The Ghost of Andrew Wyeth

Andrew Wyeth is dead. He reportedly passed away peacefully in his sleep at the great age of 91. Had this been summer, he probably would have drifted away in Port Clyde, Maine, but, as it is winter, his final resting place was Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, the little hamlet where he was born in 1917. America’s […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanAndrew Wyeth is dead. He reportedly passed away peacefully in his sleep at the great age of 91. Had this been summer, he probably would have drifted away in Port Clyde, Maine, but, as it is winter, his final resting place was Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, the little hamlet where he was born in 1917. America’s most famous and most popular artist, Wyeth was also its most misunderstood.

Andrew Wyeth lived a charmed but cloistered life. His world was largely limited to the two poles of his existence – Chadds Ford and Maine, where the Wyeth clan owns properties in Cushing and Port Clyde, including several private islands. He preferred “going deep” to scattering his attentions far and wide. As such, he created internationally-known art out of the lives and landscapes of these two rural outposts.

Though he was a man of patrician bearing, great fame, and considerable wealth, Wyeth eschewed society, preferring the company of ordinary people. In Chadds Ford, he created what amounts to a visual novel out of the hard lives and hardscrabble farm of Karl and Anna Kuerner. In Cushing, he created a Maine sequel out of the lives of the spinster Christina Olson and her bachelor brother Alvaro. His single most famous painting, “Christina’s World,” is a bleak 1948 vision of the crippled Christina crawling up the hill to the weather beaten farmhouse she shared with her brother.

“Life is strange,” Wyeth once told me. “From the outside, things may look one way, but when you look inside, they’re very different.”

In my 20s, I had a reproduction of “Christina’s World” hanging prominently in my apartment. For some reason, I pictured Christina as a lovely young woman lying in the field. I didn’t get it at all. And that’s the thing about Wyeth. Most people, whether they revere or revile his art, miss the point. Everyone loves Andrew Wyeth. What’s not to like, right? But as I began to take an interest in contemporary art, first studying, then collecting it, and finally writing about it, I came to understand that Wyeth was generally looked down upon by the art establishment. His art was conservative, traditional, nostalgic, romantic, or worse. Sentimental.

I confess I slipped into that mindset for a few years, but in a maturation process I have come to understand as widespread, once I began to have confidence in my own judgment, I had to re-assess my rejection of Wyeth. He might paint as though the 20th century never happened, but, man, could that guy paint. And what looked like sentiment to jaundiced eyes attuned to irony was revealed as sincerity. If Wyeth’s world looked old-fashion, it was partly due to the finesse of his brushwork and partly to the fact that the dominant visual aspect of the Brandywine Valley of Pennsylvania is 18th century while the residual agrarian landscape of coastal Maine is very 19th century.

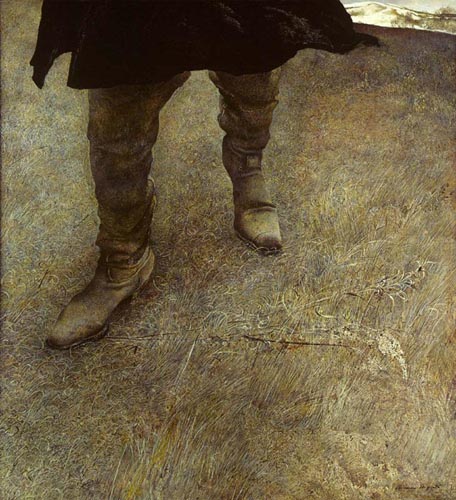

If you’re going to live a deep life rather than a shallow one, you have to embrace your roots. Wyeth was trained by his father, the great illustrator N.C. Wyeth, and when he came to paint his oblique 1951 self-portrait, “Trodden Weed,” he portrayed himself walking the land of his forebears wearing boots that once belonged to his father’s teacher, Howard Pyle. We all inhabit the past. We live among ghosts. And now Andrew Wyeth, who knew this better than anyone, is himself history.

For more Andrew Wyeth information and images, visit the websites of the Brandywine River Museum, Farnsworth Art Museum, or the official Andrew Wyeth website.

A great master.

I love art, majored in art, and fell in love with Andrew Wyeth’s work about 35 years ago. On a trip to NYC my uncle took me to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to see the Kuerners and Olsons exhibit and I was hooked. Seeing those grand paintings – with unbelievably detailed brushwork and color that spoke words, volumns, and reached out and grabbed something in me – it was an immediate love affair. I got the museum’s book that showed everything they exhibited and included an enormouse interview Wyath wrote speaking of the works, philosophy, family, and more is one of my treasures. The last painting in the viewing is “The Virgin.” There are no words to describe it’s impact. If you ever get a chance to see it – don’t pass it up.

Since then I still review that book, have kept the major magazine pieces on him (see TIME magazine, August 18, 1986 on “The Helga Paintings”), bought that book (“The Helga Pictures”) and have appreciated not only his art, but his dedication to painting his way, what he’s written, what he expresses, and his philosophies tremendously. I would call him one of America’s great institutions. That’s all.

Thanks for the information about “Christina’s World”. I have wondered about the girl in the painting from the first time that I saw the painting ( about 50 years ago ). It did occur to me that she was crippled, but I was not sure.

Thanks, again.

Edgar, Your article about Wyeth for Down East (April issue?) was terrific. In terms of artists being popular/misunderstood, I wonder if comparimg Wyeth to Robert Frost is appropriate. Their work can be appreciated on so many levels. On the surface, the simplicity of rural NE (and Penn., in the case of Chadds Ford) is what is communicated, but there is so much more.

I don’t know why but Wyeths,”christina’s world” has forever been one of my few favorites in paintings,maybe because it does outline real life or struggles in life……all uphill…and at times rather lonely……….I do love his painting……..