Captain Richard Phillips and the Pirates

AUDIO: Captain Richard Phillips Andrea Phillips Interview The first December snow has come to Underhill, Vermont, and that makes Richard Phillips happy. “My kind of weather,” the 54-year-old Merchant Marine captain says. It’s been only eight months since Somali pirates took him from the helm of the Maersk Alabama, the American container ship they seized […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanThe first December snow has come to Underhill, Vermont, and that makes Richard Phillips happy. “My kind of weather,” the 54-year-old Merchant Marine captain says. It’s been only eight months since Somali pirates took him from the helm of the Maersk Alabama, the American container ship they seized on Wednesday, April 8, 2009, off the East African coast: the first pirate capture of any American ship since the early 1800s.

Demanding ransom, the Somalis held Phillips at gunpoint onboard the ship’s enclosed lifeboat. For the next five days, the story of a ship’s captain sacrificing his safety for his vessel and 19-man crew riveted the world, his face seen across televisions everywhere. Then, on April 12, Easter Sunday, came the electrifying news: U.S. Navy SEAL snipers had killed three of the pirates in one daring, high-risk volley amid roiling seas and fading light. The fourth pirate was in custody aboard a Navy destroyer, where reportedly he’d been negotiating the ransom. “His courage is a model for all Americans,” President Barack Obama said of Phillips.

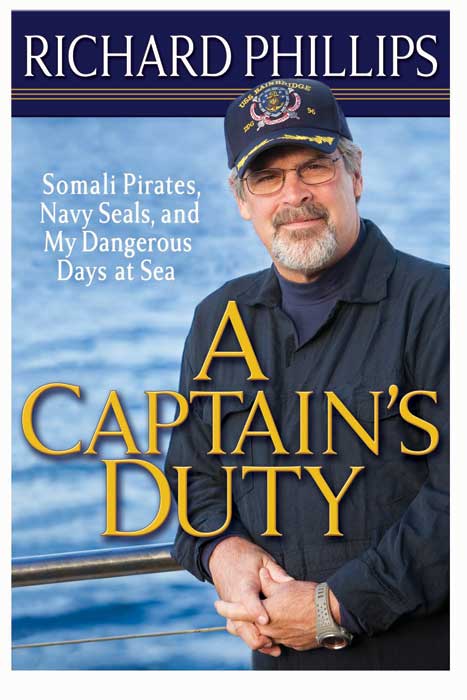

Life for Richard Phillips and his wife, Andrea, an emergency-room nurse in Burlington, hasn’t been the same since his ordeal. After 30 years at sea, 19 as a ship’s captain, he’s been tied to the land since his rescue. He says he wants to head back to sea, but admits that maybe it’s time for new challenges. When his memoir, A Captain’s Duty, is published in April, he’ll be entering his own uncharted waters–a nationwide book tour. Columbia Pictures has bought the movie rights. He meets from time to time with a speech coach, who is helping this natural storyteller hone his delivery, to capture an audience.

Only a day before our visit, however, news reports were focusing on Maersk Alabama crew members who were saying that no matter how heroic Phillips’s actions, he’d been negligent and stubborn in steering his ship too close to pirate-infested waters, even after warnings that a more prudent route would be much farther out to sea. “We all make mistakes,” he says, the snow swirling outside. “I’m prepared for the criticism. I expected it. It’s the society we live in. I think there are a lot of contradictions in what’s being said. Why do things change three, four, six, eight months down the road? I feel comfortable in what I’ve done. I’m sure there’s some human nature involved in this.”

We talk for three hours in Phillips’s rambling 1840s farmhouse, with a barn across the road and 16 acres of snow-covered fields out the windows. He wears a shirt emblazoned with the photo and logo of the USS Bainbridge, the destroyer that rescued him. What follows is an edited version of our conversation. For clarity and brevity, Phillips’s remarks are compressed. My comments in italics are meant as narrative bridges. Phillips’s book, A Captain’s Duty: Somali Pirates, Navy Seals, and My Dangerous Days at Sea, will be published by Hyperion in April.

“Pirates are like a pack of hyenas on the hunt. Usually these are 25- to 30-foot fishing boats [with] high-powered engines on the back. They go fast, and they’re very maneuverable. They’ve got four or five guys in a boat who all live on the mother ship. The mother ship can be a tugboat, a fishing boat, a yacht, [or] just something they’ve stolen. Forty or more guys are living on it, and they either tow their boats or they put them on the deck if it’s a big enough ship, and they go [hundreds of miles] out and they just sit there and drift and wait for a target …

“You have to keep the pirates off the ship. Once they get on, it’s over. I’ve said that before and I say that now. I think ships should be armed [with] specially trained Special Forces types. Give us ways to protect ourselves. Had the mother ship made it to the Maersk Alabama, it would have been over. Then they can put 20 people [onboard] with guns and they can just comb through the ship and find everyone. So it’s imperative [that] the pirates do not get on the ship …

“They were trying to call Somalia, to get the mother ship there, and had they [succeeded], I’d probably still be in Somalia with the whole crew. But they didn’t know how to operate the radar, because I’d disabled it; they were trying to talk on the VHF, but I’d changed channels on them and they didn’t realize it, and they just couldn’t reach the mother ship. They did try and use communications on the sat [satellite] phone, but they didn’t know how to use it properly, and they would even check to make sure I dialed the right number, but I [made sure] it didn’t work. I just told them it was poor coverage on their cell phones …

“[The pirates] were skinny and underfed. The one I called [in my book] Leader was very mean. Said ‘Shut up’ a lot. A good leader, though. Intelligent. Capable. Ran a tight ship. [There were] two tall guys who were very good seamen, I’ll give them that; they knew a lot of knots, very hard knots to tie, let alone untie. [And the fourth] was a crazy young guy [with] Charlie Manson eyes. He had no problem just clicking the gun at me frequently and smiling as he did it …

“Once they got aboard, they were very quick up to the bridge. So me and two of my crew were taken hostage up on the bridge. I knew where [my] men were, because when the pirates were boarding and shooting, they were going from the initial safe room to a backup safe room. [The pirates] wanted me to call everyone else up, but I didn’t give a secret word, so no one paid attention to me. I was also able to cue my mike to let them hear what was going on up on the bridge.

“The pirates went through the rooms a couple of times … and they just couldn’t find anybody. They told us they would shoot us in two minutes unless everybody was up there. And I was prepared for that … But I saw nothing to be gained from my side to give my crew up. Once they get the crew up there, they could just shoot all of us. It’s for the safety of the many against the hazards of the few. And that’s something I knew and accepted … A captain’s duty is to take care of your ship, your crew, and your cargo. Everything derives from this.”

The pirates lost their leader when he was captured by Phillips’s men as he was searching for the ship’s crew. With the crew hidden, the Maersk Alabama shut down by its engineers, and the Somalis’ own high-speed skiff swamped by waves, the three other pirates looked for a way to extricate themselves. Phillips helped them see the advantages of leaving the ship with him. They agreed that they would exchange him for their leader. Once they were all safe in the enclosed lifeboat, however, the pirates said no deal, and Phillips became their hostage.

“I’d been taught that the captain has to be the last one off the ship, but in my situation I knew that the best thing for my ship was for me to get off the ship and take the pirates with me, even though that goes against all the training I’ve ever had … I told the chief engineer, ‘You have the boat ready to go as soon as they’re in the water. Leave me. Don’t worry about it.’ Because my concern at that time was other pirates …

“I told the pirates that they wouldn’t get any ransom for me; I told them we’d [all] die here. And I didn’t expect any ransom to take place, because that’s pretty much the way we are. If you pay the ransom, basically for every dollar you pay, you’ve just enlisted three pirates. I was just their shield, and I saw that they had no qualms about killing me. No qualms at all … I was afraid and fearful for the majority of the time, but I just had to sit that down in the seat next to me and just take care of what’s ahead, and deal with what’s right now, what’s five minutes away, and not worry about tomorrow … You’ve got to hold fast–don’t give in.

“I’ve always had a thing against bullies. People picking on others because they can … Tenacity, I’d guess you could call it. I just wasn’t going to give up. That was my thing, just from playing sports. Even though you’re losing. You ain’t going to give up. You’re still going to fight. And if you lose, you lose. In sports, you get to play again. In this, I wouldn’t. I was going to play the best game I could in this lifeboat. Don’t give up, don’t give in to it, no matter how hopeless. I truly believe nothing is really lost until you’ve given up, and then it’s lost.

“I had a chance to settle my affairs, getting ready to die. I was just saying goodbye to Andrea and [to] Mariah and Danny [his children]. I was just apologizing for the 4 a.m. phone call [saying I was dead] … I was thinking about people who had died: my father, and a neighbor who had died just before I left. I said, ‘I’ll get to see them, and Frannie, my nutcase dog who never came when I called the whole time she was alive.’ And then I would think about my daughter and my son. It still gets to me. I can hear it in my voice. I did pray for strength so that I could know when to try to escape. So that I wouldn’t be too weak when it was time. I always felt there would be a time; that’s what I prayed for, and to give me patience.”

The Navy destroyer Bainbridge moved into position several hundred yards distant early on Thursday. Phillips waited for a chance to escape.

“I’d been on there for over 24 hours. I was in an enclosed lifeboat with no ventilation. The heat was second only to having a gun right in your face or hearing it click behind your head. Because I live in Vermont, the heat was unbearable … They had two guys with AK-47s on me all the time. The forward guy would be sleeping or awake, and the last guy, usually the leader, would be up in the cockpit. I couldn’t wait them out. I had to outwit them. I knew I had to get away before I got to land.

“One of the guys walked forward, and he lay down. Now there were two people snoring up there, and the young guy steps out for a call of nature. I’m mad at myself because I’m a wimp for not escaping yet. I’m not tied up, and I could see [the Navy ship] out the back door. So I got up and pushed him in the water, and I had a chance to go for the gun, but I didn’t know how to use it, so I just dove in. It was just my chance …

“I got probably 50 feet. I popped up and took a look around. The moon was fully out, and it was very light. I said, ‘Oh s—,’ because they’d see my head. I went right back down. I could see them spinning around and yelling, and they were seeing me, and I started doing the crawl toward the Navy ship as fast as I could …”

The pirates moved to where Phillips was swimming. He tried to hide beneath the boat.

“I went back underwater and [the pirates and the lifeboat] are doing circles, and I went from going side to side up and down in the water to listening to footsteps. I was underneath the boat [holding on] by the cooling tubes … I could hear talking, yelling, and arguing, people running around the boat, so when I heard them coming, I’d go to the other side, and I’d hear them come [and] go back to the other side … I was hoping they’d give up. Eventually I popped up, and there was a guy right there, and he took a shot at my head and I said, ‘Okay, okay, you got me.’ They were irate, screaming, swearing. They kicked, hit, slapped, whacked me with the revolver …”

As the hours stretched into days, tensions aboard the lifeboat intensified. The pirates’ leader, sensing impending trouble, arranged to be taken aboard the Bainbridge “to negotiate.” President Obama had authorized the Navy to use whatever force necessary to free Phillips if his life was in imminent danger. On Sunday, April 12, a gunshot rang out in the lifeboat. The Navy saw an AK-47 aimed at the captain’s back. Three concealed Navy SEAL snipers were ready.

“There was animosity building [among the pirates]. Then a shot went off, and the young crazy guy went up to the cockpit, just disgusted, and the other two went up to assure the Navy that everything was all right, no problem. They did something then that they’d never done. And that was the first time, unbeknownst to one another, [that] all of a sudden they were all seen. The military took its chance and gratefully so … I was lucky. I could have died. But I’m alive. So I’m ahead of the game …

“When I came [aboard] the Bainbridge, the men and women on the ship tried to tell me how much of a media maelstrom it was and the eyes that were on it throughout the world, and I couldn’t believe it. Because I can remember just sitting in the lifeboat, saying, ‘I’m in trouble, Rich. I’m in the middle of nowhere with four pirates. I’m in a tough spot. How am I gonna get out of this one? And who knows I’m here?’ So I was just ambushed by [the media attention]. I just couldn’t believe it … It was as surreal being at home as it was on the lifeboat, to be honest. I tell people this, and I really mean it: I think Andrea had it worse with the media than I did with the four pirates. I mean, I knew what I was dealing with.

“I was asked a few days ago, ‘Do you wish it had never happened?’ Two months after the incident, it was ‘Okay, I’m not gonna wish it didn’t happen,’ but now, [eight] months later, yeah, I wish it had never happened. I’d be fine just keeping on the way I was. But you don’t get to make that choice …

“I stopped answering the phone. Because it would just ring from 6 in the morning until 10 o’clock at night. I’m just getting over that. A month and a half into it, [Andrea and I] had this conversation up on our bed: ‘We can just walk away; we don’t have to do anything anyone says. No one tells us what to do.’ Andrea and I got together [and decided], ‘We can’t do everything. Let’s do things we like to do. Let’s do things that can help people. Let’s do things locally.’ … So that was our criterion. And we got to the point that I said, ‘Hey, if we’re feeling this bad about this, let’s just walk away from everything. Let’s just go back to work. No book. No movie. And refuse everything …’

“A SEAL gave me this advice. He said, ‘When you get home for the first month, don’t make a decision … Then take advantage of your opportunities. Pay for your kids’ college. Pay your mortgage. You went through a tough time. Get something out of it.’ … I know it’s a good story. And we don’t have a lot of good stories out there …

“I honestly thought I’d be back to work two weeks after I got off the lifeboat. I really don’t know [my future]. And that’s the most unsettling thing for me, because before, it was just the known, and now it’s a lot of unknowns, and that’s what is different for me. Where will I end up going from here? If it’s back to sea, I have no problem with that.

“One thing people don’t realize. They say, ‘Your life must be great now.’ My life was great before. I was in my comfort zone then. I knew when I was going to work; I knew when I’d be home. And that knowing is where the comfort is. Now I don’t know what’s going to happen … People ask me [whether I’ll] miss going to sea. I say I won’t miss going to sea. I won’t miss a lot of things you have to do to go out there. Because it’s hard work. It’s long hours. But I will miss being at sea. It’s truly an amazing thing to be out there and walk on deck, to be out there with the sunset or moonrise and stars in the sky reflected in the water. Very few people get to see that.”