Gardens

Roses | Advice from Suzy Verrier

Yankee Classic from June 1992 “I hate to tell you,” Suzy Verrier said, pausing sympathetically, “but your roses are wimps.” “Come again?” I wasn’t sure I had heard her correctly. “Wimps,” she repeated. “They’re wimpy commercial roses that are packaged and sold like canned tuna.” Another pause. “They’re fine, I suppose, if you like canned […]

Yankee Classic from June 1992

“I hate to tell you,” Suzy Verrier said, pausing sympathetically, “but your roses are wimps.”

“Come again?” I wasn’t sure I had heard her correctly.

“Wimps,” she repeated. “They’re wimpy commercial roses that are packaged and sold like canned tuna.” Another pause. “They’re fine, I suppose, if you like canned tuna.”

This was discouraging news, I must admit. I’d sunk several hundred dollars into young rose stock, and my first summer as a rose gardener was drawing to a close. Half my roses looked absolutely splendid, pink and healthy. The other half? Spindly, bug-eaten, downright dead in spots. Canned tuna, eh?

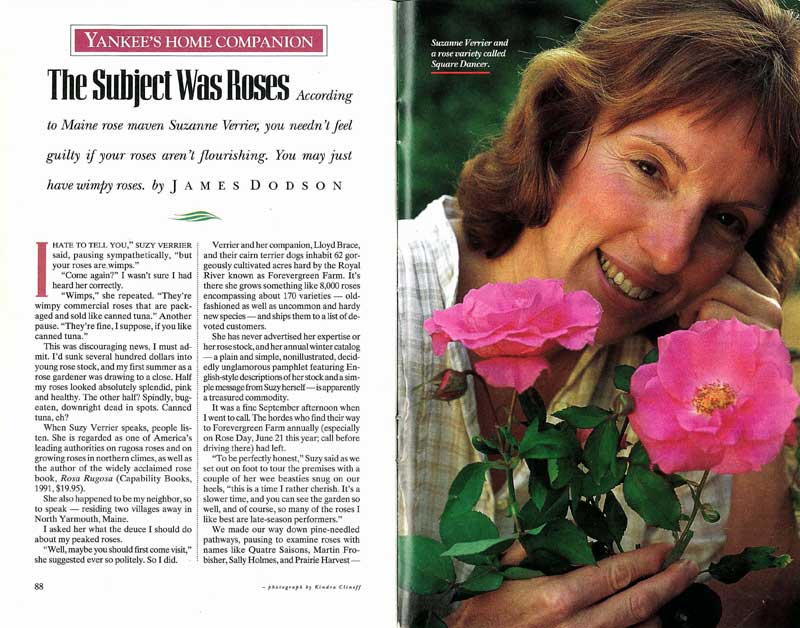

When Suzy Verrier speaks, people listen. She is regarded as one of America’s leading authorities on rugosa roses and on growing roses in northern climes, as well as the author of the widely acclaimed rose book, Rosa Rugosa (Capability Books, 1991, $19.95).

She also happened to be my neighbor, so to speak – residing two villages away in North Yarmouth, Maine.

I asked her what the deuce I should do about my peaked roses.

“Well, maybe you should first come visit,” she suggested ever so politely. So I did.

Verrier and her companion, Lloyd Brace, and their cairn terrier dogs inhabit 62 gorgeously cultivated acres hard by the Royal River known as Forevergreen Farm. It’s there she grows something like 8,000 roses encompassing about 170 varieties — old-fashioned as well as uncommon and hardy new species — and ships them to a list of devoted customers.

She has never advertised her expertise or her rose stock, and her annual winter catalog — a plain and simple, nonillustrated, decidedly unglamorous pamphlet featuring English-style descriptions of her stock and a simple message from Suzy herself — is apparently a treasured commodity.

It was a fine September afternoon when I went to call. The hordes who find their way to Forevergreen Farm annually (especially on Rose Day, June 21 this year; call before driving there) had left.

“To be perfectly honest,” Suzy said as we set out on foot to tour the premises with a couple of her wee beasties snug on our heels, “this is a time I rather cherish. It’s a slower time, and you can see the garden so well, and of course, so many of the roses I like best are late-season performers.”

We made our way down pine-needled pathways, pausing to examine roses with names like Quatre Saisons, Martin Frobisher, Sally Holmes, and Prairie Harvest — all gloriously blooming. Suzy kept up a strolling commentary on American rose culture, trends in cultivation, plant characteristics, growing altitudes, and her own distinctive opinions about a variety of rose commandments. Some cultivated highlights:

“American gardeners have an inferiority complex when it comes to growing roses. They are conditioned by the big greenhouses with their glossy catalogs to buy roses that will supposedly bloom easily, perfectly, and constantly. They want perfection. If they don’t get it, there is something wrong with that rose. Half the roses the big houses sell are called hardy — but they’re really hardy only to places like Maryland or Virginia. There are so many microclimates in America that you really have to pick and choose carefully, but also experiment year to year, move things around. I think a great deal of misinformation is dispersed through those big outfits.”

“The most common misconception about planting roses is that the graft should be just above the ground level. In fact, in a climate like ours, it should be at least three inches below the surface! That way, if your kids run over it with a bicycle or the severity of winter damage is great, the plant will undoubtedly come back. We’ve also been taught to prune roses in the fall. That’s wrong, too. The longer canes help protect the plant, and by cutting them back for winter, you’re only assuring more winterkill.”

“We don’t spray at Forevergreen Farm. People are so hyper about a few little spots. Sure there are periods when Japanese beetles or aphids are pretty active, but in my experience, by the time you can do something about them, the damage is done. Besides, the pests seldom last long.”

“We don’t use a commercial rose food. We use manure, a vitamin-hormone supplement, and a seaweed and fish emulsion called Sea Mix, which we apply rather infrequently, certainly not every two weeks as some of the commercial mixes suggest. Hit them with Sea Mix and some manure in midsummer. I find one common sin of rose growers is that they overfertilize and overwater. New roses should be watered heavily their first year, but after that, if the root system is good, you should water them frequently only through midsummer.”

“Mulch! Now here’s a problem area. I regret to say that the traditional bark mulch you find at most gardening centers is in fact terrible for gardens. It takes the life right out of the ground. It is insufficiently decomposed and still has living material in it that actually sucks the nitrogen right out of your plants! It’s hard to convince people that this is true. But it’s becoming my personal mission! You need to find a dealer who offers a decayed compost of old hay, food scraps, anything organic that’s decently decomposed. You want a mulch that is going to contribute to your rose garden, not starve it to death.”

We concluded our tour with a cool drink by a reflecting pool. We talked about my particular rose problems, and she made a few specific suggestions. “I’m sorry I called your roses wimps,” she said in the end. “What I meant to say was, there’s so much more you can do – roses really aren’t as difficult to manage as we’ve been led to believe. The good news is, there’s a world of possibilities out there.”

On that encouraging note, I lifted my glass to Suzy Verrier — and a rosier future.