Madame Sherri | New Hampshire’s Most Eccentric Resident?

Madame Sherri’s Castle Ruins Take a drive down the Gulf Road in West Chesterfield, New Hampshire, some time. It’s an enchanting landscape — horses running through sun-drenched fields, steep green hills dotted with small white houses. Further down the road, you’re enveloped by woods and wetlands. The driving here is somewhat questionable, and you have […]

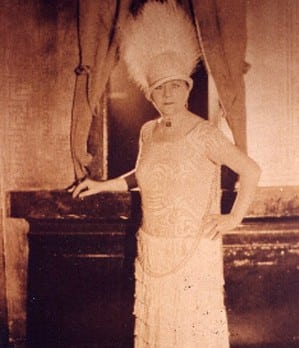

Madame Sherri

Photo Credit : Photo Courtesy of Brattleboro Historical Society

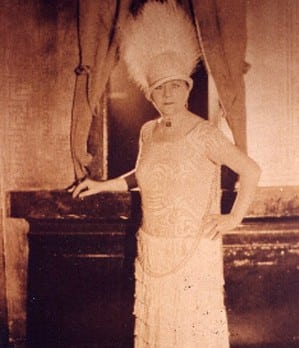

Photo Credit : Photo Courtesy of Brattleboro Historical Society

Take a drive down the Gulf Road in West Chesterfield, New Hampshire, some time. It’s an enchanting landscape — horses running through sun-drenched fields, steep green hills dotted with small white houses. Further down the road, you’re enveloped by woods and wetlands. The driving here is somewhat questionable, and you have every right to be concerned about your vehicle’s undercarriage. But at last, you find the car park for the Madame Sherri Forest.

You disembark, walk over a small bridge traversing an algae-choked pond, travel up a short path, and stop. There, in front of you, is a massive stone staircase, seemingly leading into thin air. Behind are the remains of a luxurious house, and a huge lawn, steadily being reclaimed by the forest.

Welcome to the world of Madame Sherri.

Of all of the local legends I’ve encountered, nothing seems to have hit the popular nerve as much as this particular eccentric New Hampshire resident. When you mention Madame Sherri — some five decades after her demise — someone in the room will suddenly speak up, and offer an anecdote. The thing is, though, as with most legends, many of the stories are spurious. There are tales of her running a brothel, of hobnobbing with Al Capone and Supreme Court justice Harlan F. Stone. Gleaning the truth from these tales is a difficult task, to say the least.

Madame Sherri was born Antoinette Bramare in 1878 in Paris. That year also marked a peculiar astronomical phenomenon; for a week, a weird corkscrew-shaped pillar of light appeared above the city’s skyline. She could not have asked for a better entrance.

Sherri originally trained as a seamstress, but also performed on stage as Antoinette DeLilas, dancing in some of the trendiest clubs in France.

In 1909, she struck up a relationship with one Anthony Macaluso, who was traveling under the pseudonym Andre Reila. Macaluso was an American expatriate who had fled to Europe after being indicted in an infamous blackmailing case. The two hit it off immediately, and got married.

The couple decided to return to America in 1911, boarding the White Star liner Oceania, headed for New York City. As Macaluso was still a fugitive, an elaborate cover story was concocted, involving a prominent Italian diplomatic family and an awkward meeting with Madame’s new in-laws. The ruse worked, and the Big Apple press ate it up. “Tears of bride melt young Riela’s family,” ran the headline in the New York World, describing the fictional encounter on the dock.

Andre and Antoinette settled into New York society, and opened a millinery on 42nd Street, designing costumes for the brightest lights on Broadway, including outfitting the Zeigfeld Follies.

It wasn’t until July of 1912 that Reila’s past came back to haunt him, due to a genuinely astonishing coincidence. On Wednesday, July 3rd, he told police at the West 57th Street station that jewels, worth between $12,000 and $30,000, had been stolen from his wife by a servant. Due to the enormity of the theft, the Deputy Commissioner assigned one Captain Gloster to the case, who in turn secured the help of Detective Fitzsimmons, from the District Attorney’s office. While interviewing Reila, Fitzsimmons had a sudden revelation, and yelled, “you’re Anthony Macaluso!” before promptly placing him under arrest.

Reila was incarcerated in the infamous New York City prison, “The Tombs,” for a few days, before being released on bail. Ultimately, the charges against him were dropped, due to lack of evidence.

With his name cleared, Reila began to pursue his dancing career in earnest, while Antoinette continued designing elaborate costumes for the stage.

In 1916, Antoinette decided she needed a new, flashier name to attract business. She had always been an avid admirer of Otto Hauerbach’s play, “Madame Sherry,” and decided to adopt the moniker for her husband and herself. Accordingly, on November 10th of that year, she marched into the New York City Registry and made arrangements to open a business under the name “Andre-Sherri.”

The next eight years saw the couple realizing tremendous success, as Andre took his dancing revue onto the Vaudeville circuit, complete with magicians, comedians, and a bevy of scantily-clad young ladies. It was during this time that they began their connection with Charles LeMaire, a pianist who decided to pursue a career in costume design. Taking the young man on as a counter assistant, they encouraged him in his new vocation, and he soon found himself working with Flo Zeigfeld. Eventually, his success would take him out to Hollywood, where he was employed by 20th Century Fox.

All of this good fortune would come to a crashing halt in 1924. Plagued with venereal disease, Andre went blind and insane, and was admitted to the Manhattan State Hospital. On October 19, he finally passed away.

To say Sherri was shattered by this turn of events would be an understatement. New York’s night life no longer held the allure it once did, and she began to look elsewhere for solace. It was at this time that she befriended stage actor Jack Henderson, who told her he owned a house on the Gulf Road in West Chesterfield, New Hampshire. He started to invite her along to his parties, which were booze-fueled affairs featuring naked girls jumping out of cakes.

Over the next five years, Sherri was in regular attendance at these celebrations, and by 1929, decided to pull up her New York roots and move to the Granite State for good. Through Henderson, she had met a neighbor, George Furlone, who owned a small farmhouse on a 70-tract. She purchased it, and then began buying adjoining vacant properties, eventually acquiring 600 acres.

It was at this point that she began constructing her infamous “castle.” Employing local handyman Paul Welcome to oversee the construction, she brought in stonecutters from Fitchburg, Mass., and laid out her grandiose plan.

The problem was, she had no blueprints of any kind. She would just traipse along the lot, putting down pegs where she thought each aspect of the house should stand. The workers were baffled, but persevered.

What rose from the forest floor was something the like of which New Hampshire had never seen. The house looked like a cross between a Roman ruin and a French chalet. In the cellar, there was a cozy little bistro, with half a dozen tables, draped with red cloths. The main floor was a huge bar, which one entered between two huge trees, growing through the roof. The third floor held Sherri’s private quarters, accessible by a huge stone staircase that ran up the side of the house.

This was where Sherri held her parties. Although she still lived in the tiny farmhouse across the road, the castle was always available for huge shindigs, as her New York friends drove into town, and celebrated the night away. Sherri was always in the middle of it, holding court in her massive cobra-backed chair. She was constantly chain-smoking, but only lit one match a day; each succeeding cigarette was ignited off its predecessor.

The scandals didn’t stop there. Sherri had purchased a 1927 cream-colored Packard from the State Department, which she used to tool about town — usually in the company of several beautiful young people — attired in a large fur coat, with not a stitch on underneath. On these trips, she was also invariably accompanied by a small monkey on a leash.

Madame Sherri paid for pretty much everything with cash, which she would pull either from her cleavage, or a garter belt strapped to her thigh. As a matter of fact, she seemed to take a perverse delight in shocking as many of the local merchants as possible.

Of course, the party had to eventually come to an end, and Sherri’s long decline into abject poverty began shortly after the end of World War II. It appears that Charles LeMaire had been subsidizing her extravagant lifestyle for decades. Now, however, the checks had stopped coming in, and Sherri had to rely on the very neighbors she had been scandalizing over the years. She also concocted various schemes to recoup her fortune, including turning the castle into a nightclub and selling mineral rights to the property. Unfortunately, all of these attempts came to nothing.

It was about this time that Madame Sherri became a Jehovah’s Witness, and decided to move to the Parker House in Quechee, Vermont, at the invitation of Mr. And Mrs. Wilfred Childs. She spent six months living there, before deciding to return to West Chesterfield, New Hampshire.

When she came back to the castle, in the spring of 1959, she was horrified. The house had been completely trashed. Her priceless porcelain had been used as target practice, the local high school kids had made off with her cobra-backed chair for use in the junior prom, and the front door had been ripped off, utilized as a car jack. Sherri ran from room to room, screaming in French and English. “This was our love nest!” she howled, before fleeing from the house. She was never to enter it again.

Sherri then moved into the Maple Rest Nursing Home, at the invitation of Walter O’Hara, an old acquaintance who had provided her with bootleg liquor during Prohibition. Sadly, she was unable to pay for her keep, and, in 1961, she was sued by the City of Brattleboro on behalf of Mrs. O’Hara, to the tune of $800.

Sherri had finally hit rock bottom. Brattleboro attorney John S. Burgess was contracted to act as her guardian on a pro bono basis, and she moved into the Poor Farm on the outskirts of town.

The end came for Sherri’s beloved castle on October 20, 1962, when it burned to the ground, leaving only the stone foundation behind. Far from being concerned about this turn of events, she only basked in her brief return to notoriety.

On July 16, 1963, Charles LeMaire foreclosed on the property. A couple of years later, it was sold to local resident Ann Stokes, who was determined to maintain the land in its pristine state. She went to visit Sherri, in order to tell her that area would be preserved; sadly, she was too deep in dementia to really understand what she was being told. “Tell me something nice,” she kept telling Stokes. “Tell me something to make me happy.”

Sherri expired on October 21, 1965, ironically on the very same day that the sale was finalized. Ann Stokes hung onto the property until 1998, when, tired of cleaning up beer cans and rubbish, she turned it over to the New Hampshire Society for the Preservation of Forests, which maintains it to this day.

Visiting the site today, it’s easy to imagine it in happier times. The staircase still stands, mute testimony to Madame Sherri’s glory days. You can almost see her coming down the stairs, dressed in the height of fashion, crowned by a hairdo that seemed to reach to the heavens.

“Bebes!” she would cry to the arriving guests. “Mes cheres! Please enter and enjoy yourselves!”

Want to learn more about one of New Hampshire’s most infamous residents? Read the book: Madame Sherri by Eric Stanway.