Clark’s Trading Post | Bear Show in Lincoln, New Hampshire

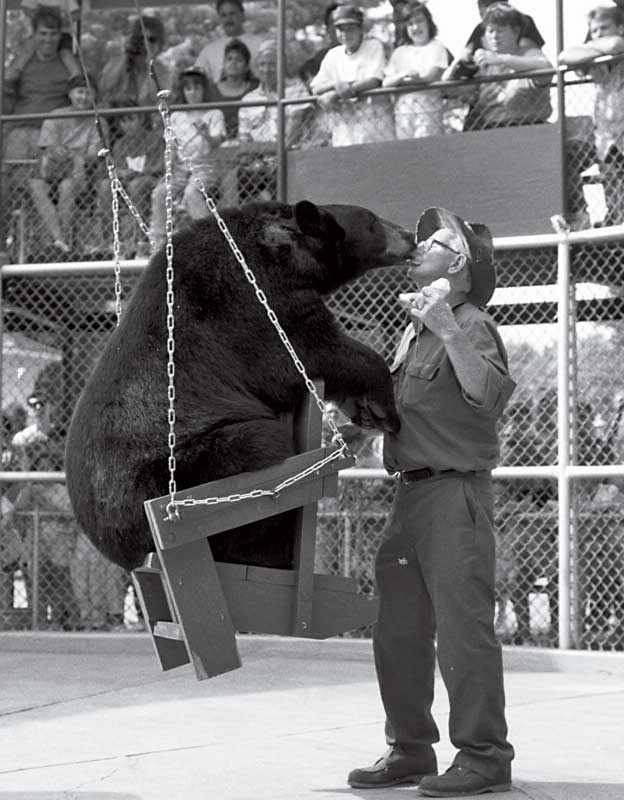

In the ring at Clark’s Trading Post, a six-foot seven-inch, 440-pound black bear named Pemi stands up like a man and tosses a basketball through a hoop. Pemi’s mate, Echo, a 340-pound female, has just finished her act, riding around the ring on a Segway, raising the flag, and dancing. With them is a pixie-like […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanIn the ring at Clark’s Trading Post, a six-foot seven-inch, 440-pound black bear named Pemi stands up like a man and tosses a basketball through a hoop. Pemi’s mate, Echo, a 340-pound female, has just finished her act, riding around the ring on a Segway, raising the flag, and dancing.

With them is a pixie-like blonde woman and a big, gruff, red-headed man wearing an Australian bush hat. Outside the ring, Victoria paces in her pen, rattling the gate. She can’t wait for showtime.One of thousands of acts that have taken place over the past 60 years in this roadside ring in Lincoln, New Hampshire, is underway at Clark’s Trading Post, a place where generations of bears have worked alongside generations of Clarks. The blonde woman and the red-headed man are brother and sister, Maureen and Murray A. Clark, the third generation to raise bears here and the second to train and perform with them.

Founded in 1928, Ed Clark’s Eskimo Sled Dog Ranch gradually morphed from souvenirs and canines to bear acts. The Clarks, it could be said, are perhaps the most ingenious entrepreneurs ever to stake a claim in the White Mountains, substantially influencing the growth of the tourist industry in that region. And, further, it should be said that when you say “the Clarks,” you’re talking about not only the direct descendants of the founders, Edward P. and Florence M. Clark, and their two sons, Ed and Murray, but their offshoots as well: in all, a family the size of a small town, each of whom has shared in the growth of this family empire. But in recent years, only the elder Murray, his daughter Maureen, and his son Murray A. have performed with the bears.

One day last fall, after Clark’s Trading Post had closed for the season and the three bears were preparing for hibernation, the family stopped to tell us about their years here. Talking with these three is like talking to one person. They finish one another’s sentences, which run together as smoothly as the waters of the Pemigewasset River that tumbles behind their legendary Trading Post. Today, this roadside attraction has evolved into an entertainment resort that features not only trained-bear shows but a facsimile 19th-century village, an authentic wood-fired steam train that takes visitors chugging through the countryside, a museum of the family’s own treasures, even a Segway ride. This old-timey place has a history firmly rooted in New Hampshire’s soil.

In 1949, when Murray was 22, he and his older brother began performing with two of the family’s female bears, Ebony and Midnight. Murray stopped performing in 2003, but he has never retired. He’s 82 now–you can still see the bear man in him–and he sits beside the ring, quietly watching Maureen, 50, and Murray A., 40, do things that he taught them and some that he didn’t. He watches every show and still works around the Post, meeting the public and setting up props.

Both Maureen and Murray A. have worked with the bears in one way or another since they were children. Maureen toddled around with her baby bottle alongside the cubs as they drank from their bottles, which made for good snapshots. Since the cubs are raised in the Clarks’ homes, their family albums are full of such images. “You haven’t lived until you’ve raised bear cubs in your kitchen,” Murray the elder often says. “Down come the curtains, off comes the tablecloth, over goes the milk pitcher …”

The cubs ambled around the house and occasionally went for rides in the car. “A bear cub has little rounded ears, small dark eyes, needle-sharp teeth and claws, and the shortest temper on record,” adds Murray A.

Maureen cares for bears of all ages, and the training is nonstop. “When you work with bears, it’s every day, every day, constant, constant, constant,” she says. “People ask, ‘When is it that you’re training the bears?’ The answer is all the time. Every show is a training as well.”

“People ask, ‘How do you do that?’ adds Murray the elder. “Practice! And you take advantage of each bear’s talent. You find their inclinations and then develop those talents, reward them for everything they do. We use no clubs, leashes, whips, sticks, none of that! It’s all animal handling. I’ve been an animal handler since I was yea tall. What works with one animal won’t work with another.”

When he was 16, Murray the elder was mauled by one of his bears: “I was cleaning the pen and I went to pick up something in the gravel, put it in the pail, and I frightened the bear. He turned on me and butchered me up pretty bad … My father saw my clothes torn off, my head bleeding, my scalp all asunder, and he picked up a rifle and went down and shot the bear. That was it.” It was 1943, and at the time there seemed to be no other choice in a desperate situation. Our understanding of animal behavior has evolved since then; today we have additional options and approaches, and no doubt the outcome would be different.

“Don’t ever startle a bear,” Murray explained in a 2001 video interview. “Also, know your bear and its personality. Know where your limits or parameters are in handling them … You cannot handle bears without seeing your own blood. It’s a natural course of events … However, as you raise them, and constantly talk to them and touch and handle them, you then deserve their trust … and that’s what the whole thing is about. You must gain [the bear’s] trust.”

Bears best suited for training are bears descended from trained bears. This is the ideal but not always the case. It’s illegal to take a bear from the wild, but bears occasionally come to the Clarks through New Hampshire Fish & Game or Vermont’s Fish and Wildlife department. Both states rely on the Clarks as they would a rehabilitation center. Moxie came to them that way, a little cub who kept showing up at the home of a woman in northern Vermont. The officials called the Clarks. They rescued the cub, a little tot so sickly the vet told them she wouldn’t live long and warned them not to become attached to her, a tall order for any member of the Clark family.

“She was about the size of a housecat,” Maureen recalls. “She was very sick. We all took turns sleeping with her; even my sister’s dog was brought into it. She feels more than your average bear; if something’s wrong, she gets upset. She always sides with the underdog. We love her. She’s 25 now. But she was in the ring only three seasons.”

That doesn’t matter to the Clarks. Currently the three show bears–Pemi, Echo, and Victoria–perform regularly throughout the summer and fall. But the Clarks keep eight bears altogether; the three oldest live in a large habitat behind Maureen’s home, and the others have moved into new, spacious, natural accommodations nearby. Some of the inactive bears are retired, and some just never enjoyed performing.

“They have to love it,” Murray A. explains. “They have moods, they have emotions. In many ways, they’re very human-like.” Physical attributes help as well. “Bears can manipulate their hands to do things; they can hold, grab, push, shove, stand. They can sit and run on two legs. So with that mechanism already in place, it’s not like working with a cat or a bird. They enjoy going to the next level.”

Not that training a bear is easy. “You put in all this time and energy,” explains Murray A., “and it just doesn’t seem to be paying off, and then one day, like magic, they’ve got it! Repetition is the key. So, I don’t know if it’s a measure of intelligence so much as it is diligence, but they’re all different; you just can’t compare. Just like people.”

Complaints about trained-animal acts have been something of a constant over the years. “We’ve always had that to contend with,” Murray the elder says, “but once they witness a show, that’s it, no problem.”

“Occasionally someone will write a letter,” adds Maureen, “but if you look further, you find that they’ve never been here before.” Murray A. notes, “There’s a whole group of people who object to any trained animals. Seeing Eye dogs, bomb-sniffing dogs, search dogs. They don’t want any animals to be trained in any way.”

To the Clarks, the show is their statement about how intelligent bears are and how profound their relationships with people can be. “We try to educate people as well as entertain them,” Murray A. explains. “The first part of the show, before the bears even come out, I teach things about bears. It’s always been that way.

“After a show, folks tell us that they didn’t want to come because they don’t believe in animal acts, but when it’s over, they’ve changed their minds. They see we’re not only treating them well but that these bears are our friends.”

“A number of hunters have come up after the show,” Maureen adds, “and said that they’d hunted bears, but that now that they’ve seen how smart they are and how close we are to them, they won’t hunt again.”

“Yes,” Murray the elder concludes, “we’ve converted a lot of people.”Each Clark has his or her favorite bear. One of Murray the elder’s best bears was Jasper, a 535-pound male who towered over him when he stood up, which was often. Jasper and Murray had a wonderful relationship. In the show, Murray would sit on the big bear’s belly, walk on his stomach, tickle his feet, all while Jasper was lying placidly on his back, drinking from his bottle.

And then Jasper would pick Murray up and carry him around, give him bear hugs. They’d dance together, cavorting around the ring like best buddies on a lark. At the end of the show, Murray would say, “Ladies and gentlemen, what do you think of my friend Jasper? It’s been my pleasure working with him all these years!”

It was a deep love. Jasper was special–but so are all the family’s bears. “They’re our coworkers,” Murray A. says. “We talk to them as if we’re talking to humans. After a while, they pretty much understand what we want.”

There are no other shows like theirs–maybe even in the world–that the Clarks know of. Murray A. thinks about that for a moment, then says, “This is the center of the universe. That’s what I’ve always been told, and I believe it. There’s nothing else outside of what we have here. This is what we know and where we want to be.”

One of the saddest things that can happen in the Clark universe is the death of a bear. The life expectancy of a bear in the wild is only 6 to 12 years; they may be hit by a car or hunted, or, if they raid trashcans, may ingest plastics and food packaging. Most of the Clarks’ bears, however, have lived two to three times longer than that. One bear, Rufus–Jasper’s brother–lived an extraordinary 38 years.

Inside the park, there’s a small cemetery for bears who have passed on, each grave with a carved tombstone. When a bear dies, the Clarks all grieve. Maureen and her father never got over losing Onyx, Jasper’s son, to liver cancer at the age of 15, in 2002. Maureen wept and wept. “After a while, I just couldn’t cry anymore,” she told a reporter.

Just as with the passing of family members, the legacy of the Clarks’ bears lives with them, always. Right now, Maureen favors Victoria, a youthful 20. “She’s my best friend,” Maureen says. The bears generally work until they no longer want to, and then they retire. “There are certain times when she doesn’t want to work, especially during mating season,” Maureen explains. “However, toward showtime she’ll sit and watch and wait for her turn, pacing back and forth. She’s ready to go.”

Maureen and Victoria share the special relationship that Murray the elder had with Jasper: “She thinks I’m her mother. If another bear starts giving her a hard time, she hides behind me. She’d always think I would protect her. I know she’d do the same for me.”

Once the bears make their nests in their dens and curl up for their winter’s nap, it’s a long stretch without them. “When I miss Victoria, I just go down to her den and wake her up,” Maureen says. “And she’ll sit up like a giant teddy bear. I snuggle in close to her. When I start to leave, she grabs my sleeve to get me to stay.” But Maureen does leave. She goes home to sleep–and dreams of spring, when she’ll be with Pemi and Echo again. And Victoria.

Shows open Memorial Day weekend. 603-745-8913; clarkstradingpost.com

More about bears: Tracking Maine’s Black Bears 10 Bear Facts 1978 Classic: Maine Black Bears

I love Clarks! Been going there for 40 years.