National Tennis Court in Newport, RI | Real Tennis, Anyone?

Yankee Classic Article from March 2000: In which the author discovers an unexpected knack for a medieval game played inside one of Newport, Rhode Island’s most obscure and discreet institutions. I have just hit the nick for the third time, and George Wharton, my instructor in the ancient and royal game of court tennis, is […]

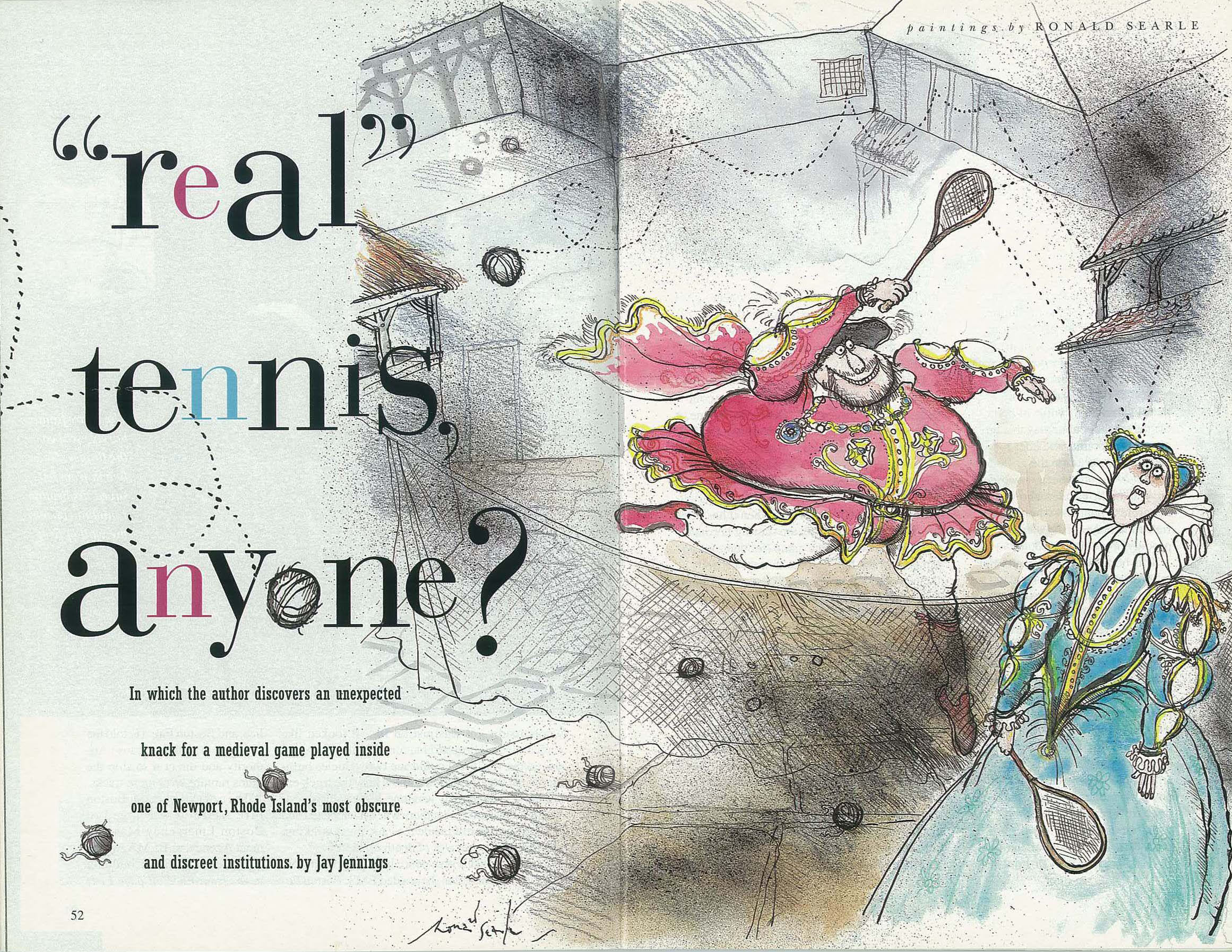

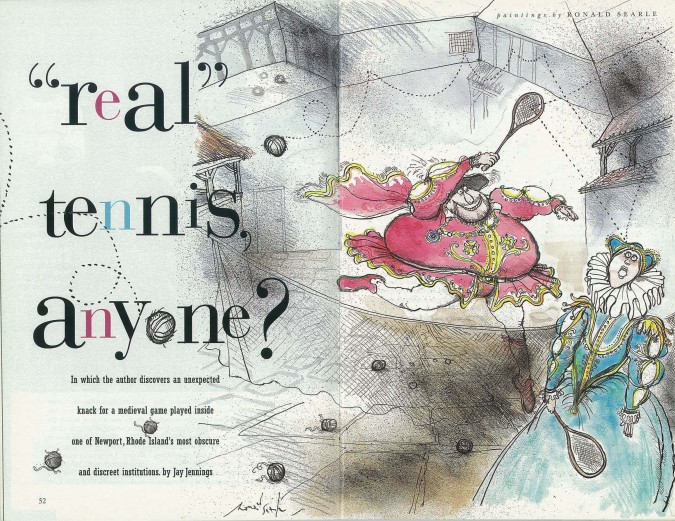

Yankee Classic Article from March 2000: In which the author discovers an unexpected knack for a medieval game played inside one of Newport, Rhode Island’s most obscure and discreet institutions.

I have just hit the nick for the third time, and George Wharton, my instructor in the ancient and royal game of court tennis, is slightly nonplussed. Before that, I smacked a couple of balls off the tambour at unplayable angles to win points, and later I socked one right into the grille for a winner. If you’d been watching us, you might wonder who was the professional and who was the first-time player. I am clearly a prodigy, a prodigy at 40.

This bodes well for my attempt to infiltrate the highest levels of Newport society and, eventually, the royalty of England. In his exhaustively researched (and very heavy) book, Tennis: A Cultural History, Heiner Gillmeister states that contemporary court tennis “possesses a not inconsiderable amount of snob appeal.” Exactly what I am looking for. And, fortunately, Newport is one of only two places in the country where any schmo like me can plunk down his money and get a lesson or court time. The only other court tennis court in New England — there are only ten in the United States — is in Boston, at the tony Tennis & Racquet Club, where someone like me would nor normally be invited to the cloakroom. With my newfound skill in this high-class game, I can see the doors of the T&RC opening wide.

Devotees say that court tennis — or “real tennis,” as it’s called in England — is a combination of tennis, squash, and chess. To me, it seems more like tennis, squash, and pinball. The court is symmetrical, with all manner of possibilities for knocking the ball at strange angles or into openings along the wall. There’s even a net-covered opening — the grille — in which a bell rings when it has been hit. The rules are arcane, the scoring is complex, and mastering the game (for some) is agonizing. In the locker room that serves both the National Tennis Court (as the court tennis court in Newport is called) as well as the grass tennis courts of the Newport Casino Lawn Tennis Club, I spotted a sign that read: “For sale: Gray’s Court Tennis Racquet. Used once. Call Marty.”

Before he gave up after one try, Marty should have known that guys with names like Marty don’t play court tennis. Its players usually have two middle initials, e.g., Haven N. B. Pell, the president of the club outside Washington, D.C.; or some kind of title like Prince (Edward, of England’s royal family); or a foreign article or preposition as part of their names, like Peter di Bonaventura, the head pro at the Greentree court on Long Island. Past champions have included such examples of American corporate tycoonery as Jay Gould, Payne Whitney, and Ogden Phipps (of Bessemer Steel). From now on, I plan to be known as Viscount Jay L ‘Jennings.

The game is said to have originated in medieval monasteries, but the sport of monks gained its social oomph when it became the sport of royalty and their hangers-on. In Baldissare Castiglione’s The Courtier, a guide to proper behavior published in 1528, he highly recommends the game: “It is a noble exercyse and meete for one lyvying in courte to play at tenyse, where the disposition of the bodye, the quicknesse and nimblenesse of eyerye member is much perceyved.” If Castiglione were to tum up in Newport today, racquet in hand, he would find the game he knew as “tenyse” virtually unchanged. In fact, a 1632 picture of a tennis court in a book from the Bibliotheque Nationale de France in Paris strongly resembles the court in Newport, with its second-story windows and beamed ceiling. (No, my editors didn’t pony up a trip to France; the picture was on the excellent court tennis Web site at www.real-tennis.com.) And the court on which England’s Henry VIII played at Hampton Court in the 16th century is stillI used for “real tennis.”

Legend has it that the game’s idiosyncratic layout comes from the monastery courtyards where it was first played. That claustrophobic charm is preserved in the game’s most distinctive feature, a sloping roof, called the penthouse, which runs along one side wall and both end walls. A proper serve must bounce along the side wall penthouse roof. In 1996, at British championships, a player was accused of ” polishing the penthouse,” supposedly to gain advantage on the serve. The opposite side wall is straight and high except for a small outcropping on the receiving or ” hazard” side called the tambour, which ricochets the ball at odd angles. Just beside the tambour on the receiver’s back wall is a small windowlike opening called the “grille,” which in Newport is covered with Plexiglas (or Plecksiglasse, as Castiglione would have called it), and which produces a winning point (and a loud noise) when hit.

While I was toying with Wharton during our lesson, I smacked a ball right into the grille, much to his surprise, after which I raised my arms in triumph and did a little dance. This, I surmised from the frown on Wharton’s face, was not quite cricket in court tennis. In fact, rules of conduct are very important to the game, and one of the most important involves changing sides. The person on the hazard side always comes around the net post first, thus avoiding nasty confrontations. If you violate this rule, Wharton says (reading my mind), “the marker [a.k.a. the referee] might not kick you out, but it would be a serious violation of etiquette.”

Stern etiquette, however, doesn’t preclude eccentricity, a court tennis tradition. One of the game’s (and Newport’s) most enthusiastic leaders was James Van Alen, a three-time national singles champion in court tennis, who also founded and was president of the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport. Van Alen invented the tie break in lawn tennis and was often seen courtside at the U.S. Open with a self-designed flag that he would stand and wave every time a set went to a tie break.

More recently, the game lost one of its biggest supporters with the death of Clarence (Clary) Pell, father of the aforementioned Haven N. B. and first cousin of former Rhode Island Senator Claiborne Pell. Clary Pell, who was the force behind the restoration of the Newport court in 1980, insisted on calling lawn tennis “lawners” and court tennis just plain ” tennis” in deference to its historical precedence. Newport now hosts a doubles tournament named after him — “The Pell Cup.” Following the lead of these two pioneers, and to honor Henry VIII (a big player when he was between wives), I plan to play all my future matches in doublet and hose, complete with Nike swoosh. I can see it now: Air Hose.

For years I toiled at ordinary lawn tennis, suffering the occasional McEnroe meltdown when too many balls hit the net tape and fell harmlessly on my side of the net. But in court tennis, I have found my game: Most mis-hits are still in play – they may sail onto the roof at either end and roll down for your opponent to take a swing at or bounce high off the side wall, but they’re still in play. “Unlike lawn tennis,” says Wharton, “in court tennis it’s very rare that a ball is unreturnable.” And when you do connect solidly, the squashlike racquets are strung so tightly that it feels more like hitting a golf ball than a tennis ball.

Some former lawn tennis players are so bewitched by court tennis that they never go back. Berry Packham is an accountant from England who now lives in Newport and used to play “lawners” five times a week. One fateful day he found all the regular tennis courts occupied, and somebody suggested he go have a look at court tennis. “I haven’t been on a lawn tennis court since,” he says.

These days it’s difficult to find a court tennis court unoccupied. The sport is growing in popularity in England, partly because of Prince Edward’s advocacy. “Courts in England are booked from 8:00 A.M. to midnight,” Packham sighs. The National Tennis Court at Newport, adds Wharton, is booked from 55 to 80 hours a week, and the club employs three pros. In the hour that I sat in Wharton’s office, the phone rang at least a dozen times with bookings. The small, cluttered room also functions as the pro shop, snack bar, social room, training room, and ball-making facility. In fact, almost every spare moment of a court tennis professional’s day is spent making balls — a cork core is wrapped tightly with cloth tape, which is then secured with string, after which two hand-cut hourglass-shaped pieces of felt are nailed into place. Finally, the covering felt pieces are hand-stitched together.

“Is the thread special-ordered from the sewing room at Buckingham Palace?” I ask Wharton.

“Actually, it’s CVS dental floss,” he says. “Our favorite.”

The floss remark worries me. Though I obviously have a God-given gift for the game, my real purpose is to hobnob with the nabobs in Newport. But what sort of snob would be seen hitting a ball laced with dental floss? I give Wharton a wink. . “Say, old man,” I say hopefully, as I push my straw boater back off my forehead, “isn’t this game “elitist’?”

He laughs. “Anything that’s rare gets the tag ‘elitist’ put on it. Do you have to be wealthy to play court tennis? Not at all. We sort of get a bad rap, because of the nature of where the game is, in the clubs. The game itself would appeal to anyone. This is not an elitist club.”

Darn. Despite my uncanny knack for hitting the nick (that is, striking the ball so that it lands where the end wall meets the floor and rolls rather than bounces), I must give up court tennis. Newport’s National Tennis Court is too plebian for my purposes, I realize, as I trudge away from Wharton’s non-elitist office. Outside, I consult my map of Newport. Now where is the Newport Yacht Club? Surely a $30 million America’s Cup boat could use a crew member who can polish a penthouse and bang the grille with such ease.