A ‘Very Impressive Rock’ | Madison Boulder

If you’ve ever wondered about the power of glaciers, pay a visit to the Madison Boulder.

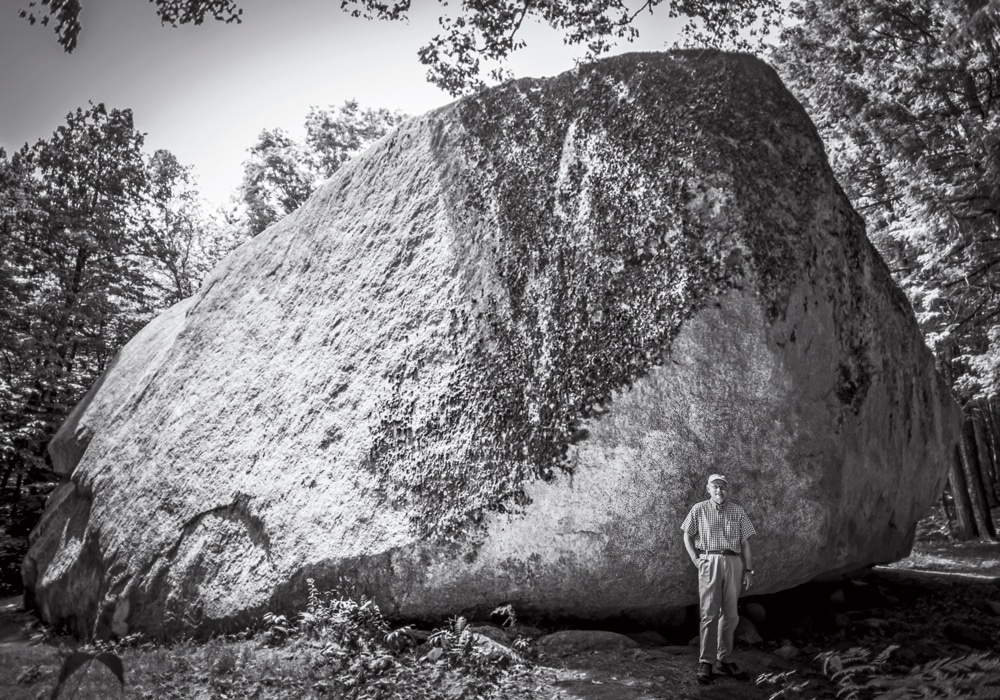

Friends of the Madison Boulder president Brian Fowler at the ancient slab, which not only towers over him but also extends another 10 to 12 feet underground.

Photo Credit : Michael SeamansNobody stumbles upon it. Or over it, for that matter, even though it’s been hunkered in the New Hampshire woods for the past 15,000 years.

My husband and I first learned about the monster rock known as the Madison Boulder, “the largest glacial erratic boulder in North America,” in a book about stone walls. Just from the description we already knew that no farmer had ever attempted to pry this specimen free and lug it to his boundary wall. The mention of the boulder was obviously for show, an extreme, something to elicit our sympathy and awe: Look at what these yeomen had to contend with!

But “largest glacial erratic boulder in North America” also elicited our imagination. Oh c’mon, how big? we wondered.

In early May, we left northern Vermont and drove east, across the Connecticut River into New Hampshire, surging up and over the White Mountains, cruising through North Conway’s fairway of motels and outlet shops, then poking along increasingly modest roads to reach the town of Madison. We passed a gravel pit, some small bungalows, and a recycling center. Could there really be a colossal rock near here? Finally, we rounded a corner and saw the sign: Geological Park.

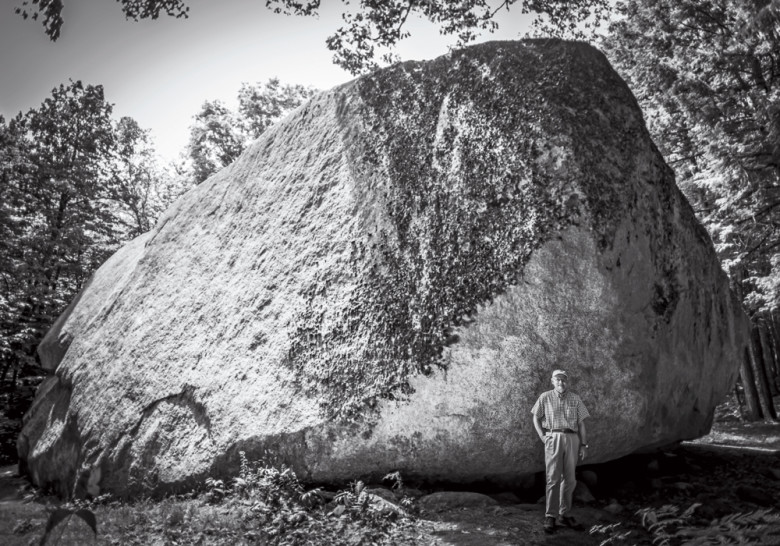

Photo Credit : Michael Seamans

After traveling two and a half hours, a distance of 120 miles in our Chevy, we had arrived in the vicinity of a boulder that had also made a voyage—one that took about 5,000 years, over the distance of a few miles, while trapped in a glacier.

Its chilly vehicle gave the boulder status as an “erratic,” which is the term used to describe any rock that thanks to glacial transport is constitutionally different from the rocks surrounding it. In designating the boulder a National Natural Landmark in 1970, the Department of the Interior heralded its transit as illustrating “the power of an ice sheet to pluck out very large rocks of fractured bedrock and move them substantial distances.”

A sign in the empty lot promised an easy 15-minute walk to the boulder. At scarcely the five-minute mark, I saw what looked like a slate barn roof in the distance and wondered aloud if it was maybe a three-story rangers’ quarters. “No, that’s it,” my husband said, just as we reached a clearing. The pamphlet we’d picked up in the parking lot described a “very impressive rock.” Oh yes.

The boulder’s dimensions—83 feet long, 23 feet high, and 37 feet wide—convey its enormousness, but how to account for its … sentience? The loafing rock emanates a presence, a heavy serenity. It seems like a petrified leviathan, with lichens freckling its flank like barnacles. At an estimated 5,900 tons, this behemoth of Conway granite in fact equals 35 blue whales.

I studied the boulder’s base, finding vole holes and violets and white-petaled stars-of-Bethlehem. In the distance, an ovenbird trilled; close by, a mosquito grazed my neck. All this delicate life, living with and beside the hulking rock.

Meanwhile, my husband prowled the circumference. When I found him on the far side, he was peering at some spray-paint iconography scrawled onto the boulder’s surface. Then his eyes traveled upward, and he fixed his gaze on the boulder’s crown. “Wouldn’t it be cool to see what’s up there?”

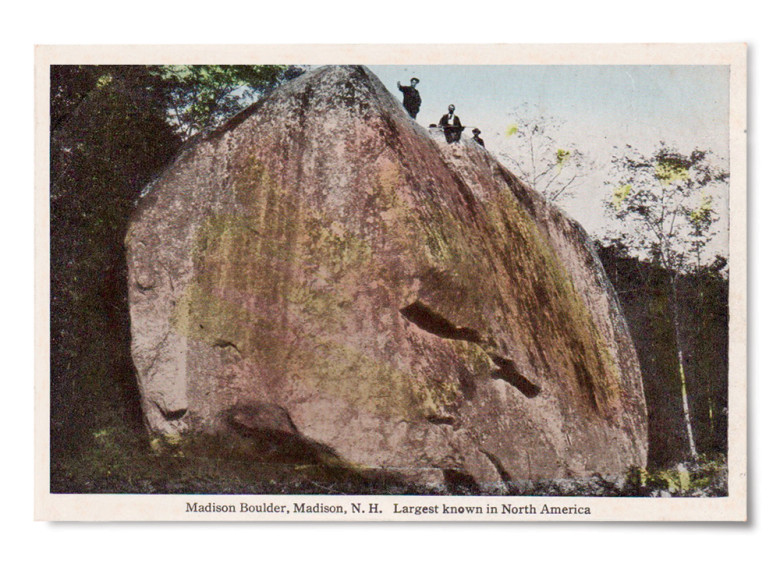

A picture in A Brief History of Madison, published in 1925, features two gentlemen who did exactly that. They are standing on the boulder’s pate, grinning. According to Brian Fowler, president of the Friends of the Madison Boulder, some of last century’s visitors brought chisels and mallets to inscribe their initials on the top of the rock, which they reached via a staircase erected along the back side. However, by the 1950s the staircase had largely deteriorated, and nowadays ambitious visitors lean tree limbs and trunks against the boulder to try to shimmy up. The advent of spray paint, it seems, has made leaving a signature far easier, something Fowler laments.

“There’s a segment of our society that needs to express itself,” he said. It’s a primal segment, I think, one that harks back to our prehistoric ancestors’ making unmistakable marks on rock for us to discover. Nevertheless, it’s also directly at odds with the Friends of the Madison Boulder, which has raised thousands of dollars to sandblast said expressions off the rock’s front side, restoring its appearance to perhaps that of 20,000 years ago, when the Wisconsin glaciation was in full swing.

We circled around to the boulder’s front. My husband stepped back, squinting at the rock, there in a clearing surrounded by the infant leaves of maple and beech, as if trying to imagine how it had foundered here. And so I reprised the history lesson that Fowler, who is also a trained geologist, had offered.

In 1878, Charles Hitchcock led the team that created the first geological map of New Hampshire, which included the Madison Boulder. A geology professor at Dartmouth College, Hitchcock also was the first to propose that the boulder had been delivered by glacier to the valley floor. (The common thinking was that epic floods had rearranged big rocks across the state’s terrain.)

Since Hitchcock’s time, surficial geologists have further described how the boulder arrived: During the last ice age, an advancing glacier knocked a chip off the old block (of exposed granite) and sleighed it “downstream.” This chip likely came from the Whitten Ledge, a formation standing a mile and a half to the northwest; in his years of exploring the area, Fowler has noticed that the mineral structure of the boulder “matches up perfectly” with that of part of the ledge.

For a few thousand years, this dislocated granite chunk was suspended in ice. But about 15,000 years ago, the glacier began to melt and gradually release its debris, and—as Fowler put it—“down she went.”

And down she remained—while across the globe, our Stone Age forebears were on the verge of domesticating sheep, soon to be followed by cows, and grain farming, which was about to grow by leaps and bounds due to a new tool called the plow. Yet innovations like chicken farming, horseback riding, and writing were still a few millennia down the road.

And there she sat—while humanity inched toward omelets, cavalries, and magazine publishing.

And here she still sits—this humongous heirloom from prehistory, persisting.

The Madison Boulder Natural Area is located at the end of Boulder Road, off Rte. 113, in Madison, NH, and is open to visitors year-round.

Julia Shipley

Contributing editor Julia Shipley’s stories celebrate New Englanders’ enduring connection to place. Her long-form lyric essay, “Adam’s Mark,” was selected as one of the Boston Globes Best New England Books of 2014.

More by Julia Shipley