New England Meetinghouses | Sense of Place

Paul Wainwright’s photographs of New England meetinghouses are caretakers of memory and history.

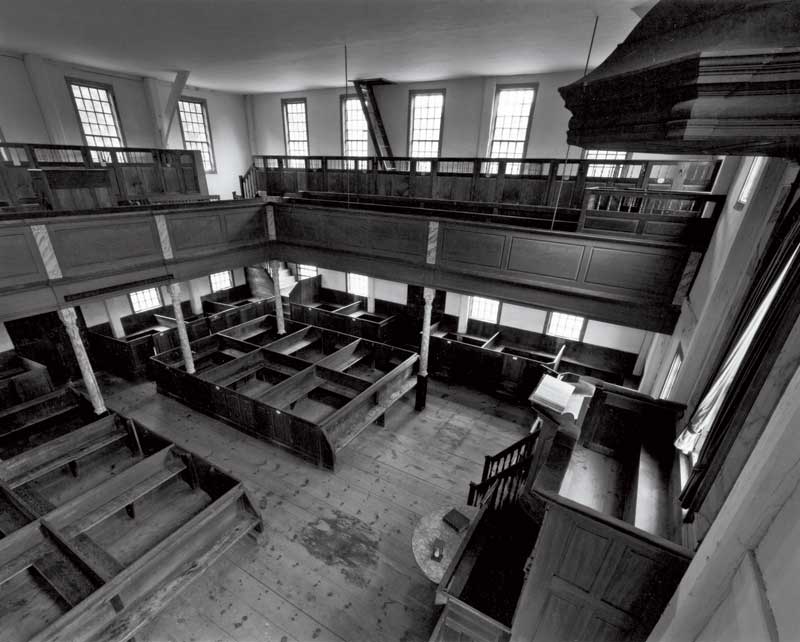

View from the east gallery’s slave pew.

Photo Credit : Wainwright, Paul

Photo Credit : Wainwright, Paul

Arlene Bassett hides from the rain in the doorway of the Old Meeting House in Sandown, New Hampshire, as Paul Wainwright gets out of his car with his camera.

Protruding from the ancient lock next to her is a six-inch-long heavy metal key. It’s a copy of the 1773 original, which is still used by another caretaker.Wainwright is familiar with the interior of the building even before he sees it. All of these old meetinghouses have the same basic floor plan–that is, those that haven’t been modernized. Sandown is a gem in that regard: no heat, no electricity, no signs or ropes telling you where not to go or what not to touch. Sitting in the purposely uncomfortable box pews, staring up at the stern Puritan pulpit, is as authentic a historical experience as you can find in New England, though few choose to experience it.

Arlene Bassett and the other caretakers keep the place clean, but it’s clear it isn’t visited much–not legitimately anyway. “We had a problem with someone, maybe kids, getting in,” she says, pointing to a side door whose bar latch they’d had to block with a nail. She picks up a discarded soda bottle from under a pew and places it with her things to take home.

Photo Credit : Wainwright, Paul

Photo Credit : Wainwright, Paul

That’s part of the reason Wainwright is here. When doing artistic photographs, he uses a 4×5-inch “large format” wooden field camera, but today he’s making just quick photos with a digital camera. Later he’ll upload them to a Web site he created to raise awareness of these meetinghouses. What started as a purely artistic exercise for him has ballooned into something of a crusade. He has always been drawn to old structures. “It loses its artistic appeal to me as soon as you put plumbing in a building,” he jokes. He photographed his first meetinghouse, in Fremont, New Hampshire, in 2004 and fell in love with its forms and shapes: the grain of the wood, the waves in the windowpanes, the lines of the sounding board above the pulpit. But as he began researching where to find meetinghouses, he got wrapped up in their story.

Here, in these churches-turned-town-halls, is where democracy was born for the common man. With all due respect to the Founding Fathers, our nation couldn’t have come into being if it weren’t for the simple farmers and families who erected these humble wooden buildings and took on the responsibility of governing themselves. The Declaration of Independence, after all, was not in itself a new idea but a well-worded acknowledgment of the quiet revolution that had already happened, built on the echoes of ministerial elections and municipal debates that were taking place in buildings like this.

“My photographs aren’t intended necessarily to document what these buildings look like,” Wainwright explains. “They’re meant to tell how I feel about them.” Pursuing his idea, Wainwright tracked down meetinghouses across New England, many of which were just as untouched and utterly forgotten as Sandown’s. He found no organization of meetinghouse caretakers, and the addresses and contact numbers in his notes represented the most complete list of its kind. He published that information and some of his photos online as a first step toward bringing meetinghouses back into New England’s consciousness.

Photo Credit : Wainwright, Paul

Photo Credit : Wainwright, Paul

Along with gallery showings and his forthcoming book, A Space for Faith: The Colonial Meetinghouses of New England, scheduled for release by Peter E. Randall Publisher in 2010, Wainwright hopes his work will generate the interest these buildings deserve. “One reason for good art’s existence is to educate or teach or motivate people,” he says. “I think I can do that through my photography.” Once he’s finished photographing the Sandown meetinghouse, Wainwright packs up his camera and leaves. Arlene Bassett picks up the soda bottle and follows him. She closes the door and turns the heavy metal key in the lock, sealing away the history until someone else shows enough interest to ask to be let in.

SEE MORE: The Colonial Meetinghouses of New England

Justin Shatwell

Justin Shatwell is a longtime contributor to Yankee Magazine whose work explores the unique history, culture, and art that sets New England apart from the rest of the world. His article, The Memory Keeper (March/April 2011 issue), was named a finalist for profile of the year by the City and Regional Magazine Association.

More by Justin Shatwell