Their Voices Carry Far | Pihcintu Multicultural Chorus in Portland, Maine

By bringing together young immigrants in song, this Portland, Maine, chorus offers a life-changing experience for performers and audience alike.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan“Even though we are only a tiny chorus, we try to give people hope of peace.” —Natalia, age 13, from Angola

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

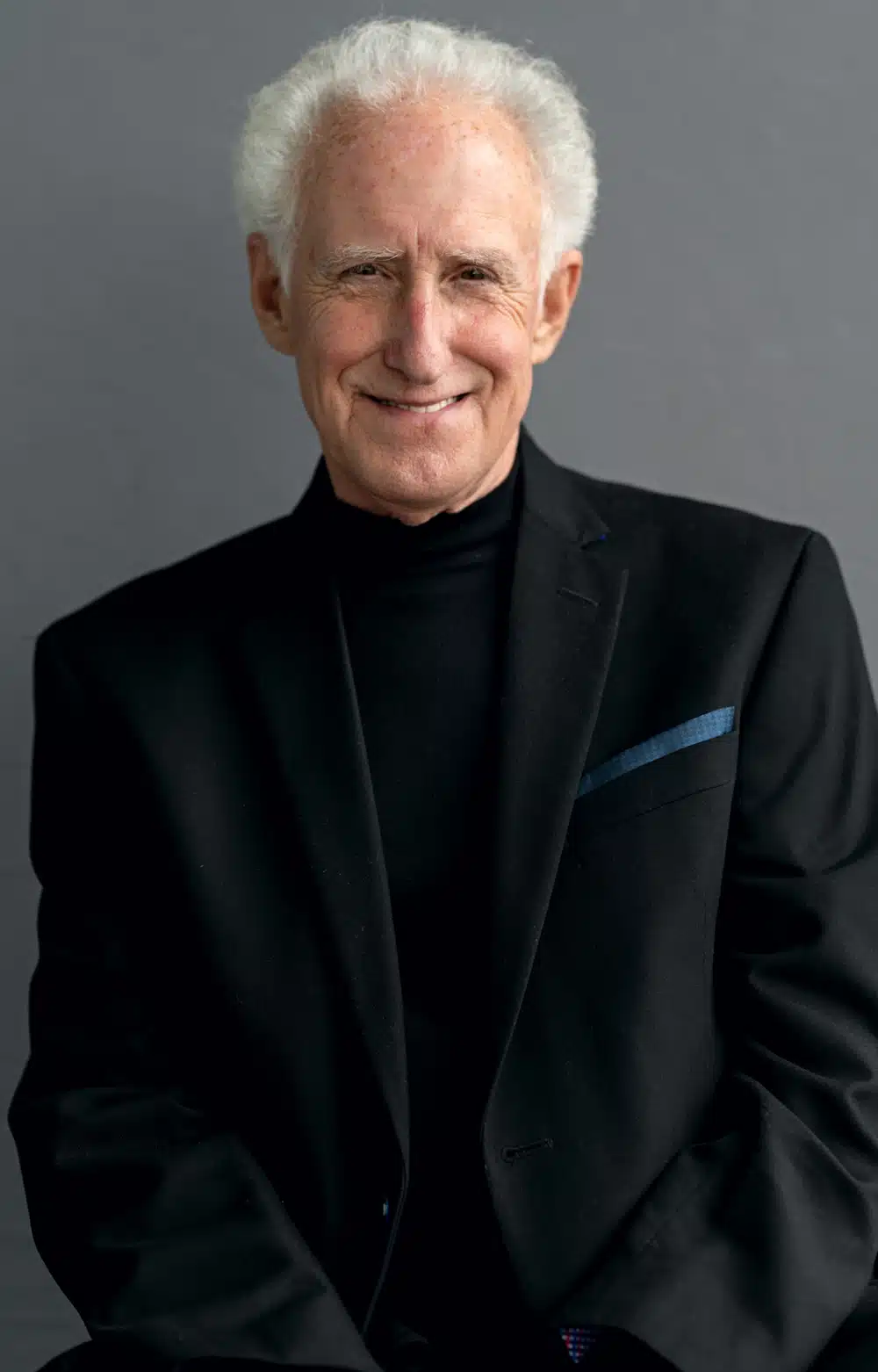

Con Fullam awakens in the darkness of 4 a.m. on Thursday, August 5, at his home in Windham, Maine. He is 73, and “it takes me a while now to get everything together,” he says. Later this afternoon, Pihcintu, the chorus of immigrant girls and young women he founded and directs, will sing live for only the second time since the pandemic made rehearsing, let alone performing, all but impossible. But first, he must get them to Portland.

The size of the chorus over the years has ranged from 20-something to as many as 44, with its members beginning as young as 8 and some remaining for a decade or more. Now there are 28 singers, and he hopes many of them will make it today. But he never knows for certain. It is summer, midweek; the older ones have jobs, and not all with managers who will let them go.

No matter that only a few weeks earlier Yo-Yo Ma had joined Pihcintu onstage in Bar Harbor for a Juneteenth celebration, or that the chorus had sung at the United Nations and the Kennedy Center and the National Cathedral, or that they had been featured on the Today show and Voice of America, or that they had performed at Governor Janet Mills’s inauguration. Or that today Univision will be filming them for a segment with Jorge Ramos, known as the Walter Cronkite of Latin America.

“I know no matter how chaotic it may seem at times, we will get it done,” Fullam says. “Four of our best singers can’t be here. You play the hand you’re dealt.”

First, Fullam drives 30 miles north to Lewiston to pick up Kaylee*, age 12, born in Texas to a Congolese mother. She wrote the melody for today’s lead song and will also perform its haunting solo. “She came to us when she was 8, and she could not be still for 30 seconds,” he says. “But singing was everything to her. She learned to concentrate while singing. Now she can be in a studio for hours until she gets the vocal exactly right.”

Kaylee climbs into the car at 7, still half asleep. From there, Fullam drives to Gray to pick up sisters Tania and Chrisianne from Rwanda, then to Westbrook to collect Janelle from Burkina-Faso and Yoselin from Honduras. He drives them all to Portland, where he picks up a van loaned by the Portland Housing Authority. Then he gathers up Brenda and Ceira from Sudan before finally reaching the Ocean Gateway, a glass-enclosed conference and event center overlooking Casco Bay, shortly before 10.

The seven girls walk in with Fullam, just behind the members of the Portland Symphony who will accompany them. Waiting inside is the acclaimed Kinan Azmeh Ensemble from New York, whose leader and namesake was himself once a Syrian refugee.

On this day the chorus’s performance will be live-streamed to the most unusual audience they have ever had: Little Amal, a nearly 12-foot-tall puppet portraying a 9-year-old Syrian girl who is walking alone from Turkey across Europe in search of her mother. But to call this creation merely a puppet is misleading. Little Amal is on a mission to represent the hundreds of thousands of migrant children who live in desperation around the world, not knowing what awaits them each day. They are children without a childhood.

To those who encounter Little Amal along her journey, she is a work of profound imagination, a dramatic depiction of a longing to find not only a mother, but also a place to belong. For the young singers of Pihcintu, there is no need to imagine this longing. More than 300 immigrant girls from 40-plus countries have belonged to the chorus since it began in 2005, and many arrived in Portland after surviving violence, famine, civil war. As one chorus member has described it, “You can’t see what I’ve been through by looking at me.”

Where for some people the phrases “migrant children” and “asylum seekers” may conjure up images of walls, or masses pressing against borders, Fullam sees faces and names. He knows the stories of everyone in the chorus—what happened to them before, and what struggles they may continue to face. “They have such courage and resilience,” he says. He recalls one girl who was carried by her aunt while escaping a fire fight because her mother was already carrying two of her younger siblings, all of them falling on the ground and crawling through blood. “When she came here and found the chorus, she was this tough, hard kid with every reason to be that,” he says. “And I saw her transform into this warm, loving, embracing woman she is today.”

As the chorus members are getting ready for their performance, Little Amal is 5,000 miles away, in the small Turkish city of Urla. She is nine days into “The Walk,” a five-month trek that will not finish until November, when she arrives in England. In between, Little Amal will visit more than 100 towns and cities; in each, she will be greeted with events, music, and crowds responding to a message of “Do not forget about us. Do not turn away.” The only live-music event in America is happening right here, today, on a small stage with fishing boats passing by just beyond the glass. Pihcintu singers dressed in pink T-shirts will sing to a packed room as a towering screen shows Little Amal listening in the dark Turkish night.

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

Over the next few hours, more chorus members arrive. The last one, Elizabeth, races in just before showtime—“I ran from work,” she says. After the first early run-through and sound check, I see a group of the girls outside on the deck, arms locked across their backs, kicking their legs high, laughing as they dance and sing. In a short while, the song they wrote for Little Amal will speak of sadness and longing, but now their voices are happy, and mingle with the cries of gulls wheeling by.

Alexandra Aron, founder of the Remote Theater Project in New York, who has been in Portland rehearsing and directing this segment of The Walk, could have chosen anywhere to connect with Little Amal. She came to Portland because it’s one of the most welcoming places for asylum seekers in the U.S., she says. “And when I learned about Pihcintu, it became clear that Portland was the ideal city. It was powerful to connect the girls with Amal.”

By 2 p.m. the chairs are filled, and people stand along the walls. Many wear red shirts that read “The Power of Welcome.” Little Amal, the sky dark around her, fills the screen.

In his career as a singer-songwriter, Fullam has written hundreds of songs and performed on some of the most legendary folk stages in the country. But the words to today’s opener, “Song for Amal,” were written by six Pihcintu members gathered in a room where he had placed a whiteboard and asked them to reach out to a child searching for her mother.

Kaylee holds the microphone, closes her eyes and begins to sing.

Feeling alone, without a home

how will you know where to go?

We know your pain

we have been there

we know your loneliness

and despair…

And the chorus joins in:

Amal, Amal, Amal can you hear?

Amal, Amal, Amal, have no fear

We will be there every step of the way

We will be with you every day

Until you find your way home.

On the screen, Little Amal’s hands reach up and cover her heart.

“One day when I tell my own children about this time, I will tell them that Pihcintu is the best thing I’ve ever done.” —Elsie, age 18, from Burundi

When Con Fullam tells the stories of how the girls in the chorus came to Maine, it’s as though he’s turning the pages of a family album. But when he’s asked how many of them know his story, it seems to be a question he hasn’t thought about before. “Very few,” he finally says. “Very, very few.”

Fullam grew up in rural Maine, a place so distant from his singers’ homelands they may as well have been on different planets. But this they shared, he says: “I know what it’s like to lose something that’s very dear to you and have no control over it.” When he was 5, his father, a beloved Colby College history professor, collapsed and died of a heart attack. He was only 48.

The family lived on a farm in Sidney, a small town outside Waterville. His father had been the Democratic nominee to challenge Senator Margaret Chase Smith, and the effort had left him exhausted physically and financially. “My father was a respected and revered member of the community, and the entire town just stood up and helped us get through,” Fullam says. “We were Catholics, and every Friday Bill the fish man gave us fish. If we needed anything repaired, somebody always showed up. If there was anything we needed, the community found a way to make sure we had it. We had no money. The bank actually forgave the mortgage on the farm. It had such an impact on me as a young kid to feel all this support and love around me. To this day, this is what dictates a lot of who I am and how I think about life. I have always looked for ways to pay that forward in any way I can.”

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

After his father’s death, his mother moved the family to Waterville, where she became a schoolteacher, and Fullam became a student for whom a C was a success. But he did have a gift for music. He had learned the ukulele from his father, and his mother, brother, and sister all played music. Music was how he found his way through the tragedy.

“I had a pretty hard time,” he says. “I was the only kid I knew that didn’t have a father. I was that kid, but being that kid isn’t what you wish to be. The ukulele gave me a way to define myself, [to show] that I was somebody. I remember standing up in front of my second grade class and playing ‘Sink the Bismarck,’ and it was a big moment for me.”

Fullam started his first band at age 14 and never looked back. He played at Maine ski resorts, then found his way in the early ’70s to New York’s folk and blues clubs. He began writing songs for major music publishing houses, churning out hundreds of tunes on demand, but in time he came back to Maine. There, he continued writing songs—including “The Maine Christmas Song,” which fills the state’s airwaves every December—as well as producing music and a children’s television show for PBS.

In the early 2000s, there was an influx of African immigrants in Lewiston and Portland, and what struck Fullam was how when they arrived they had no voice. “Literally,” he says. “They were strangers, and they did not speak the language. I thought if I formed a chorus, it could help them to learn English. And to feel part of a family. And to help them regain their sense of self and a sense of competence.”

On a cold, windy, rainy Saturday in November 2004, Fullam held an audition at a Portland school. “And four kids showed up,” he says. “I wondered if it was the weather or just a bad idea. Fortunately, teachers at the school told me to pursue it, and they introduced me to a nun at Sacred Heart, a school that had a lot of refugee children. I went there and asked if any kids liked to sing, and they all raised their hands. We went from four kids to 40. And word got out.”

The chorus needed a name. “Every name I came up with, like ‘Rainbow Chorus,’ either wasn’t very good or somebody else already had it,” he says. “So I went to the Portland Public Library and I got out the Passamaquoddy dictionary. I don’t know why I was driven to do that, but I did. And I opened it to a page and it said ‘Pihcintu: When we sing, our voices carry far.’ I thought, there it is. How could I have done better?”

Friends brought friends into the chorus. Sisters brought sisters. Fullam auditioned everyone, often in front of other chorus members so that there would be a challenge and a feeling of achievement. Nobody ever failed an audition. “I’ve never worried about the perfection of this chorus,” he says. “It’s not what the chorus is about. Even if you’re tone-challenged or pitch-challenged, the more you’re surrounded by kids who have pitch, the more you find it.”

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

They sang at local churches, schools, museums. Word spread. In the whitest state in the nation, here was this buoyant group of young people from war-torn countries singing of hope and peace, with a lean, white-haired guitar player leading them through the songs. “We started to gain some kind of notoriety,” he says. And then came the break that every artist hopes for.

On the morning of Christmas Eve 2015, the Today show aired six minutes of the chorus singing and its members talking about what it meant to them. “The girls knew it was a big deal, but also not really,” Fullam says. “They don’t watch the show because they are going to school. But they were home Christmas Eve. When they saw themselves on the Today show and when their parents saw them, they got the idea this was a momentous moment. When I watched, the hair stood up on the back of my neck. I knew something important was happening.”

Two years later, just before Christmas, the United Nations asked Pihcintu to write their own variation on “Silent Night” (Silent night, painful night / our mothers’ tears fall in fright) and come to New York to perform it. The video of the song was featured on all the U.N.’s platforms and was seen around the world. Then in December 2018, they became the only music group to ever sing before a working session of the U.N. General Assembly.

“That was quite a moment—just feeling the power of being invited into the inner chambers of the United Nations,” Fullam remembers. “They weren’t tourists; they were there to perform for the U.N. You walk into the General Assembly, and you see all the names of the countries. You could see the visible effect on [the girls’] faces. The U.N. means something special to a lot of them. A lot of them came from refugee camps where the U.N. had a powerful presence. This was very memorable for them.”

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

Despite the chorus’s portfolio of performances, despite the affirmation that indeed their voices carried far, one of the most meaningful concert reviews Fullam ever received happened in a church in a small town just outside Portland. “It was packed,” he says. “We had a really great show. Afterward, the pastor came up to me. She said there were two people in her congregation who came feeling truly anti-immigrant. She said we changed them that day.”

“When I’m singing to [Little Amal], I use that feeling that this is the journey I’ve been through, too.” —Brenda, age 21, grew up in a Kenyan refugee camp

Fullam says there are no stars in the chorus. Everyone’s voice joins in. But if there is a signature song in their repertoire, it is “Somewhere,” written by Fullam himself. A highlight of every concert, it brings members of the audience to tears. And when the singer is the smallest child onstage, a girl named Shy, whose voice that touches depths a child should not be capable of, the other chorus members simply say “Somewhere” is “Shy’s song.”

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

Shy is 13 now, and has been with the chorus since she was 10, when her family came from Namibia seeking asylum. It was Shy who sang “Somewhere” to the U.N. General Assembly, who sang “Somewhere” in Bar Harbor with Yo-Yo Ma’s cello a few feet away. One day I met a group of the singers at the Root Cellar, the Portland faith-based community center where they rehearse, and asked if they were jealous of Shy’s solos. “No—whoever is singing, it all comes out of one person,” replied Ruby, age 14.

Midway through the Little Amal concert, Shy closes her eyes and sings of a refugee’s plaintive hope that there will be a place in the world where she can find safety, solace, a future: Can you believe what I believe? / Can you, can you wish the same as me?

I look at the stage and I think of the stories I heard in that basement room at the Root Cellar, how these girls came to Maine and found what they call “our sisters” in Pihcintu. There was Prise, now 18, who spoke of being “haunted” by what she lived through for years in a Kenyan refugee camp. How she wakes with a start at the slightest noise, and how when she sings “Somewhere,” she cries. “It reminds me of when I was a child and thinking if only we can get out of here, we can be happy,” Prise told me.

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

I thought of Marciline, 18, who had reached Portland from Congo in the summer of 2019 after a journey of more than 13,000 miles, mostly on foot from South America through Central America, then through Mexico. It was months of danger that she does not talk about, and it ended with her on a green cot in the Portland Expo, along with hundreds of others who had made the same trek, hearing along the way there was a place called Portland, Maine, where they would find people who cared.

For Marciline, those people soon arrived—a couple who quickly grew to love her, and whom she would come to call “mother and father.” She sang in the shower, in the car, and on the way to school, where she wrestled with a new language, though she was already fluent in Portuguese, French, and Lingala. And they brought her to meet Fullam at a rehearsal, and he welcomed her by bringing over a member of the chorus who had also come from Congo, and now Marciline had found a new friend and soon was singing in a studio to make a music video with her new “sisters.”

Photo Credit : Séan Alonzo Harris

The concert ends when Little Amal bows and the screen goes dark. Her walk will continue for thousands of miles. Fullam has an interview with Univision, and then he has the return drive to make, with drop-offs in Portland, Westbrook, Gray, Lewiston. He does not reach his own home until after 8. “A good day,” he says, “but a long day for old people.”

It has also been a bittersweet day. He has known Fatimah ever since she came from Iraq when she was 8 and became one of the leaders of the chorus. Now a high school senior, she has just told him this will be her final appearance. That she now feels that singing is no longer compatible with her religion.

There has always been a fragile nature to the chorus. Uprooted families face hurdles, and sometimes they must move. A number of Fullam’s most experienced singers are now heading to college. Until recently, because of Covid, he was unable to bring new members in. But four more have just joined, some of whom arrived in the 2019 summer surge with Marciline. He calls it “the need to replenish.”

He feels his age. “The 12-hour bus trips to Washington, D.C., take their toll,” he says. “I’m very aware I need a succession plan.” He hopes to involve a refugee from Angola who plays the guitar and comes to rehearsals, and whose daughter has just joined the chorus. Fullam knows he has to do more to find additional grants to keep Pihcintu on solid ground. He hopes they will find their angel, someone who sees their videos, listens to their CD, and wants to ensure they will always be heard, even as the names and faces of the singers change.

Soon after the Little Amal concert, the Afghan government falls, and there is no doubt that Portland will reach out to help new refugees. Among them will be girls and young women who will feel lost, without a voice to express what they feel, bewildered by customs and a language that at first it seems they will never grasp. Maybe they will come with a social worker, or someone they meet in school. But they will find Pihcintu. They always do.

“And when they walk in, we will welcome them,” Fullam says. “I consider myself immensely fortunate. I get to see these girls grow up and flourish. Some flounder, but they always find a way to end up on their feet. I get an emotional lift, being a little part of their lives.”

To learn more about Pihcintu and to watch the group’s videos or buy their CDs, go to pihcintu.org or visit their Facebook page.