Yankee’s Yankee

Editor Mel Allen celebrates the healing power of storytelling — something no one does better than “Yankee’s Yankee,” Jud Hale.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanIn 2020, an unprecedented American public health crisis profoundly changed the way we live, prompting editor Mel Allen to begin posting regular “Letter From Dublin” dispatches from Yankee‘s home in southwestern New Hampshire. This installment first appeared on June 18.

When your world narrows — as it did for me in late March, when many of us retreated to our homes — then narrows even more with each passing week, you think about people you once saw nearly every day who now might as well live in another country. And in a sense they do. Which is why yesterday I phoned Jud Hale, Yankee’s longtime former editor, under whose watch the magazine became an icon of New England. When I asked how he was, he said he was OK. “I’m not supposed to,” he said, “but I’ve been sneaking out to go to the post office.”

Jud lives in a retirement community only two miles away with his wife, Sally, in a pretty cottage set amid woods and by a river. He is stepping gingerly into his later 80s now, and the past few years have forced him to shed some of the most important fixtures in his life: the island home on Lake Winnipesaukee, where his three sons and later his grandchildren felt a summer day had no end; his home in Dublin, where he wrote in a tower room; his “House for Sale” column, which he wrote as “The Moseyer” for decades; his decades-long succession of golden retrievers, various mutts, and finally Murphy, a long-haired dachshund, whom Jud carried with him on journeys until Murphy, grown deaf and blind, could not hang on any longer.

Before the pandemic sent us all home, Jud still came to the office nearly every day. In winter, the parking lot can get dicey, no matter how urgently it is plowed and salted. For several years we have urged Jud to park in a reserved spot by the front door. The more we asked, the more he dug in and refused, deliberately, it seemed, choosing to park as far away as possible. He once spent three years as a tank commander in Germany, and whatever residue remained from those days roared back at our efforts to tell him that we worried.

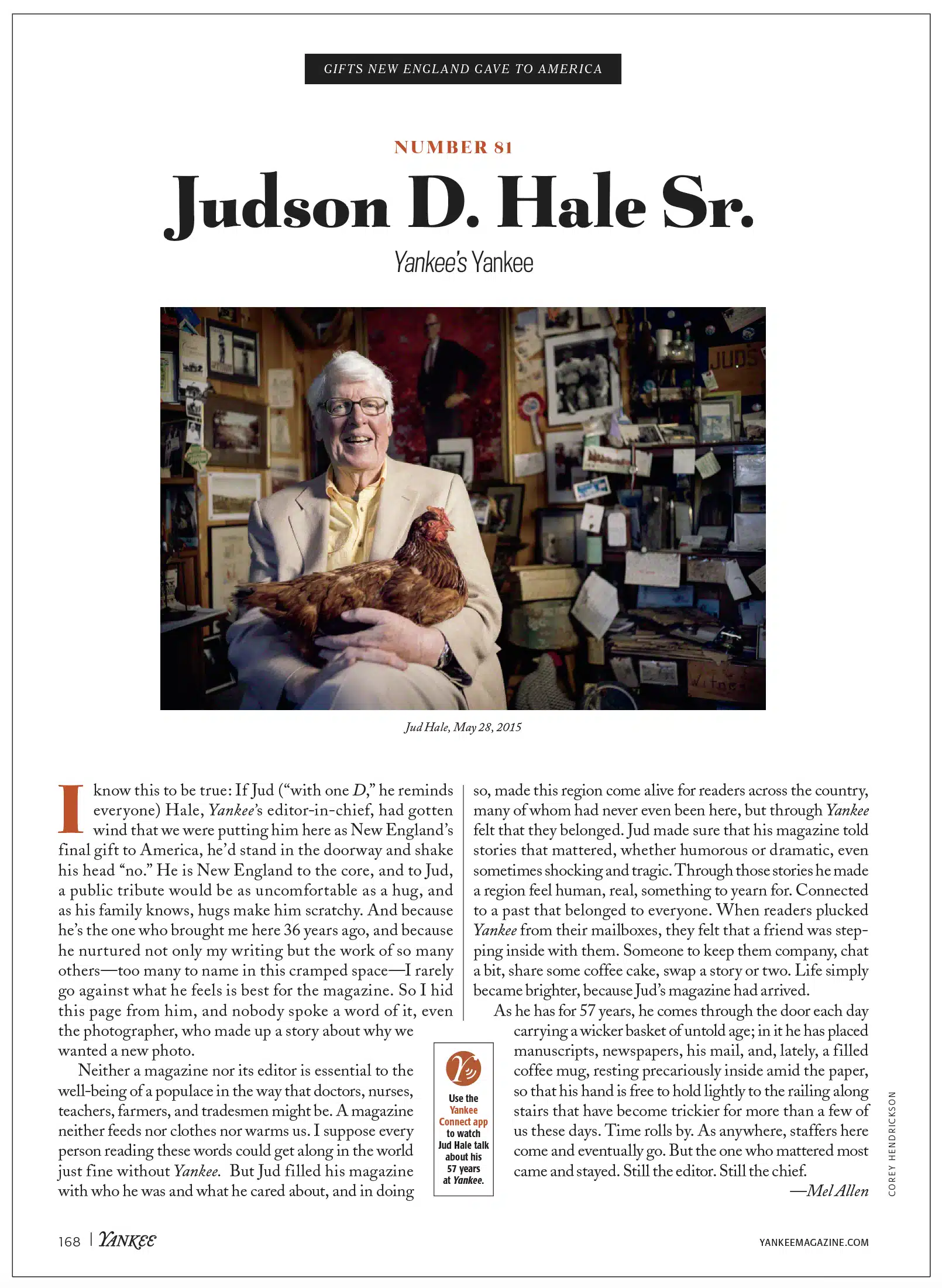

He’d arrive around 10:30, give or take a half hour, chat for a few minutes with Linda, our receptionist who has been with Yankee for over 50 years, before climbing the stairs to his second-floor office, clutching his wicker basket that held a Boston Globe, a mug of coffee, and pieces of mail. We could hear him walking down the hall as he called out to each person in their office: “Hi, Janice… hi, Tim… hi, Ian… hi, Heather… hi, Joe…” If the New England Patriots had played the day before, he would linger outside the office of Joe Bills, a former sportswriter, and deconstruct the game. Which was notable, since Jud cared so much about the team he could rarely bring himself to watch. He’d then sit at his desk, drink the coffee, read the newspaper, open his mail, and make a few phone calls, his voice booming down the hall.

After an hour or two, he’d walk back down the hall, basket empty, down the stairs and out the door. To an outside observer, he had achieved little. To those of us in the office, he had shown us how what we do stuck to him like a burr, how the meaning of this work remained, and he just wanted to be part of us, even on days of ice when we looked out the windows as he made his way across the pavement.

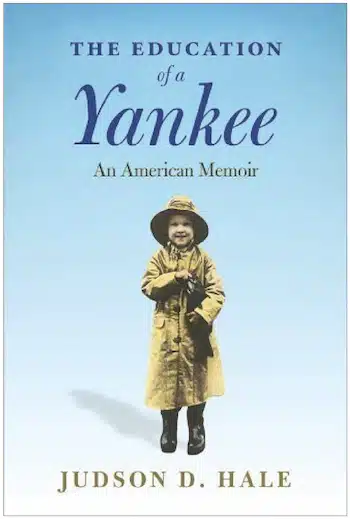

He attended our Thursday editorial meetings, and we began each one with what we called “Jud’s Three,” during which he would read or talk for three minutes about some quirky or historical New England tradition or tale. He has been with Yankee since 1958, when he joined his Uncle Robb’s magazine as a do-everything assistant editor, and he had a lifetime of anecdotes to pass down. He was — and remains — a storyteller. He wrote three books, and his best, The Education of a Yankee, makes clear where the stories began.

Though born to Boston wealth, his parents moved the family to the wilderness village of Vanceboro, Maine, on the edge of the Canadian border, where they lived on 12,000 acres of both farm- and timberland. His father employed every logger for miles around, and his mother started a Waldorf school based on the teachings of Rudolph Steiner. “When I dream, I always dream of Vanceboro,” Jud once said to an interviewer.

He always told his writers that storytelling mattered above all else, that we had to make readers feel. Make them laugh, or cry, or be amazed, but they could never be bored, and if they felt emotion they would want more. You wanted to write for Jud the best story you had in you, because he believed you would.

I would not be writing this letter if it were not for Jud. When I met him in 1977, he had taken over the reins of both Yankee and The Old Farmer’s Almanac a decade earlier. John Pierce, the new managing editor of Yankee, brought me to Jud’s office after softening him up a bit by saying that he had read stories I had been writing for Maine newspapers, and that Jud should get to know me.

Photo Credit : Ian Aldrich

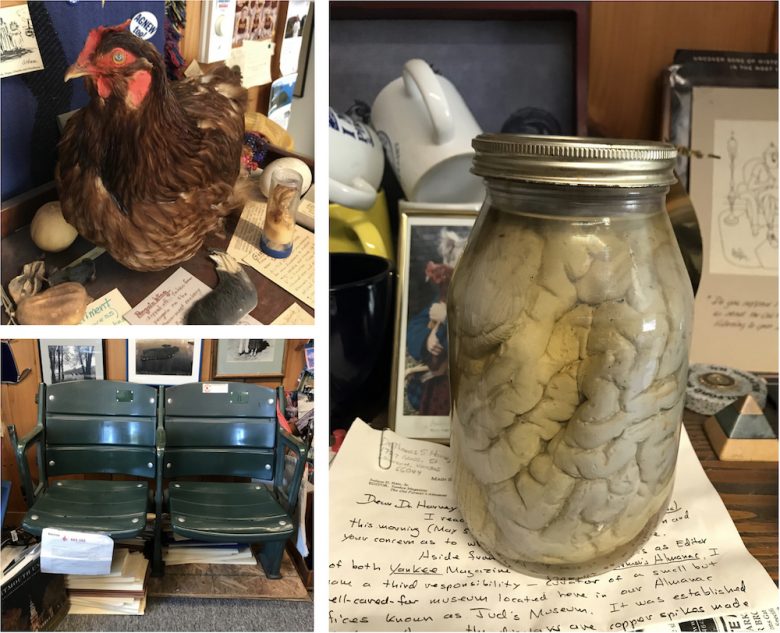

Few people enter Jud’s office without getting a tour of what he calls “Jud’s Museum,” and so before I talked story ideas, I was brought into a small world that is best described as something akin to one of those strange roadside collectible places, except this curator was a tall, blond-haired man, educated at Choate and Dartmouth, who took delight in setting a banana peel on a shelf to see how long it would take before it dissolved.

He showed me a safety pin from the first flight over the North Pole, and a piece of cloth from Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis, pebbles from Red Square, a photo of Red Sox legend Ted Williams, and a letter rescued from the Titanic. Over the years, I never learned of anything that was removed from the museum, just more “treasures” he wanted us to know about: seats from Fenway Park that were removed during renovations, and a humble jar labeled “Einstein’s Brain.”

When Jud read that the doctor who had performed Einstein’s autopsy had kept the brain to study, he wrote asking if he could have it in his museum. He added he would respect it and care for it. The doctor wrote back. He had promised Einstein’s family it would not go on display. Jud wrote once more: He would keep it out of sight in a drawer. The doctor never answered. Undaunted, Jud created “what his brain would have looked like,” as he’d tell everyone who looked at the jar in wonder. In time it became hard to know whether the museum reflected Jud’s idiosyncratic tendencies, or whether in his efforts to keep himself entertained by all that surrounded him, he became its most original artifact of all.

Photo Credit : Ian Aldrich

That day when I met Jud I came with a list of 28 story ideas. He said he wanted 25. He and John Pierce assigned me a story each month, $600 apiece. To make my life easier, they gave me a contract so a check would arrive early each month. To a freelancer, this was like finding a hidden door. A year later, my dad, who had retired to Florida, discovered that the back pain he had complained about was lung cancer. The more time I spent seeing my dad, the more I fell behind to keep up with the monthly stories. John and Jud then told me they had retroactively changed my story fee to $800, so I was caught up. There are gestures one does not forget.

A few months before my father died, Jud asked me to join Yankee full-time. I told my father as he lay on his bed, his eyes glazed by opioid painkillers. The lessons of the Depression had burned into him, and he had long fretted that my freelance life was a precarious way to live.

“I’m going to Yankee full-time,” I told him.

“Benefits?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. He smiled, one of the last I can remember, said, “Good,” and then he closed his eyes and slept.

It is easy to look back on my years with Jud and to play the game of where I would be if he had not wanted so many of my stories; if he had lost patience with a young writer who could not fulfill the deal he made. Sometimes I give a talk to some group that wants to know about Yankee. I always begin by saying, “This is a story I heard from Jud Hale.”

He and his wife, Sally, were somewhere around Tamworth, New Hampshire. Sally had an upset stomach. At a general store Jud stopped to get her some Tums. As he entered the store he noticed an old fellow sitting quietly in a chair next to the door. Jud walked up to the counter and asked the proprietor for Tums.

“I’d like the cherry flavor, please,” Jud said.

“We don’t have the cherry-flavored Tums,” the man replied.

“Well, do you have the orange flavor?”

“No, we don’t,” said the man.

“Well, then,” Jud said, a little exasperated, “I’ll just take the plain Tums.”

After paying for it, he was walking out the door when the old fellow in the chair looked up at him as he was passing by and said…

“Looks like you’re gonna have to rough it.”

The audience always laughs, and I bask in Jud’s light for a while. We are all roughing it now, and we don’t know when life will smooth out. But it will, and when it does, I’m going to ask Jud to make it five, not three minutes, and to make us laugh, maybe cry, to remember the power of a good story to pick us up no matter how often we fall.