Sitting Around With Thomas Moser

New England’s foremost furniture craftsman hangs his hat in the house that he and his wife built on Maine’s Dingley Island.

A bank of windows in the Mosers’ master bedroom provides a million-dollar view of Sheep Island.

Photo Credit : Mark FlemingThomas Moser at home can sit anywhere he likes, in multiple chairs of his own design. But on this particular Maine morning in mid-July, as the sun burns through a haze surrounding Dingley Island, 12 miles south of Brunswick, the 83-year-old master furniture craftsman is propped in a leather recliner that is most definitely not of his own making.

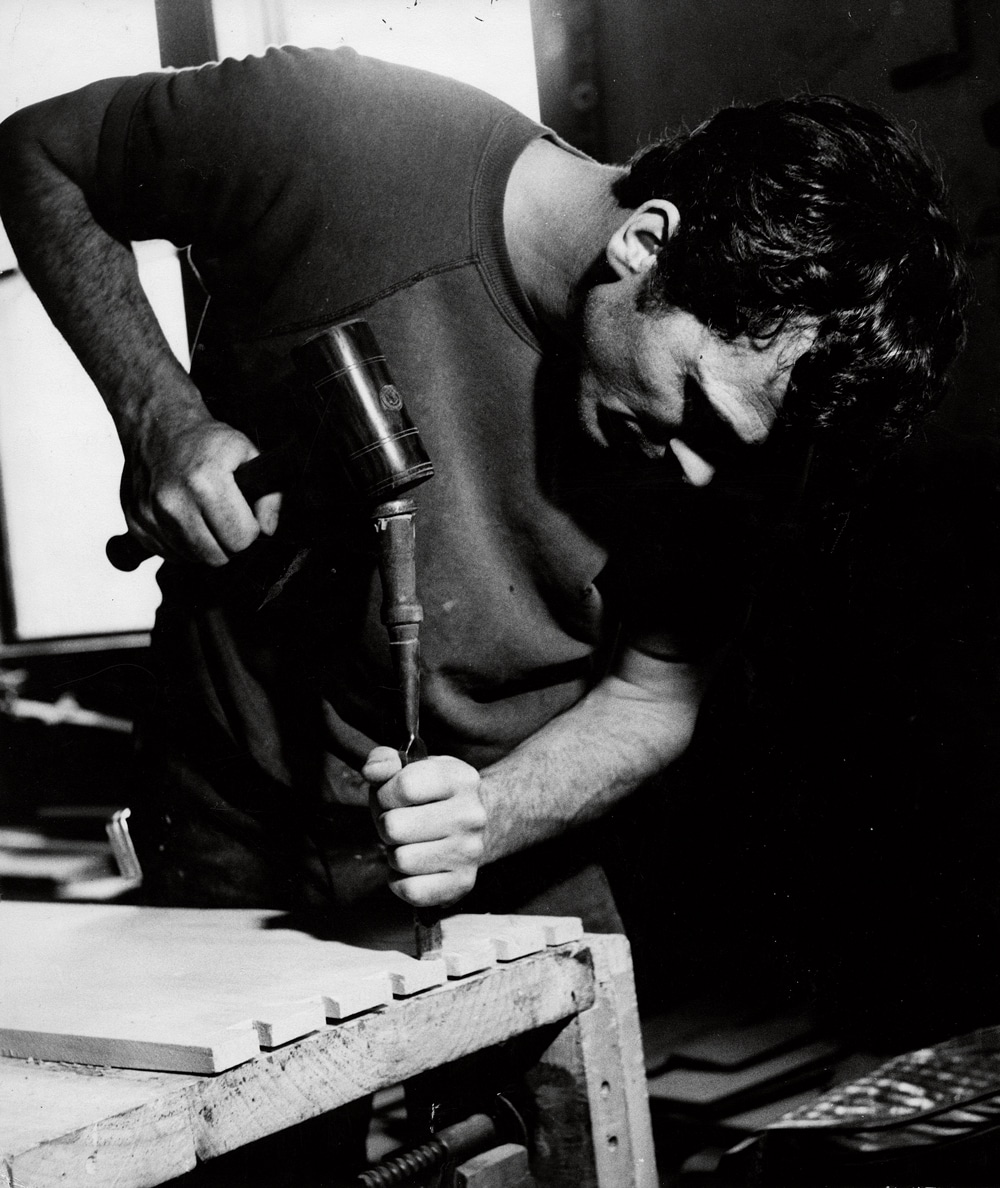

“My back!” he barks, with barely contained impatience. The founder of Thos. Moser insists that 40-odd years of hovering over a workbench—tinkering with prototypes, tweaking this element or that to craft a spare beauty like the swooping Continuous Arm Chair—is not the culprit, as one might expect. Rather, the lanky craftsman accuses a ladder. Specifically, the one he’s co-opted for the past few days while freshening the white trim of the 3,200-square-foot Cape that he and his wife, Mary, built in 1993.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

The house sits on the land as if washed up from the sea, with water on three sides and a straight-on view of Sheep Island. “We’re in the northern reaches of Casco Bay,” Moser says. “If you look out straight, that’s open ocean. It’ll probably take you to South America.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

But he’s here, of course. In Maine. “We’ve been citizens for 50 years,” he says, then pauses. “Fifty years since we took citizenship,” he repeats emphatically, this transplant from Illinois. In the title of an 86-page biographical sketch he wrote last year, Moser asks: How Did I Get Here? And to me, he asks, “How did somebody who never got much beyond halfway in high school become a college professor? How does a college professor become a wood craftsman? And then, how does that become a business? These are improbables!”

Part Renaissance man, part coxswain, with a dash of Hemingway, Moser sprinkles his sentences with exclamation points and poses questions with professorial directness. And yet, evidence of improbability is everywhere. In 1972, Moser took a sabbatical from Bates College, in Lewiston, where he taught speech and communications and was the debate coach (“They called me the mouth without a cause—I could argue either side”). He opened a workshop with little more than a table saw, a belt sander, some hand tools, and Mary’s staunch support (childhood sweethearts, they’ve been married since 1957). “We did everything back then,” Mary recalls, from building reproduction Shaker furniture to restoring old clocks, landscaping, and renovating and selling historic houses (about 29 of them).

Photo Credit : courtesy of Thomas Moser

“I like to say I learned from dead people,” Moser says. He even wrote a book, How to Build Shaker Furniture, as a tribute to his earliest influences. But when Eldress Gertrude, one of the last Shakers at Maine’s Sabbathday Lake, remarked of the book, “Imitation is the highest form of flattery,” the couple decided it was time to start creating furniture that was recognizably their own.

The design thread that began with Shaker values—understanding and respecting materials and utility—now took on other influences, from Frank Lloyd Wright to George Nakashima, whom Moser credits as being one of the most important figures in furniture (a Nakashima chair graces their upstairs hallway). “The first five years, we didn’t know what we were doing,” says Mary. “Then we got serious.”

Thos. Moser grew from 12 employees in 1978 to its current staff of 135. The company’s lean, elegant furniture has been snapped up by university libraries and statehouses; it’s been admired and sat in by presidents and popes. More improbables.

And, there is this house.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

“We were always looking for a place on the ocean,” Moser says. “When we could afford $125,000, everything was $300,000. When we could pay $300,000, everything was more.” In August 1988, he and Mary bought this Harpswell Peninsula property: a 14-acre parcel on a spit of land, with a half mile of frontage and a view of Cundy’s Harbor, one of the “last genuine fishing villages” in the area, says Moser. At the time there was nothing here but an unlivable cottage, built in 1924, and an ice pond (the Mosers’ quarter-mile driveway is flanked by freshwater on the right; ocean to the left).

The couple sold everything, including their New Gloucester home and boat, and “went into deep hock,” Moser says. They renovated the cottage and lived in it while building the barn (a combination apartment/boathouse/garage/workshop). Then they occupied the barn while spending three years raising the house. In summer 2016, they made their final mortgage payment. “When you’re 80, you shouldn’t be mortgaged,” Moser says, with the brusque certitude of the almost-Maine-born.

Moser describes the house that he and Mary built as a “big Cape Cod,” with three-inch-to-the-weather clapboards and white cedar on the gable ends, to keep the look traditional. The sunroom, overlooking the water, came later, as did the hot tub (“You can run around naked, but you’ve got to watch out for the lobstermen,” says Moser).

“How did we know where to site the house? We put up scaffolding, sat back, and said, ‘This is what we want to look at when we wake up in the morning,’” Moser says. “This house was built from the inside out, not the outside in, the way it’s usually done.” Which, co-incidentally, is how he designs a chair. Moser has written, “It’s still common for me to design and build a piece with little notion of its measurements.” He confesses that his drawings for the house consist of scraps of paper, jumbled together somewhere in a drawer.

Behind the house’s traditional-looking exterior, the Moser domain is a pageantry of woodwork. He and Mary did much of the labor, including building all the doors, insulating, and hanging drywall. They made custom trim and baseboards in the workshop; they designed the kitchen cabinets. “Every room reflects 100 percent of who we are,” says Mary. “A little schizophrenic, and it’s all here.”

“It wasn’t built or designed to please anyone but us,” Moser agrees, citing two bedrooms and five baths.

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

Ceilings rise to 8½ feet except in the open entryway, which soars to the second floor, with a starkly elegant railing up above. Sculpted busts of the couple’s four sons—David, Aaron, Matt, and Andrew, who’ve all been involved with the business—congregate on the first floor, more Moser handiwork.

The library/study is encased in walnut, with a ceiling “right out of Kyoto,” Moser says. There’s a secret room, too, which I scramble to find, although Mary reassures me that “everyone who comes into the house knows where it is anyway.”

No matter. Wood reigns supreme here—the same eye that envisioned Thos. Moser furniture is evident everywhere. There’s mostly cherry trim downstairs and walnut trim upstairs, but there are some tantalizing deviations, too. The floors on the ground level are made of teak from Myanmar, dredged up from under 60 feet of water. Upstairs, the bedroom’s panoramic view is framed by tidewater cypress taken from an 1802 cotton warehouse in New Orleans.

With this preponderance of wood, the dividing line between home and furnishings is often negligible. Sometimes, as in the salmon-hued dining room, the furniture dominates. Which leads me to ask Mary: When you’ve had a lifetime of Moser designs, how do you decide what ends up in your house?

“It’s what was available,” Mary says with a smile, as we admire a massive walnut dining table that seats 14. “Most of what we have are prototypes. This was an extra college library table, and I was lucky enough to get it. It’s been here since we built the house.” The living room couch is a prototype from an art deco line that didn’t work out. In fact, all of the living room furniture is Moser.

“Sit in that!” yells Moser from the kitchen, and I sink into his Rockport Chair, placed off to one side in the walnut-enveloped living room. It fits like a glove. But in fact, sitting in a Moser chair in a Moser room feels a little like sitting in a hall of mirrors. The wood-paneled rooms are simply a further extension of the Moser principle.

If he had it to do over, Moser says, he’d build a glass house. And yet, when he stops to think about what he loves about this place, the words spill out quickly, without reservation. “From the bedroom, it’s a 130-degree uninterrupted view. The Milky Way is directly overhead. Not an electric light to be seen—we might as well be in the 12th century.”

Mary nods. “It’s a thrill to go upstairs.”

Photo Credit : Mark Fleming

They glance at each other, some sort of unspoken language that communicates the years and the accomplishments.

“When I wake up, I just pick up a pillow and prop it against the headboard,” Moser says, his blue eyes drilling a hole in the horizon. “And I thank God and providence that I am where I am.”

Annie Graves

A New Hampshire native, Annie has been a writer and editor for over 25 years, while also composing music and writing young adult novels.

More by Annie Graves