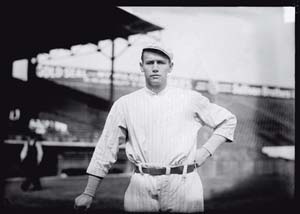

Baseball Cards | Antiques & Collectibles

Once upon a time, “take me out to the ball game” seemed like such an innocent request. The song’s refrain asked for nothing but a carefree afternoon at the park, eating Cracker Jack and delighting in the sheer joy of a baseball game. I don’t recall any verse about luxury seats, or paying $25 to […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanOnce upon a time, “take me out to the ball game” seemed like such an innocent request. The song’s refrain asked for nothing but a carefree afternoon at the park, eating Cracker Jack and delighting in the sheer joy of a baseball game.

I don’t recall any verse about luxury seats, or paying $25 to park the car. Red Sox fever is rampant, so perhaps I’m the only one who feels we’ve lost the true spirit of America’s favorite pastime. I want to believe that early on, baseball wasn’t just about money.So I took my premise of purity to Garrett Sheahan, lifelong Red Sox fan and collectibles expert at Skinner, Inc. He removed my rose-colored glasses. He said that money has been a part of baseball since the beginning. Take, for example, baseball collectibles. But who cares that their invention was totally commercial in nature? They’re still a fun slice of American history.

As early as the late 1800s, baseball collectibles were the brainchild of savvy marketers who gave away baseball cards and other goodies as premiums with product purchases. The best example is tobacco baseball cards. (Yes, kids, you heard right: tobacco. Maybe our collective conscience has actually improved since then.)

In the 20th century, baseball–and Americans’ enthusiasm for it–thrived. The collectibles field grew to include programs, score cards, ticket stubs, trophies, pennants, megaphones, and game items such as autographed equipment. By the 1950s, fans showed their allegiance with collectible glassware, tie tacks, cufflinks, lapel pins, bobblehead dolls, and other souvenirs. For today’s collectors, there’s plenty to choose from, and the price range couldn’t be wider: Ticket stubs and baseball cards start as low as $10, while autographed balls, bats, and uniforms sell for five and six figures.

Red Sox collectibles can demand a premium price, especially in the New England market. In April 2007, Skinner sold a 1955 Ted Williams game-worn jersey for more than $30,000. Even with paper items, prices can soar when rarity, historic moments, or star players are involved. For example, the most famous tobacco baseball card in existence (and one of the rarest), a mint-condition 1909 Honus Wagner, just keeps getting pricier: It was last sold for $2.8 million.

But beware, collectors–this crazy market is rife with fakes, forgeries, and worthless limited editions. Sheahan’s best advice? Avoid items from later than the 1960s, especially baseball cards. During the ’70s and ’80s, as prices for historic collectibles skyrocketed, those savvy marketers were at it again, printing thousands of baseball cards, which were sold as “collector sets.” Fans snatched them up, hoping values would rise; they didn’t. Provenance is also critical. Knowing that an item has been stored in an attic since the 1950s tells you it’s probably the real deal.

Maybe baseball has always been more about business than pleasure; more about ruthless competition than good-natured fun. I guess that’s okay. After all, it’s America’s national game, and what are we if not plucky entrepreneurs who are in it to win?

If you’re in it to win, don’t buy baseball collectibles for their investment value. For true fans, collecting baseball’s past should be a search for authenticity and a tribute to historic teams and heroic players. Collecting is about love of the game. That’s the big payoff.

Catherine Riedel represents Skinner Auctioneers and Appraisers of Boston and Bolton, Massachusetts. 617-350-5400, 978-779-6241; skinnerinc.com

I have quite a few of these vintage baseball cards. What are they worth?

One is of Babe Ruth