Big Plan on Campus

Olin College, a little engineering school in Needham, Massachusetts, is retooling higher education.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanOn a wintry Saturday in the Academic Center of Olin College, 16 teams of high school seniors raced to build a device that could be lowered from a balcony to scoop up a plastic egg from a paper nest 10 feet below and deliver it to safety in a second nest nearby. Their only supplies were grab bags of paper clips, duct tape, string, pipe cleaners, balloons, rubber duckies, and other random items. The room thrummed with the energy of feverishly brainstorming teenagers. The five-person teams had been working for 90 minutes, and time was running short.

“Thirty minutes!” came the call from the Olin students running the competition. “Thirty minutes to complete your contraption!” A nervous thrill went through the kids. They had only just met one another, and a lot was at stake: They all were trying to get into Olin, an engineering school of 350 students in Needham, Massachusetts, whose radical emphasis on collaboration and experiential learning just might transform higher education.

As rock music pounded from portable speakers, the high schoolers used paper clips to attach popsicle sticks to plastic bags, and twisted bits of yarn together to make 10-foot lengths of string. The challenge required each team to work with a partner team, but the only communication allowed between them was via handwritten note, delivered by Olin students on scooters. To raise the difficulty level, the Oliners redacted words at random before delivering the notes. One team got around this by using rubber duckies to communicate in Morse code. Dot-and-dash squeaks cut through the din.

Surveying the chaos approvingly was Emily Roper-Doten, Olin’s dean of admissions. There’s a method to the madness, she told me. Students apply to Olin by completing the Common App, the standard online application used by almost all schools in the United States, but then things get weird. Of those applicants, 250 are invited to one of three Candidates’ Weekends, and how they handle those two days of design challenges, group exercises, and interviews will determine whether they are offered one of the 85 spots in Olin’s next class.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Candidates’ Weekend begins with a design challenge—like the one we were watching—that is always conceived and run by Oliners. “The tradition of it being student-designed is partially to communicate to the candidates that students have a powerful role here,” Roper-Doten explained. “You are more than 1 percent of your class, and you can influence who’s coming here next.” She was particularly pleased that this year’s challenge hinged on the interaction between partner teams. “That’s impressive. It shows an awareness of their own educational experience. We talk a lot about teaming. And a lot of teaming is communication.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

The candidates aren’t evaluated on the success of their contraptions. The key would come later, in the interviews and group exercises. Would they use their experience to meld into a team? Would they come up with constructive ways to tackle the rest of the weekend’s challenges? “We’re looking for creativity, but a lot of it is about interpersonal skills,” said Roper-Doten. “How do they respond when their idea isn’t the winning idea? Do they contribute, or do they just shut down? That’s something we wouldn’t see in a regular admission process.”

Candidates’ Weekend also serves to give applicants a taste of Olin culture. Students who thrive in a traditional lecture environment might not be happy at Olin, which is the first engineering school in the world to be centered on a project-based “do-learn” model. The idea is that life is not a series of tests with correct answers, but rather a continuous stream of poorly defined challenges in which you have to cobble together something that works.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

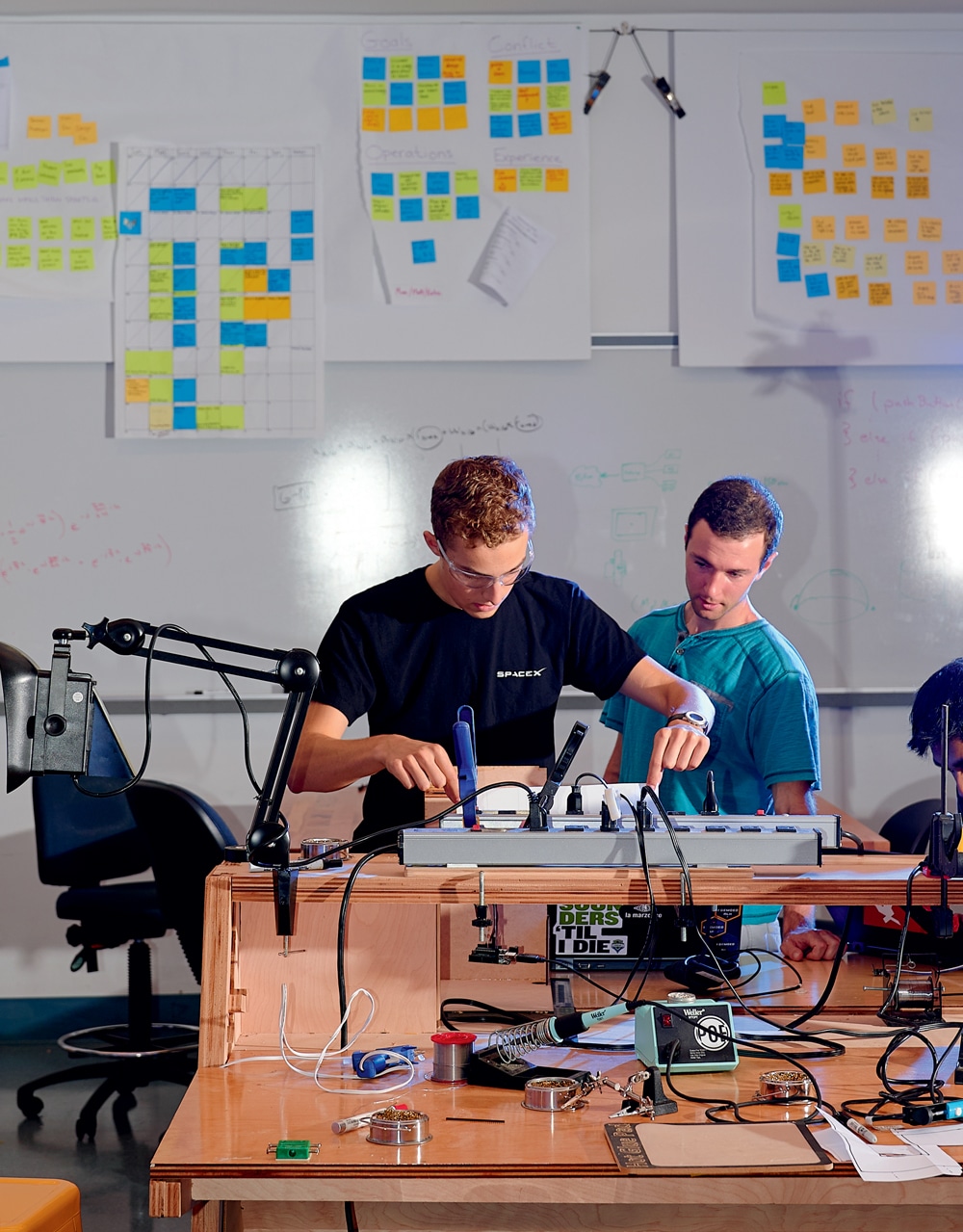

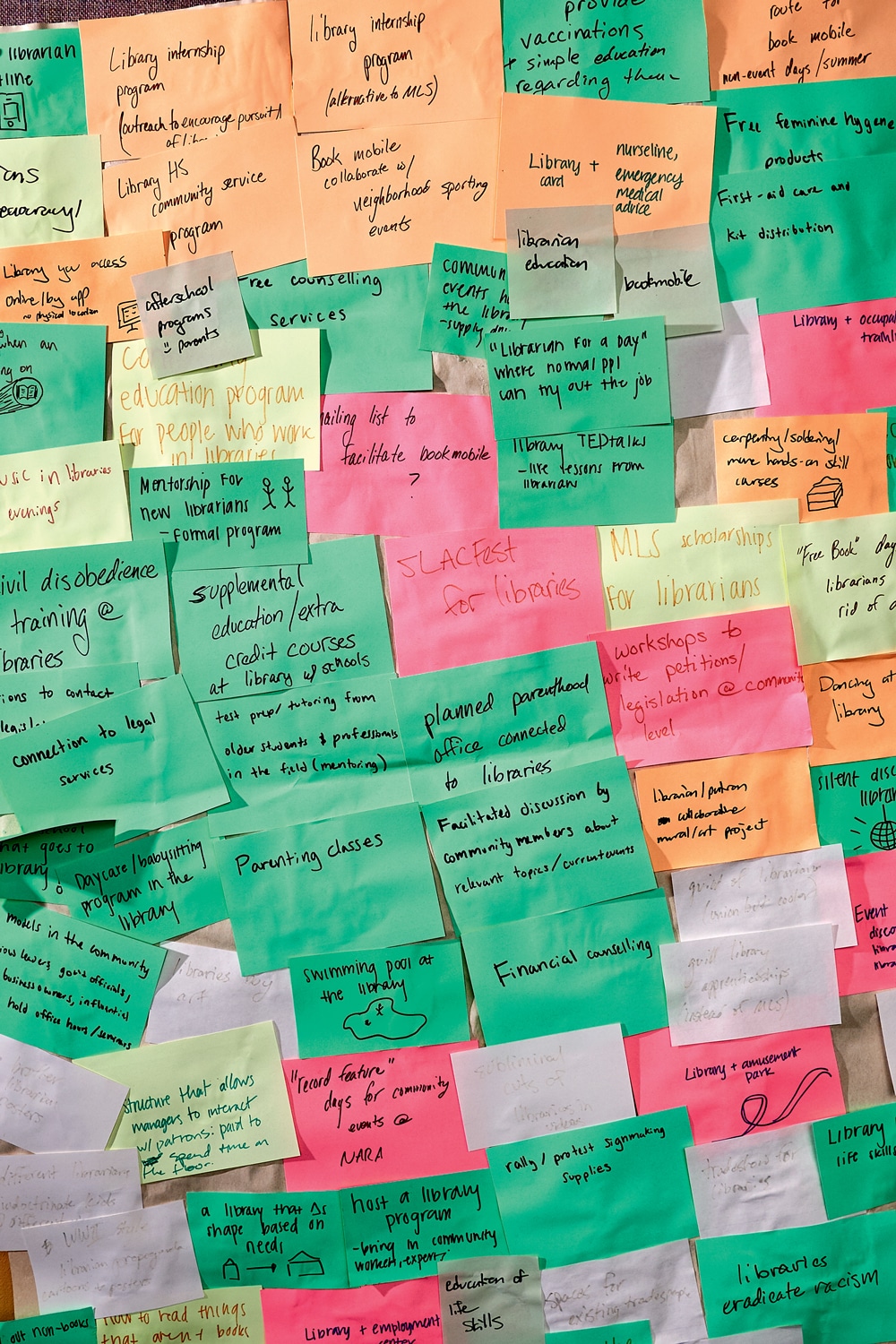

Tests and textbooks are few and far between at Olin. Instead, students tackle dozens of Candidates’ Weekend–style projects, both solo and in teams. They might have to build a heartbeat monitor, a facial-recognition app, or a system that encourages coffee shop customers to choose reusable cups. By their senior year, they will take on actual engineering projects for companies such as Amazon, GE, and Mitsubishi.

Oliners are trained to immerse themselves in the dynamics of a problem or system, to understand the goals and the needs of the people involved, and to explore as many crazy ideas as possible before settling on a plan. Known as “design thinking,” it’s an approach that can be equally handy whether your problem is how to land a probe on Mars or how to make an affordable T-shirt without a sweatshop. And though it was originally created for engineers, many educators believe design thinking should be a part of every citizen’s schooling.

“Some of the lessons we’re learning at Olin have no business being restricted to engineering,” says Rick Miller, Olin’s president. “They work just as well for integrating philosophy or any other discipline.” Miller is not alone in this opinion. In an influential 2015 article, The Chronicle of Higher Education asked, “Is Design Thinking the New Liberal Arts?” Now hundreds of institutions are making the pilgrimage to Olin’s door to find an answer to that question.

—

Olin College was created from scratch 20 years ago by the Olin Foundation, which believed that a new educational model was needed to produce more bold, socially conscious innovators. Engineer, after all, stems from the same word as ingenuity. But traditional engineering programs, which submit students to years of numbing physics and calculus before any engineering takes place, were not producing the new Leonardos—and the Apples and Amazons of the world were making that clear. We no longer need Cold War warriors who can calculate all day, they said. We need people who can create and communicate.

For decades, the foundation had funded programs at science and engineering schools to spur that change, but it found that tenured professors and entrenched departments were not about to reinvent their entire system. So in 1997, it tried a Hail Mary: It committed all $460 million of its endowment to the creation of Olin College and put itself out of existence. Its statement of purpose read, “We see a future in which an undergraduate engineering education becomes the true ‘Liberal Education,’ i.e., an education which liberates one to lead a personal and professional life of full citizenship in one’s local, national, and global communities.”

The college was built on 75 acres beside Babson College, a well-known business school located between Needham and Wellesley. The location was not coincidental: Olin students round out their educations with entrepreneurial classes at Babson and humanities classes at Wellesley College.

To run the college, Olin hired Rick Miller, the University of Iowa’s dean of engineering. Miller had become concerned that rigid university structures prevented engineering students from receiving well-rounded educations, so he jumped at the chance to head up a school with no academic departments and a mandate of constant experimentation. He has been Olin’s president ever since.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

The college opened in 2001, offering free tuition as a way to woo top candidates. With fewer than 1,000 alumni, the oldest of whom are in their mid-30s, it’s deeply reliant on its substantial endowment. When that took a hit in the Great Recession, the college was forced to begin charging half tuition, though it still meets 100 percent of the financial need of all students.

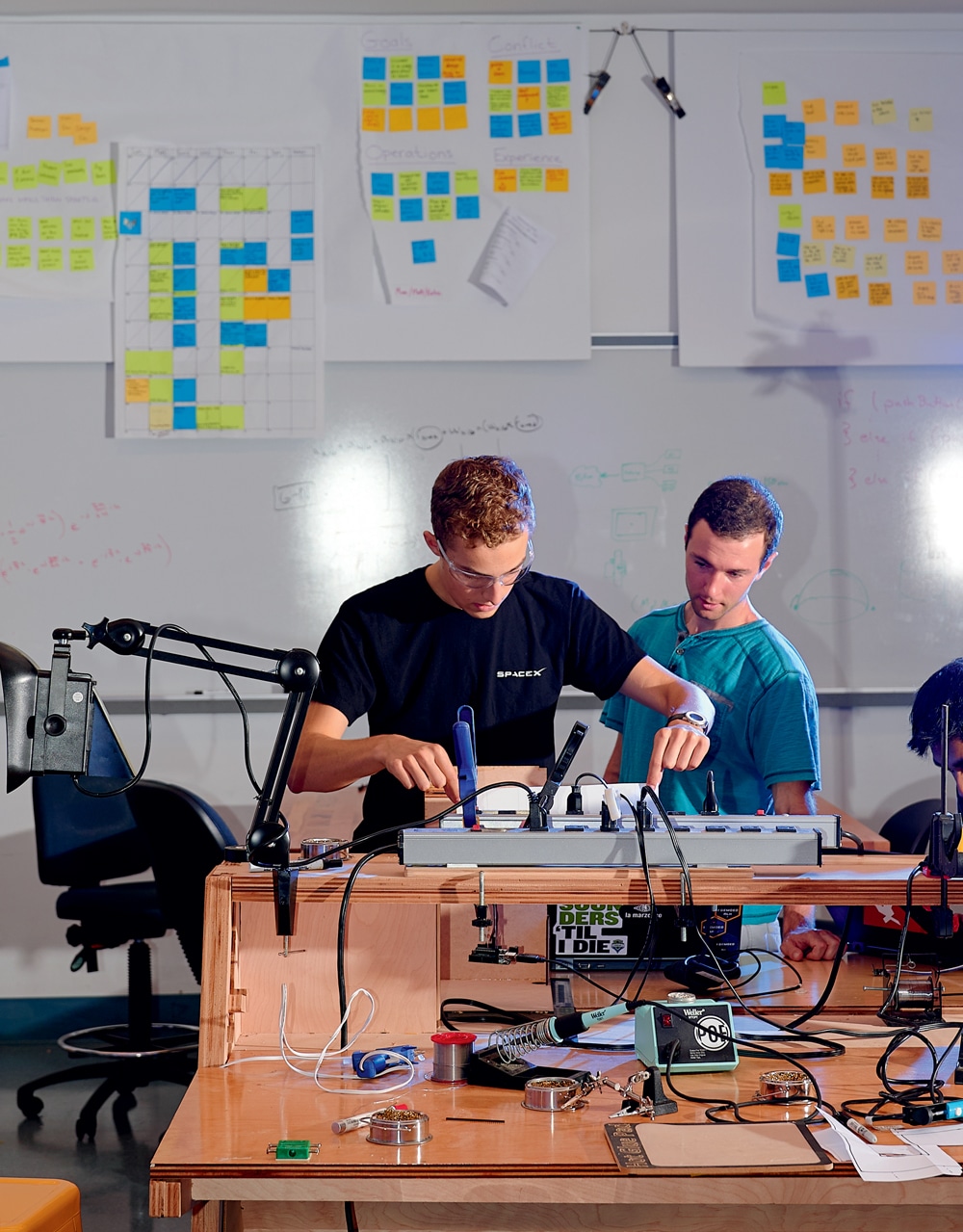

Olin College does not feel much like a college. There’s no ivy, no quad, no red brick buildings. The heart of campus is a curving, postmodern four-story glass oval that would be right at home at Google or SpaceX. As I walked around, people popped in and out of buildings carrying abstract sculptures and Styrofoam boats. In the robo lab, a student was playing chess against an automaton. Experimental aircraft hung from the ceiling. In a classroom wallpapered in sticky notes, Oliners were sprawled across tables and floors, designing insectlike “hoppers” that had to jump many times their own height. In one set of dorms with high ceilings, the kids had suspended their beds from the top and installed a movie theater and a milkshake shop in the spaces below. People danced on the green, twirling fire sticks. It was like a cross between Boeing and Burning Man.

Was that good? It felt invigorating, but four years of Burning Man could get a little old. I asked Maggie Jakus, the Olin senior who was guiding me around campus, if there was indeed a method to the Olin madness.

Jakus told me she’d been attracted to Olin’s progressive approach and its 50/50 gender balance, which is unheard of for an engineering program—but after attending Candidates’ Weekend and being offered admission, she instead chose Cooper Union, a traditional engineering school in New York City. “I got a weird vibe from Olin,” she admitted. “They were like, ‘Look at us! We’re so fun and quirky!’ This guy kept telling me about Doctor Who. Personally, I don’t care about Doctor Who.” Then there was the size and location. “I grew up in downtown Chicago, and this felt like the middle of nowhere.” Indeed, size is the top reason that people either do or don’t attend Olin. A serene oasis on a leafy hillside far from the nearest store, it can come across as wonderfully bucolic or eerily quiet, depending on how you roll.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Jakus was thrilled to be attending college in the heart of Lower Manhattan, but her enthusiasm faded as soon as classes began. Traditional engineering programs put students through coursework and tests designed to weed out all but the most technically oriented. Jakus found it frustrating. “It was just math for the sake of math. I memorized a lot of equations, and I still don’t know what they mean. My calculus class was just proofs and theorems. The exam would be, ‘State this theorem.’ There was clearly no application.”

Jakus was also disappointed by the male bias of the professors and the student body, which is common in engineering programs. “There was an attitude that this was a man’s world,” she told me. “The physics professor would say things like, ‘Well, the reason there aren’t as many women in STEM is because they aren’t as good at math.’ I thought, This is not how I want to spend my life.”

Over winter break, Jakus messaged a girl she’d met at Olin’s Candidates’ Weekend. “I asked, ‘Is it all a bunch of weirdos watching Doctor Who and unicycling?’ And she said no.”

Jakus switched to Olin after her first year. She immediately liked the hands-on approach, and though she still finds the setting and social life a bit sleepy, she even came to appreciate the size. “It does mean that you actually care about people and are willing to listen. People interact in ways I haven’t seen elsewhere.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Jakus realized it was paying off during summer break, when she interned at a manufacturing facility alongside an engineering student from a traditional school. “She had a much harder time doing basic things, because she wasn’t used to there being no answer,” Jakus told me. “She was more hesitant to just put herself out there and take a risk, which is something that I’ve definitely learned to do at Olin. She wasn’t big on asking for help, and all we do at Olin is poke each other and ask, ‘How do you do this? How do you do that? How’d you get yours done?’”

—

So does it work? Olin still hasn’t graduated enough students to really tell. But there are some tantalizing signs that something important is happening. One is a 2017 study by Lee Edwards, an Olin graduate who is now a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley, titled, “The College That Produces Founders at Five Times the Rate of Stanford.” Edwards pointed out that although Stanford is frequently cited as the university that produces the most startup founders, in terms of percentage of graduates who launch new ventures it ranks a distant third (0.51 percent) behind MIT (0.75) and Olin, 2.77 percent of whose graduates have founded startups. In explaining this success, Edwards cited the same culture of risk-taking and experimentation that Maggie Jakus had mentioned to me, as well as Olin’s 50/50 gender balance. (Companies with at least one female founder tend to outperform the crowd.)

Numbers like that are spurring educational leaders to take a very close look at Olin. Since 2010, more than 830 schools, many from the developing world, have visited Olin to study its program. “Two or three times a month,” says Rick Miller, “people come with a blank sheet and a big checkbook and say, ‘We’re planning to start a new university in our country. How do we do that?’”

In 2018, MIT’s School of Engineering launched an initiative to create a vision for the future of engineering education, for both itself and other institutions. It highlighted Olin as the model, for its hands-on approach and its emphasis on ethics and social engagement. Yet it also noted Olin’s boutique size. It’s one thing to run a Candidates’ Weekend for 250 applicants, but just try it with 5,000. And you can’t change the world 85 graduates at a time. As one of the consultants pointed out, “The next phase in the evolution of engineering education is for the rest of us to figure out how we can offer this type of quality of education at scale.”

But can you? What I saw happening at Olin was all about its smallness. It’s a pattern I recognized from a lifetime spent in small New England towns, so it seemed entirely appropriate that’s where Olin had sprung up.

In a large university or a big city, it’s easy to opt out: Whatever need arises, whether it’s a concert to be played or a building to be designed, you just assume that someone better qualified—some expert—will take care of it. In fact, you don’t dare screw it up. The system is too large and complex to grasp, and so you find your specialty and become a cog.

Not so in the small town. Who’s going to take that role in the theater production, if not you? Who’s going to rebuild the grange hall? Teach soccer? Join the select board? Fix that lawnmower? Throw that party? What’s the worst thing that could happen?

New England towns make well-rounded citizens because you see how all the pieces of the puzzle fit together, and because you have to be quite a few of those pieces. Everyone pitches in and learns that with a combination of collaboration and hands-on learning, you can tackle pretty much whatever comes along. And occasionally, in the midst of making it up as you go, you stumble into greatness.

Olin struck me as the continuation of that long New England experiment, from the free thought and self-reliance of Emerson and Thoreau just a few miles up the road, to Vermont’s John Dewey, the champion of progressive education, who tried to move America away from European-style rote learning and toward a participatory style of education. Every school, Dewey wrote, should be a form of “embryonic community life, active with types of occupations that reflect the life of the larger society and permeated throughout with the spirit of art, history, and science. When the school introduces and trains each child of society into membership within such a little community, saturating him with the spirit of service, and providing him with instruments of effective self-direction, we shall have the deepest and best guarantee of a larger society which is worthy, lovely, and harmonious.”

Dewey never was able to push American education where he thought it needed to go, and he never would have imagined that an engineering school would be the place where his philosophy would bloom.

He also would’ve been a little bit creeped out by the notion that design thinking might be the new liberal arts. As was I, having participated in enough design workshops to know that they can sometimes feel like the Cult of the Sticky Note.

There’s a lot to be said for the old liberal arts. I like Boeing, and I like Burning Man, but I also like Brontë, Bergman, and Buddha. It’s not the worst idea to get a firm grounding in other people’s ideas before you start reengineering society.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

And yet, I could easily see how every liberal arts student could benefit from a dose of the team-centered, project-based training being taught at Olin. The classical artes liberales were the suite of skills and knowledge sets needed to become a well-informed and constructive member of society. But what skills does society need today? Who do I need in my small town?

Well, I’d want the Donald Hall types, writing curmudgeonly poems and thumbing their noses at design thinking from their defiantly unmodern farms, but I’d also want the Leonardo types, who can reimagine a city so that air and ideas flow freely, or look at a feather and be inspired to build something beautiful and new.

—

In other words, I’m pretty sure I’d love to have these kids in my town. As I watched them in the design challenge, attaching their final lines and tightening their ties, I thought of barn raisings and volunteer fire departments. I thought about their voices at Town Meeting Day.

“Ten minutes!” the Olin ringmaster shouted. “Finish your contraptions!”

And then it was time. Rooted on by a crowd of students, teachers, and parents, the high schoolers took turns lowering their inventions from the balcony to the nest 10 feet below. They had three minutes to lift the egg and deposit it in the higher nest.

It wasn’t easy.

A plastic cup with a cardboard hatch bumped the egg but couldn’t scoop it up.

A cardboard box festooned with sticky tape lifted the egg easily, but no amount of shaking could dislodge it into the upper nest. Time expired, and the crowd groaned.

The rubber ducky team had fashioned a hammock out of paper, its four corners attached to strings, so they could operate it like a marionette. After their partner team cleanly knocked the egg into the hammock with a wrecking ball made from a wire filament spool, they lifted the hammock above the second nest, crossed two corners of the hammock to form a spout, and lowered that end toward the nest. The egg plopped safely inside, and the crowd cheered.

Overall, only a few teams successfully rescued the egg, but it didn’t matter. Several Oliners proudly cited Yoda’s advice to Luke Skywalker: “The greatest teacher, failure is.” They had just shared two hours of pure creativity, and they were already bonding. A few of them may even have started to wonder if this was what college—and life—could be like.

Rick Miller says Olin was always meant to be an ongoing experiment. To do that, it has to stay small and nimble. It doesn’t need to be an exact model for other universities; it just needs to light the way. “If higher ed is this aircraft carrier stuck in the harbor, Olin is a tugboat on the bow,” Miller says. “Our job is to reorient higher ed a few degrees port or starboard, not 180 degrees. Even 10 degrees could make a really big dent in the universe.”

Still buzzing from the design challenge, the candidates headed to the dining hall for lunch with their newfound friends. From there, the afternoon would be filled with individual interviews and group exercises, and the evening with story slams and art performances.

As I watched them go, I couldn’t help but feel hopeful. I didn’t envy them the world they would face, with its devilishly complicated problems, but they seemed as if they were looking forward to taking a crack at it. Maybe they could change the world 85 graduates at a time. At the very least, they were going to have a lot of fun trying.

Fascinating article about an equally fascinating college. I feel so fortunate that my son, class of 2020, attends Olin. The school has engaged my son, helped him grow beyond anything I had imagined, and–oh, yes–helped him take a deep learning dive into computer science. Olin’s professors and administrators have always made my son feel like he is an important part of a community of scholars doing important work both for themselves and for the wider world.

Excellent article. Amazing approach for the process of acquiring new skills for the phase called “life.” The geographical setting is perfect choice for this new approach of learning to learn. As a senior manager in a large aerospace company I spent a week at Babson college (next door to Olin) with other managers brainstorming new directions for the future of our company. Perfect place with unusual vibes to think unconstrained by conventional approaches.

Olin, you go!

As a recent Olin College graduate, I’m very pleased with the emphasis that this article placed on agency and community. The outside world can seem large and deeply entrenched in its ways, but living and learning in “the bubble” taught me to speak up, question the current order, and see change through. The close community first attracted me to Olin, and since graduation my neighborhood and workplace have provided opportunities to get involved. New England towns are not unique in community collaboration, but they do it well!