From Away

Maine had been her haven since childhood. Then a virus arrived, and with it a fear of outsiders. Award-winning journalist Rachel Slade recounts her family’s Covid quarantine experience in this thought-provoking essay.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanOn March 17, 2020, my husband and I fled our Boston apartment for Maine. I had no idea what the future held—at that point, no one did—but with the number of Covid-19 cases doubling every day in Massachusetts and New York, Sean and I activated our version of an escape plan.

Before the pandemic, we’d joked that if civilization ever teetered toward collapse, we’d abscond to his house in the Maine woods, get a few goats and chickens, and live off chèvre omelets. I secretly lived in that punchline, even though the closest either of us had come to animal husbandry was petting the sheep at the county fair.

Maine had always been my survival plan, though I wasn’t a Mainer, and neither was Sean. He was from suburban New York. I was raised in the suburbs of Philadelphia and had spent summers in Maine since I was a kid. My parents had honeymooned on Lake Sebago in 1967 and in spite of a miserably hot, mosquito-infested week, they kept coming back each summer, renting houses on the coast as the family grew from two to five, plus dogs, in-laws, and eventually, granddaughters.

In the city, my parents worked days, nights, and weekends to save up for their own place someday, leaving us kids to run feral in suburbia. But for one magical Maine week each year, we became a family.

At the end of August, my dad would methodically pack the Oldsmobile station wagon, my mom would empty the fridge into a portable cooler, and we’d drive 12 hours up the interstate to the Maine coast. Sometime after midnight, the sound of high weeds whacking the underside of the car would signal that our vacation had officially begun. After loading in and downing a beer, my dad would call in the dogs, switch off the lights, and climb the stairs to Mom, already unwinding with her chardonnay. I’d lie in the dark next to an open window, inhaling the cool sea air and listening to the awesome silence, which was sometimes punctuated by the bark of a harbor seal. At dawn, I’d wake and make my way to the water to watch the rising sun sparkle off the bay, captivated by the cacophony of seabirds feasting on a low-tide buffet.

Photo Credit : Hokyoung Kim

Maine put a spell on us. In Philadelphia, we were five people living in the same house. No one had any time; we merely tolerated each other. My brother Dan, for example, six years younger, was an inconvenience and annoyance, a scrawny kid at the dinner table carefully extracting curds of ricotta from his lasagna and wiping them on the side of his plate.

But in Maine, my mom cooked elaborate meals and my dad planned family hikes with his maps and trail guides. Cut off from friends and other distractions, my brother and I discovered that we had things in common. I began to appreciate that scrawny kid with the weird eating habits.

By the time my parents bought land on an island halfway up the coast to build a life quite separate from their suburban existence, Dan and I were in our twenties. The new house had more light and less baggage, which gave us room to start fresh as quasi-adults.

At the island house, we developed rituals that brought us closer together, like the twilight pilgrimages to the granite boulder at the water’s edge, where the two of us, cocooned in throws from the back of the living room sofa, watched for meteors while spouting half-baked philosophical nonsense and the occasional deep thought. When the mosquitoes found us, which they always did, we’d stumble back to the house, tripping over roots and rocks, clinging to our blankets like armor.

Those August nights with Dan were sacred. We might be small and inconsequential on a rock at the edge of the ocean under a vast universe of stars, but we were also siblings, which turned out to be another kind of marvel. Over the decades—between schools, jobs, cities, and relationships—we always found time to lie under the Maine night sky.

Every place I’ve ever lived—New York, Philadelphia, Boston—seemed like a temporary but necessary stop along the way to a life in Maine. And when I discovered that Sean had a place in Maine, I knew I’d found my man. The fact that he’d chosen to settle there guaranteed that we shared something fundamental, almost like a religion.

He’d bought his house in the ’90s, a decade before we met. His house was inland, about five miles from the sea. Its wide deck overlooked a small, murky pond where a neglected dock, occupied mostly by ducks and snapping turtles, struggled to stay afloat. Inside, the home was a manifestation of the erudite madman I loved. Sean had packed every closet and cabinet with his books and records and magazines. On the second floor, the sun had bleached the Renys comforters he’d thrown over the trappings of his life before we’d met: old recording equipment, microphones, musical instruments. The house was also a repository of family ephemera, including boxes of stuff dumped out of relatives’ desk drawers in haste after they died.

Marrying Sean meant respecting this monumental accretion of history. I worked quietly to nibble out a space for myself, and after 15 years I’d finally established a solid home in Maine with my husband. By early 2020, I had my own desk and chair, a drawer in a bureau, and a sliver of carpet on the second floor where I could lay out a yoga mat. As a test run, we spent the whole month of January there. Our life together in Maine began to feel within reach.

Just two months later, that theory would be put to the test. When the country was shutting down, I gathered provisions in our Boston living room, things my inner prepper thought we’d need. There was the 25-pound bag of flour. There was the industrial-size bottle of ibuprofen. There was the extra-large bag of cat food (for the cats, I should add). We packed up the Subaru and headed north—this time, I thought, for the long haul.

And I sincerely wondered whether I’d ever come back.

— — —

On the Sunday morning after we arrived, Sean and I did a big, panicky Hannaford shop and, worried about bringing an invisible enemy into the house, bathed our provisions in soapy water on the porch. I read somewhere that the pandemic would reveal which partner was a better prepper, and I was sure it would be me. Sean bought the food. I deep-cleaned and sterilized everything. I unearthed a novelty bottle of hand sanitizer labeled “I *heart* my penis” in the back of a drawer while emptying out Sean’s father’s desk, another Covid-eroded boundary. Sean stashed it in the cup holder next to the driver’s seat.

Then we settled into quarantine life.

Maine felt like a natural place to wait out a pandemic. Mainers were survivors, I reasoned. They kept a low profile and minded their own business and didn’t go looking for trouble. My faith in Maine was based on a mythology I’d pieced together from locals I knew.

On the island, my parents’ next-door neighbor, Walt [*name has been changed for this issue], for one, was a lobsterman and a descendant of God-knows-how-many generations of islanders. Walt plowed our driveway in the winter and helped my dad get his small sailboat to the mooring in the summer. Sometimes, Walt would walk the half mile down the driveway from his house to ours, stepping onto the front porch in a tangle of my parents’ dogs, who had followed him most of the way. Maybe his stopping by was just being neighborly. Or maybe he was curious about us folks from away.

It was through Walt’s manner and attitude that I gleaned basic Maine doctrine: Never give more information than required (standard fisherman’s credo), don’t bother your neighbors unless you’ve got a good reason, and if you do make a social call, keep it brief. Standing in the living room in his Carhartts and Bean boots and stroking his Abe Lincoln beard, he’d talk weather and boats with my hopelessly nerdy dad, the scientist, born and bred in the city. In turn, my dad had great respect for Walt, a man so unlike him.

I can say that Walt had a studied indifference to the modernity, the urban rush, and the comings and goings of us summer people. I think he was grateful for his boat and traps, things that protected him from a rapidly changing world. Practicing a kind of Olde American zen, Walt seemed to regard people like us, people from away, like the tide. We came and we went. Others would come when we were gone. I suppose that’s one benefit to having a long family history rooted to one place: You get to observe the human struggle over the centuries from a remote and steady perch.

My mother spent much of her time trying to connect with the people of the island. She was eager to help. When she learned that a couple who owned an organic farm on the island were struggling, she helped them write a business plan to get grants, connected them with a graphic artist who could create attractive packaging for their homemade goat-milk soap, and paid for the installation of underground pipes to get water from their house to the barn.

To me, being a good “person from away” meant accepting Maine as it was. We paid our taxes and didn’t make demands on the community. We kept our heads down. I’d read on the porch while listening to dragsters racing down country roads and rounds of shotgun blasts echoing through the woods on Sunday afternoons. I’d paddle out into the cove to extricate plastic bottles, rubber gloves, and fishing line from the reeds.

Less easy to ignore, though, were the racist slogans that had recently appeared on sides of barns and road signs, and the Confederate flags that seemed to crawl out of the ground like cicadas during the 2016 election. Maine had been a proud free state during the Civil War, and no state had a higher proportion of men fighting in the Union Army. These Mainers, without hesitation, had signed up to end slavery; we have their letters to prove it. But things were changing fast. In August 2019, after enjoying the local fair for 40 straight years, we decided to skip it. We’d seen enough “Beer, Guns, and God” T-shirts, flags, and hats the year before.

— — —

In the midst of our pandemic quarantine, I took on writing assignments and FaceTimed my daughter, who’d stayed at her dad’s place in the city in case schools started in-person classes again. I implemented mandatory happy hour, just to keep up a routine. Sean and I took walks down the country road during the day. Every night in my dreams, we were shopping or dining or traveling—so pleasant, until I realized in a panic that we were unmasked.

Time was an uroboros. Every day was the same. I wondered what would break the cycle.

Not long into this, Dan, then 44 years old, decided to leave Manhattan. He’d had the same impulse I did—to escape to Maine—but he’d stayed in his apartment until Mayor Bill DeBlasio closed the public schools. His plan was to drive to my parents’ island house with his 16-year-old daughter and their pug. My parents, inching toward 80, remained isolated in Philadelphia.

The whole month leading up to Dan’s departure had been a nail-biter, as he tried to go about his life gloved and masked, disinfecting everything in sight, knowing the pandemic was real long before anyone else did. As a veteran public health worker, he’d been in Africa during Ebola and in Asia during SARS. He has friends in the WHO and the CDC and USAID. He was also immunosuppressed and adhered to the most stringent health protocols. He assiduously followed the news, sending me links to pandemic stories almost daily.

I’d been sending Get out texts to Dan for weeks. Now he was free.

His daughter worried about bringing the virus with them to Maine, which had few cases at the time. I was torn—I didn’t want them risking others’ health—but I also wanted to protect my brother. I knew he’d be careful, but still. Sitting in my quiet house with little to do, I struggled with the ethics of it, thankful that in the end, it wasn’t my call.

As Dan and his daughter made their way up the coast, they texted photos. Both wore the N95 masks he’d bought in Vietnam in January, when everyone there could see the storm coming. They drove for 10 hours straight out of fear of infecting themselves or others. I relaxed when they finally got to the island. They were home. They were safe.

The next morning, Dan texted me: We took a walk last evening and the woods smelled funny. Maybe a chemical in the air or the ground? Like ammonia. Not the pine trees I remember.

— — —

Photo Credit : Hokyoung Kim

My parents and I channeled our fear into action. We contacted the local volunteer ambulance company to inform the staff that Dan was there and might need to be transported at some point. We shared his New York physicians’ contact information. We alerted the local hospital and the Bangor hospital of his condition. The local pharmacist knew too, and arranged for curbside, contactless pickup of medications.

Everyone who might be affected if Dan needed to be moved was informed and prepared.

My parents also asked Dan’s girlfriend, Laura, who’d stayed in New York, to drive to Maine to help. While she was heading up, Dan accidentally broke a pipe, the house being partly in winter mode. He called the plumber my dad had used for 30 years and explained the situation: broken pipe, leaking walls. As a public health professional, he also felt compelled to add that he was probably suffering from Covid.

The plumber didn’t come to service the pipes. Instead, he alerted the sheriff. The sheriff then called my brother and lit into him for coming to Maine. By then, Dan had been febrile for more than a week. “Rachel,” he rasped over the phone during our precious yet brief conversation the next day, “I have no fight left in me. All I could say was sorry. Sorry.”

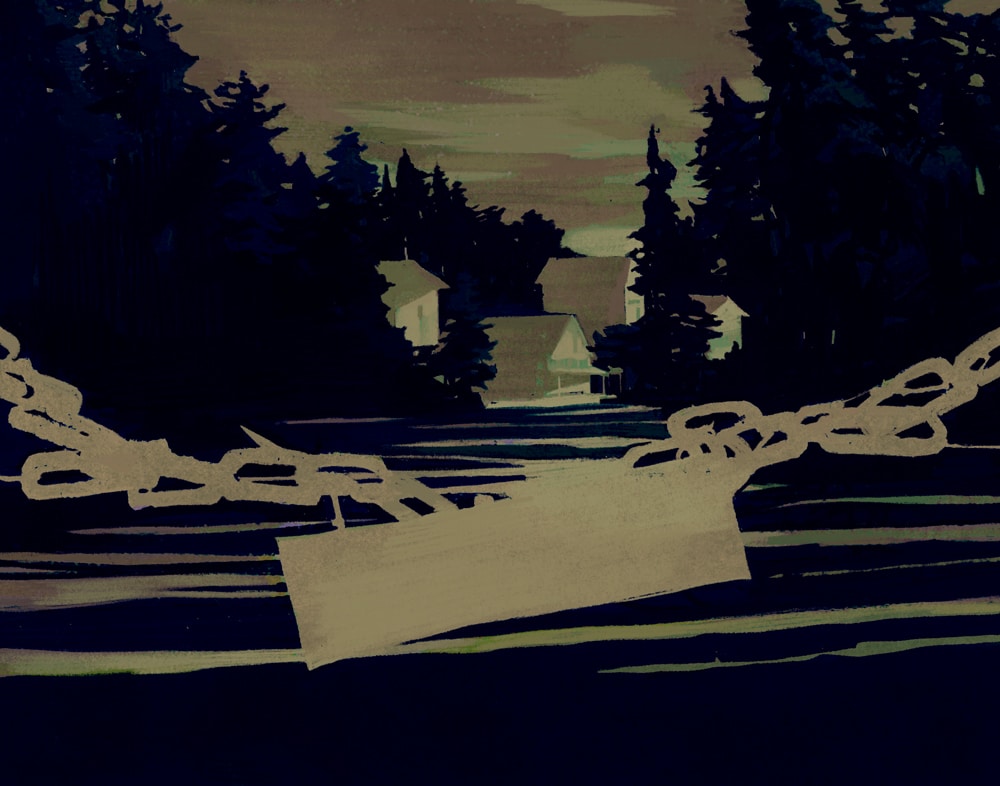

The morning after Laura arrived, Dan’s physician recommended that he take albuterol to open up his lungs. Laura called the pharmacy and arranged for curbside pickup, then started down the driveway to get the meds. Just before reaching the road, she discovered that someone had pulled a chain across the driveway and padlocked it tight, trapping them in.

Apparently, the plumber had taken to Facebook. Someone, probably empowered by news that locals on the island of Vinalhaven had cut down trees to block outsiders from entering town, had taken the law into his or her own hands.

I picked up the phone and called the sheriff’s office, and was transferred to the deputy who had taken the report. Steadying my breath to hide my anger, I asked him for his account of what happened. He spoke to me coolly and professionally. There was nothing he could do about the chaining, he said. There was a time when he would’ve cut the chain himself. But those days were long gone. His department could be sued for property damage, you know? From where he stood, we were strangers, so he didn’t want to get too involved.

I reminded him that we’d lived on the island without incident for 30 years. He answered, chillingly, “None of that matters now.”

In that instant, I recognized the relentless power of fear. During the bubonic plague, mothers abandoned children, husbands abandoned wives, sisters abandoned brothers. Only fear has that kind of power over mankind.

The deputy had only one question for me: “Why did your brother come up here, anyway?”

I wanted to say it was because Maine had always been our refuge. Because Maine had a magic that made us whole. Because if my brother had stayed in New York at the height of the pandemic when the hospitals were overwhelmed, he might have died. I wanted to say that Maine was home.

But I said none of that. He wouldn’t understand. And at that moment, I wasn’t sure I did either.

— — —

Laura, who had no history with the place, dealt with Maine like a true Mainer. She worked the chain free and drove off to get Dan’s medicine. A day later she took him to the local hospital, where he was admitted for four days. In the small facility, he was treated with dignity and concern, which made all the difference. When you are sick with a mysterious life-threatening virus, fear can be as debilitating as fever. The nurses, wrapped head to toe in protective gear equipped with noisy fans, did their best to comfort him. Their kindness allowed him to finally relax and heal.

Dan texted me a photo of himself from the hospital. I looked past the fact that my handsome hiking, canoeing, world-traveling brother was thin and pale propped up on a pillow in a blue hospital gown and yellow surgical mask. All I saw was that he looked … alive.

By early April, he was pretty much himself, working day and night on Zoom calls with his public health teams in Africa and Asia, fighting to protect marginalized populations, as he always has. He even called the sheriff to let him know that he’d recovered and to volunteer to assist the afflicted or elderly, offering his presumed Covid immunity in service to the county. Dan later told me that the sheriff seemed genuinely grateful for the call.

— — —

On the evening of April 9, I gazed across our pond watching the trees turn a dusky blue and was surprised to see big, wet flakes slapping against the window. A heavy snow had begun. It stuck to the pine boughs, drawing them low in graceful arcs. By the time we had cleared the dinner table, the entire scene was thickly blanketed in white. We hadn’t had much of a winter until then. It felt as though Mother Nature was taking a deep, cooling breath.

Around 8 that night, the power went out. Sean’s house ran on electricity, but he didn’t have a generator. I started a fire in the wood stove and used snowmelt to flush the toilets. I filled buckets with snow and squeezed them into our pandemically packed fridge and freezer. I lit some candles and pulled up the covers. But without the Internet, neither Sean nor I could work. More than 180,000 families lost power during the storm. It would be a week before our electricity was restored. We could fight off the cold with the wood stove but the inability to teach his 10 classes online made it impossible for Sean to stay. We packed up the Subaru once again.

I’ve left Maine a thousand times before, always with a faint sense of sadness and longing. That day, I felt only relief. I was escaping from Maine. In the city, there’d be no question of belonging or not belonging. I see strangers every day in the streets, on the sidewalks, in stores, and in the hallway of my condo building. We would wear masks. We’d quarantine. We’d be fine.

Throughout the summer, I followed Maine’s Covid cases from my Boston apartment. Governor Janet Mills issued social distancing and mask mandates early on, and Nirav Shah, the director of the Maine CDC, issued folksy, frank updates that made him a minor celebrity. People took the science seriously. I was right—Mainers were survivors after all.

In the end, outsiders like us wouldn’t be the problem. In early August, a Sanford, Maine, pastor who called masks a “socialist platform” officiated a 65-person wedding in Millinocket. This one event resulted in more than 140 Covid infections in Maine and at least three deaths. It became national news. (Then again, maybe outsiders were the problem: The pastor had moved to Maine from North Carolina in 1994, bringing his ideas of faith, politics, and science with him.)

The desire to belong is very different from actual belonging, especially in a place where “from away” can cling to a family for generations, like an epigenetic marker. You can say I belong here. But it’s never really true. I envy the deputy’s firm belief in his people. His sense of belonging comes to him so easily. If the islanders broke the law, they did it with the best of intentions. In his world, the islanders had every right to defend their community from outsiders, even if those outsiders lived among them. Chaining the driveway was the most pragmatic way to contain the problem. I get that.

But months later, I called Laura once again to confirm that I had the whole story. I wanted to make sure I wasn’t missing anything. This time, she added a single detail that changed my entire understanding of the events.

It turns out that the person who tried to prevent my family from leaving our house had hung a handwritten note on the chain, which somehow made the act less cruel, more human. The note read simply yet poignantly, “Stay home.”

When I read this article in my Yankee there were a number of sentences that went down my back. I thought then that the writer was easily offended, closed-minded and elitist. She belonged in Boston.

I am a born Yankee, but I’ve lived around the country. We own a house on the Cape and a house in Florida. Our family, like so many after World War II, has Northern roots and Southern roots. I’d like to think that our children benefited from a wider family history. From ancestors who supported both sides of a once divided country. It seems to me that there is a sincere effort, led by elites, to once again divide our country. I’m pretty sure Rachel Slade and I would choose opposite sides.

Interesting, Bette M. I appreciate your desire to help unite our country – one that feels increasingly polarized in the last two decades. Of note, while my understanding of US history is limited to what I learned in high school, a few non-fiction texts, and current debates among historians, I understand that the main issue that drove northerners and southerners to take sides was slavery: the south fighting to maintain slavery, and the north fighting for emancipation of those enslaved. Of course, as with everything, there were various issues and nuances at play, but at the core, would you disagree with this? With that in mind, given your comment above, I would think both you and Rachel would likely side with whatever movement was one of solidarity, mutual respect, and equality.

wow! Talk about “elites”! A house on “the CAPE” and a house in Florida?!? Sounds pretty “elite” to me!!

Never mind…I don’t see where my comment needs “ moderation. Don’t print it; it’s sad to me that Yankee would print a comment so filled with dog whistles! I read Rachel Slade’s essay as a beautifully written account of an experience she and her family had. I appreciate lovely writing… it’s one of the main reasons I subscribe to Yankee.

When I read this first in YANKEE Magazine, and again here, I probably identified with Rachel Slade more than she could imagine. I can’t help but wonder if her family’s home was on the same “… island halfway up the coast …” as the one my husband and I chose to move to from the DC area in the 1980’s. A couple of small town kids, we had endured city life for years and were ready to retire to a slower-paced area; we had visited Maine in all seasons – including black fly and mud! – and loved it. We met some lovely people and some not-quite-so-lovely, as you’re going to find everywhere. We tried to get involved in local volunteer life; Yankees know how nearly everything is run by volunteers in places like that island that was so much a part of our lives for about 30 years. Shortly before he died, one of the world’s best neighbors, fortunately one of ours, told us that, much as we tried to get involved and regardless of the respect we might have earned, we would always be “from away.” He was right. We finally went “away.” I will always love that island and will never forget those years we spent there, and will always consider it our “querencia”. It’s sad that we were destined to always be “from away.”

I fail to see why this article made the editorial cut. My family lives in Maine. I lived there for most of my life before moving to the west coast. It is a rural state with limited healthcare infrastructure and a large elderly population. Maine is not, as the author insists, a magical playground where she and her family can escape to their second home during the worst public health crisis in a century and face no consequences for doing so. Mainers are real people. They are not the stereotypes harmfully perpetuated in this article: the simple lobster fisherman, the poor and clueless farmers with no business acumen, the racist hillbillies toting the Confederate flag and drag racing down dirt roads. Public health messaging was, and continues to be abundantly clear: do not travel outside of your local community unless it is essential.

Her brother, who works in public health, disregarded public health warnings and travelled to an island community, putting those around him (the plumber, the health care workers who treated him to name a few) at considerable risk of contracting a deadly illness. I can understand publishing this article if the author acknowledged that this was wrong, but she is defiant. How dare these Mainers not welcome my family with open arms during a deadly pandemic, she asks. How dare they ruin my romanticized vision of Maine as a haven where I can go and be carefree while these simple folk live their lives around me, she implies.

This is a really disappointing article. As someone who hasn’t travelled during the pandemic, particularly someone who hasn’t travelled to Maine where my home and my family are, it is especially offensive. It seems Yankee Magazine’s editorial standards have slipped. Perhaps they are so desperate for content they are willing to publish such a disingenuous and insulting piece laden with one dimensional stereotypes and hollow virtue signalling.

I completely agree. This whole piece is rife with entitlement and stereotypes. There is nothing in here to add anything beneficial to anyone’s lives.

YANKEE, this is irresponsible work on your part. It shows how out of touch you are with those who are supposed to be your target audience.

The part that really emphasized to me that the author is completely out of touch was her offhand comment that 180,000 households lost power in the blizzard she describes at the end and that because she and her husband were unable to “work without power” they packed up their Subaru and “escaped” Maine. It must be really wonderful to have the privilege of getting in your car and escaping your second home to go back to your primary residence, but what about the 180,000 other households who didn’t have that privilege? It really is a despicable article from beginning to end. Yankee Magazine is supposed to celebrate all things New England, not perpetuate elitism and privilege.

Thank you, so well said. I have just laid eyes on this piece of work and it really doesn’t speak to what Yankee Magazine is, or at least nothing I have ever seen here.

I would love to see a written apology form this author for her careless behavior and I quote ” on the Sunday after our arrival we did a panicky Hannaford shop”

and put every patron and employee at that store at risk. There is no mention of testing before they left, her or her brother, who if he had been tested he would have been positive, or any mention of anyone quarantining. There was a State of Maine mandate at the time for all visitors to be tested on arrival and to quarantine for 14 days, all these steps , according to this article, were ignored.

There should be a written apology to the people of Maine for her careless behavior.

I absolutely agree with you. Well said. Rachel Slade’s family behaved selfishly.

I have lived in a resort area all my life, but not in New England, so was interested in the perspectives of this article. I was shocked at the attitude of the author towards the people of the Maine island after her brother broke quarantine in another state to relocate there. The inference I saw was that he was a professional and knew what he was doing, so it was OK (it’s not). We had the same problem here in Florida at the time, with people flying out of New York to come here to escape the pandemic. It was a huge problem, especially with our high elderly population. Then there was the dig in the article about the pastor from North Carolina bringing his “backward” ways to the community. I don’t think this article should have been published in Yankee.

I am very disappointed that the writer and Yankee Magazine failed to emphasize that everyone in this story was breaking the law. New York was on lock down during a pandemic. These people in the article, no matter what state they were seeking refuge in, were breaking the law when they decided in their selfishness to leave the city.

I’m in complete agreement with the Sherriff, the neighbors and everyone else who felt that Rachel Slade and her family should not have endangered the close knit Maine community.

They had no business visiting there during a pandemic. Shame on them.

I was greatly disappointed in this Yankee Mag hit piece. Basically, this issue was “Vermont, Mass., Conn., and NH are great. Maine sucks.” That might not have been the goal but it damn well felt like to us Mainers. I’d that’s you attitude then, yes, stay the hell away from Maine, Yankee Mag writers.

I enjoyed Rachel’s writing and have felt the same way regarding our “Covid” experience. We live in New Hampshire and have for 20 years. We come from Massachusetts. During the lockdown we would come to Massachusetts to see our children, grandchildren and check on our home there. On our way back north there was a homeowner/landowner who thought it necessary to put a huge sign on the side of route 3 in northern New Hampshire that read “flatties go home”….northern New Hampshire survives on tourism and though we are not tourists ourselves that message of hate and intolerance will never be forgotten either. Let us be kind to each other, our fellow Americans and neighbors. Let kindness and understanding be your guide. After all most second home owners pay the same taxes if not higher than you do and expect no services for that money other than their own personal refuge when they need it. And they paid for it too, no one gave it to them. Be nice…..

This has to be the most tone-deaf privileged account that one could possibly write during the midst of a global health crisis. I am horrified by her portrayal of Mainers as simple or cold or racist. As if they are one dimensional, supporting characters in this woman’s life. She openly admits to knowing resources are spread thin and the communities are small and tight knit, yet has absolutely no shame in using them as an “escape” from a pandemic. She then goes on to justify her family’s actions by pointing out that Mainers, not “people from away” hosted a wedding. This reeks of privilege and utter disregard, Yankee Magazine should be better than this drivel. Rachel, if you are reading this, I hope you find a good therapist to examine your flagrant narcissism. God Bless.