere, filled with sympathy and prayers, and many enclosed photographs of children in local schools. “We got some awful close resemblances back,” Ron said, and police in far distant places checked them out. Time passed. and the Newtons realized that soon a picture of Kurt at four would mean little to a teacher meeting him at six or seven. “Sometimes I think, if Kurt walked by me, would I know him?’ admitted Jill. “It’s a weird, panicky feeling.” They were left with the hope that Kurt would tell a teacher that he used to live in Maine and he used to have a sister named Kimberly and that one day he was taken away.

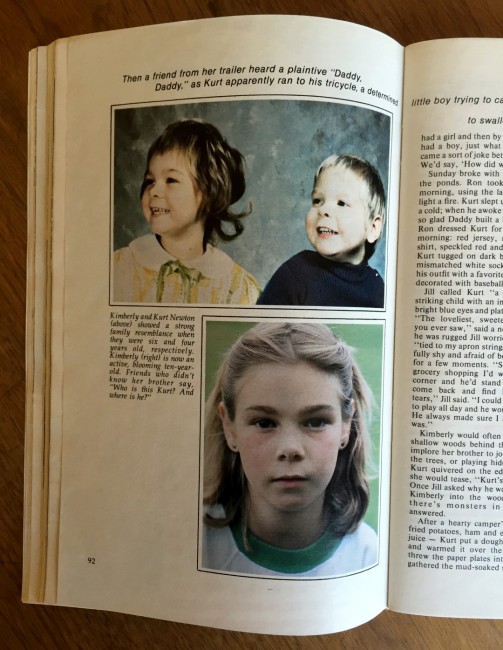

Four years after Kurt’s disappearance, a visitor to the Newtons would be struck by how normally they are living with this most abnormal of burdens. Jill has opened a beauty shop downstairs in their home, and has a growing number of customers. Ron works fourteen-hour days for the highway department, and on weekends putters around in his shop, planning improvements to their home. Kimberly is a bright, winsome girl of ten, who swings from the weeping willow in the yard, loves baseball, and complains that her mother doesn’t allow her to ride her bicycle in the street like her friends do. “Ron’s constantly telling me I’ve got to let her do more,” Jill said.

There are changes, of course. They have sold their tent trailer and no longer go camping. There is laughter in the house, and there was a trip to Disneyland, but Kurt is always on the edge of things. “Kurt’s name is always around our household,” Jill says. “We say things like, ‘Kurt had a pair of pants like that,’ or ‘Wouldn’t Kurt have liked that.’ A boy moved next door after Kurt was lost, and he kept asking Kimberly, ‘Well, who is this Kurt? And where is he?

“People who don’t know me say how many children do I have, and I say two, a ten year old and an eight year old, and I don’t think about it because I will go on expecting that someday he’ll walk through that door, even at fifty years old — until somebody proves to me that I’m wrong.

‘ I think your mind has to rest. Now we can take a big gulp and say, ‘Okay, now we’re going to forget about it for a while and have a good time.’ It’s never ever forgotten, really. I know it’s there, and I know I’ll come back to it, but I’ve learned to glide around it. To keep on going.”

On Sundays there are picnics outside, or at the lakeside cabin two miles from their home. “We were extremely close before,” Jill says, “and we’re closer now. Ron was quiet before, and he’s quieter now. It’s still hard for the two of us to talk about it a lot. It’s like we’re careful not to rile too much up. We’ve accepted and are coping with the way things are. But isn’t it incredible that after all that’s happened during these four years we don’t know any more than we did when we first missed him?”

They speak about plans to convince the President to establish an agency to help parents whose children are missing. They think their experiences in distributing Kurt’s picture would be invaluable to anyone in a similar dilemma. And they still seek ideas. “If anyone can come up with anything and give me an address of how I can do it, that’s what I want.”

After spending a weekend with Ron and Jill and Kimberly, two images remain, as bright as Kurt’s blue eyes that seem to bum from his pictures. It is a Saturday night, and Kimberly is sitting cross-legged on the old brown sofa in their lakeside camp. She is dressed in a pink bunny suit, and her lovely brown hair is brushed down her back. It is late and the light in the cabin is dim and she is sleepy, but she wants to finish reading her book. The name of the book is Donn Fendler, Lost on a Mountain in Maine, the dramatic true story of the twelve-year-old scout from Rye, New York, who, against great odds, survived a nine-day trek to safety from mist-shrouded Baxter Peak. “I wonder if that’s how it was for Kurt,” she says softly, and when she is finished, the happy ending tucked in her mind, she is ready to sleep.

On Sunday the table is set outside the Newtons’ home for a traditional Sunday dinner of roast pork and potatoes. It is sunny and a wind is blowing; there is debate whether to eat indoors or out. Their garden is planted and staked out, and Jill sits in the warm grass of late spring. “I really enjoy watching things grow,” she says. “But I’m so impatient waiting for the produce.” Across the yard Kimberly is laughing as she sails on her rope swing. Ron, who is camera shy, is finding things to do to keep from being photographed.

“You know,” Jill says, “in a way I feel fortunate. I have a prayer. And I have tomorrow. And tomorrow may bring Kurt.”

This story’s appearance in Yankee Magazine in 1979 prompted an enormous response from people who thought they might have information about Kurt Newton’s whereabouts; as of today, however, he has not been found.

MORE YANKEE CLASSICS

Christa McAuliffe’s Shadow

9/11 Started Here

The Killing of Karen Wood

The Long Silence of Lizzie Borden

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen