Another Year of Mercy | Mary’s Farm

At times, starlight can illuminate what is truly important.

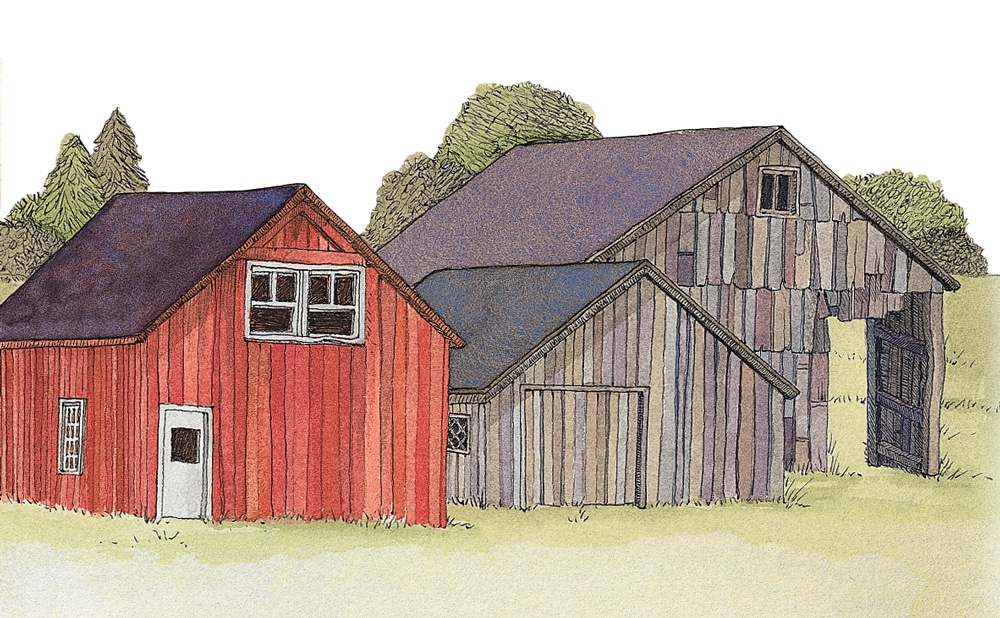

I’ve been told that the barn behind the house here is older than the house, which dates to 1762. Usually a family builds the house before the barn, though I suppose there are always exceptions, and no one was recording what Benjamin Mason did when he came here from Massachusetts in that forbidding, pre-Revolutionary year. Whatever happened with the house, I know for sure that the barn is older than this nation.

The building is tall, 30 by 45, and built on the ground. Inside, the timbers that support the structure are blond, wide at the top and tapered toward the bottom: gunstock posts made of chestnut. The tenons that connect the posts and the beams are big as corncobs, and they, too, are still light-colored, as if they were hammered in there yesterday.

Stepping into this barn is like stepping into an American history book. In there, I cannot help but think of the men who carved these posts out of trees, which grew, undoubtedly, very near to where the barn now sits. On the ground floor, there are two big windowless box stalls on one side and three smaller ones, each with a window looking east, on the other. In the center is a wide aisle that runs the length of the building—at the ends are doorways broad enough to drive a wagon through, which I’m sure was what happened most every day, the horses harnessed and hitched in the shelter of the barn and then driven out into the field, where hay or corn was picked up and brought back in through the other side. In this barn, roosters strutted, hens pecked, horses snuffled, cows were milked, and hay was thrown aloft. Generations of farmers stamped snow off their boots or wiped sweat from their brows, entering the building where their business took place, every day of the year.

It’s quiet now. Leaning as it does to the north and east, the barn has taken on a poetic profile, the sort that photographers and painters love to capture. Inside, the stalls harbor many things. One stall is piled with a collection of shutters and windows, likely saved from the last renovation, which I believe was in the 1950s. Another has boxes of saved magazines, all of them yellowed and swollen with years of sun and moisture, and yet another has a hodgepodge of old wooden kitchen chairs and an enamel kitchen stove, missing the lids.

Since I bought Mary’s Farm five years ago, I’ve managed well with the house, some months counting out my last nickels in order to get done what needs to be done. But the barn has suffered. I’ve been able to take only two swipes at saving it, more triage than repair: When the wide expanse of the back doorframe began to sag, a metal bar was hastily wedged underneath. And in the corner afflicted with dry rot, we cinched the buckled post back upright using a chain and a come-along, which remain in place. These measures may buy time until I can afford more.

Winters are what bring these structures down. The winds and the heavy snows combine to defeat their heritage. All winter, I look out my window to the barn and say silent prayers. In April, I watch the snow retreat and whisper thanks for another year of mercy.

Because of what the barn has to say, I want it to live another century. I dream of sheep in the stalls, the fragrance of lanolin and hay and manure scenting the aisle, and red-backed chickens in the coop, muttering and squawking and flapping when I walk in with the grain.

This essay first appeared in Yankee’s April 2003 issue. Edie Clark’s books are available at edieclark.com.