The Cape Cod National Seashore | The Beach That Saved the Cape

The Cape Cod National Seashore protects miles of dunes, beach, and wild lands in the heart of one of the most popular summer destinations in the country.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

The weathered dune shack appeared like a beacon, rising out of the sand as though it had been waiting for me. Maybe it had. For the past 45 minutes I’d hiked under an intense July sun, through the sandy landscape in a southern section of the Province Lands, a barren, beautiful, 3,000-acre piece of Cape Cod National Seashore in Provincetown, Massachusetts. It had been a meandering journey, slow and uncertain as I traipsed around scrubby trees and wavy patches of dune grass, climbed and scampered down small hills of sand, all in an effort to make it to the sea. Along the way I didn’t see another soul, a welcome solitude.

For two days I’d navigated traffic and tourists: the throngs of fellow visitors on Provincetown’s Commercial Street; the afternoon jam of cars packing Route 6 in Wellfleet; the army of beach seekers at Marconi. “The Cape in summer,” a longtime Eastham resident told me, with the resignation of someone who’d given up hope that the pressure would ever ease. “You just have to learn to deal with it.”

But there was another Cape, he told me—one you could find if you were willing to trek off the touristed path. An empty beach, a quiet forest, an endless expanse of sand and weather-beaten shacks. You just had to look for it.

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

I was. Which is how on a weekday afternoon, I parked at the Snail Road access trail off Route 6 in Provincetown and began walking. I arrived without a plan or a map, venturing along a short path that cut through a thick forest, which eventually led me to the base of a large dune. I galloped up the sand to find a stretch just like it all around me, an expansive brown landscape that seemed like another galaxy away from Provincetown’s crowded center but in reality was only a few miles from the souvenir shops, bars, and restaurants.

“A grand place to be alone and undisturbed,” is how the playwright Eugene O’Neill described the Province Lands in 1919. The area became his muse. He bought a dune shack, hunkered down in the silence, and set out to write Anna Christie and The Hairy Ape, two of his most famous works. Other artists and writers soon followed and never stopped: Harry Kemp, known as the “poet of the dunes”; E.E. Cummings; Jack Kerouac; Mary Oliver; Jackson Pollock; Willem de Kooning; and, perhaps most important, Henry Beston, whose 1928 book, The Outermost House, brought attention to the sheer wild beauty among the sweeping dunes. They squatted on the unwanted sands or slept in the shacks, and mastered the light and the mood. It continues today.

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

The fact that it can is not some lucky accident. On August 7, 1961, President John F. Kennedy formally concluded a debate that had roiled the Cape for nearly 30 years when he signed into law the creation of Cape Cod National Seashore. In the infancy of a development boom that still has not relented, the new park set aside what would become more than 43,600 acres of prime Outer Cape property for public use: beaches and dunes, freshwater ponds and forests, nearly 40 miles in all of untouched Atlantic coastline from Chatham to Provincetown. In an era when the summer vacation became an obsession, in a densely populated part of the country that was starved for public lands, the National Seashore opened nature up to the masses and invited visitors to experience a different kind of seaside: unpolished and undeveloped.

Did the Seashore make the Cape a tourist destination? Hardly. But it did transform it, maybe even saved it, by creating the opportunity for anyone on a beautiful summer day to strike out along a stretch of coastline and feel as though he has an entire chunk of oceanfront to himself.

—

The water has always been the Cape’s calling card. Fishing built towns like Truro and Provincetown, and then, over time, the ocean became more than just something to work. In the mid-19th century, Henry David Thoreau paid four visits to the Cape, traveling by rail to Sandwich, then by stagecoach to Orleans, before hoofing it to Provincetown. Like Eugene O’Neill more than a half-century later, he marveled at its solitude. “A man may stand there and put all of America behind him,” he wrote in Cape Cod, a collection of his pieces published in 1865, three years after his death.

Photo Credit : Courtesy National Park Service

Photo Credit : Courtesy National Park Service

By the late 1800s rail service was bringing wealthy Bostonians to the grand hotels that had sprung up near the Cape’s shores. But it was the automobile that would bring this coastal destination closer to Bostonians and New Yorkers. In 1901, a Centerville businessman named Charles Ayling followed a shoddy network of horse paths to complete the first car trip to Provincetown, and a decade later construction crews laid down the first paved roads. By 1936, a year after the Bourne and Sagamore bridges went up, more than 55,000 cars were crossing onto the Cape on a typical Sunday in summer. From there it wasn’t hard to decipher the Cape’s future trajectory.

“Last summer, as most of us observed, Cape Cod was overrun by hordes of barbarians possessed of a dirty shirt and a two-dollar bill, and a disinclination to change either,” the Cape Cod Beacon, an early proponent of a seaside park, moaned in an editorial at the time.

But the National Park Service, too, had concerns. With the establishment of the big Western parks already behind it, the government had turned its focus to the East and the challenge of creating public lands in a more densely populated area of the country. Beaches became an obvious focus, and when a 1930s Park Service study revealed that only 6 percent of the coast was open to the general public, it moved to identify the areas that stood a chance of being incorporated into a National Seashore. The Outer Cape, located only a day’s drive from nearly a third of the nation’s population, was at the top of the list.

“It had a few things going for it,” says Bill Burke, the National Seashore’s cultural-resources program manager and park historian. “The land was still cheap—estimates were around $10 an acre—and it was still only lightly developed, with a 40-mile stretch of beach from Chatham to Provincetown.”

The very seeds of this conservation effort had been planted in 1928, with the publication of Henry Beston’s book, The Outermost House. A Boston native and frustrated writer, Beston had arrived at a little house he’d built on the sands of Eastham for a two-week vacation in September 1926. But then two weeks turned into a month, and a month into a year. “The beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea possessed and held me that I could not go,” he wrote.

Photo Credit : Henry Beston Society Archives

Photo Credit : Nan Turner Waldron/Henry Beston Society Archives

Stationed in his little house, which he called “Fo’castle,” Beston’s observations of the sea and the land revealed a shifting, delicate landscape, raw and untamed. This careful chronicling of migratory birds and plant life, storms and tides, was in stark contrast to the unnatural world that industrial life embraced, and his work awoke Cape Codders and outsiders alike to a landscape that needed protection. Massachusetts governor Endicott Peabody would later tell Beston, “Your book is one of the reasons that the Cape Cod National Seashore exists today.”

And yet, with the economy still reeling from the Depression and then the onset of World War II, talk of creating a National Seashore was shelved. It would take another two decades, a revamped postwar economy, and a young senator from Massachusetts with Cape ties for the idea to be revived.

Photo Credit : Hy Peskin/Getty Images

In 1955, a first-term Senator Kennedy sponsored a bill that would largely serve as the framework for the Seashore legislation he would later sign as president. Like so many others with long ties to the Cape, Kennedy had seen the coastal retreat he’d grown up with become discovered, built up, more heavily populated. In 1920, the Cape boasted just under 27,000 residents. By 1950 that number had nearly doubled; in another 10 years it would double again. Tourists came, too—hundreds of thousands of them each year. All this new blood wanted what the Cape offered: its rural character, its unfettered access to the sea. But in coming, they changed the very thing they were seeking. They needed houses and hotel rooms, restaurants and shops, bigger roads and bigger amenities. “Land on the Cape is better than the stock market,” one Hyannis real-estate broker gushed. “It’s boomtown all over.”

Farther north, in Provincetown, Boston developer Van Ness Bates had his eye on the Province Lands, which had been under government protection since 1714, when colonial leaders, fearing the deforestation that had already decimated the Outer Cape’s woodlands, restricted tree cutting to keep the sands of its northern tip from blowing into the harbor. Now Ness wanted to pull 1,500 acres into the private sphere in order to execute his big ideas: a heliport, a triple-decker garage, houses, perhaps even a bridge from Provincetown to Plymouth.

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

“You could see the development rolling toward us like a cancer,” recalls Dana Eldridge, a Chatham native whose family lineage goes back to the Cape’s early European settlers. “Dennis, Harwich, these small little towns that didn’t have a chance to support all this development. Marshes were being filled in. People like my parents and myself saw that as a real detriment to the Cape as a whole.”

Eldridge, 82, is a retired teacher; he lives in Eastham in a house that overlooks a small body of water that flows out to the Atlantic. During the first few decades of his life, he witnessed the full arc of the Cape story. In the early 1900s his grandfather, a local storeowner, bought 600 acres of land on Monomoy Island, just off Chatham, for $10 to settle a debt. By the time Eldridge was in his teens, his grandfather wanted nothing to do with the land. “He’d tell me that he’d give it away if he could,” says Eldridge, who has worked as a guide at the Seashore for the past two decades. “He hated paying the taxes on it, as little as they were. Land was useless back then. We knew it was beautiful, but it wasn’t worth anything.”

And then it was.

—

The Marconi parking lot packs an assorted mix of cars: Beamers and Volvos, beat-up pickup trucks and minivans. The scene below, near the water, is much the same: young families and retired couples, single dads and teens, all of them here to be by the sea on a July afternoon. This beach, an unending stretch of sand and water located just a few miles from downtown Wellfleet, isn’t so much crowded as well-attended. Blankets, chairs, and umbrellas press to the water, but there’s real estate in between these carefully selected spots, room to breathe and move around.

And so many of the visitors do. A father throws a football to his young son, while a young couple keep a watchful eye on their toddler. A good 20 feet from them, two teenage boys have recruited their girlfriends to bury them up to their necks. Out in the water families jump the gentle waves that curl toward the others.

It’s a scene that illustrates the Seashore’s democracy. For a $15 vehicle pass or a $45 season ticket, anyone can have access to this pristine beach. Its blue Atlantic. Its long sands. Its commanding 40-foot-high bluffs. This isn’t a gated property, and you don’t need a trust fund to get access to it. It’s there for all of us—which is what its creators had in mind.

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

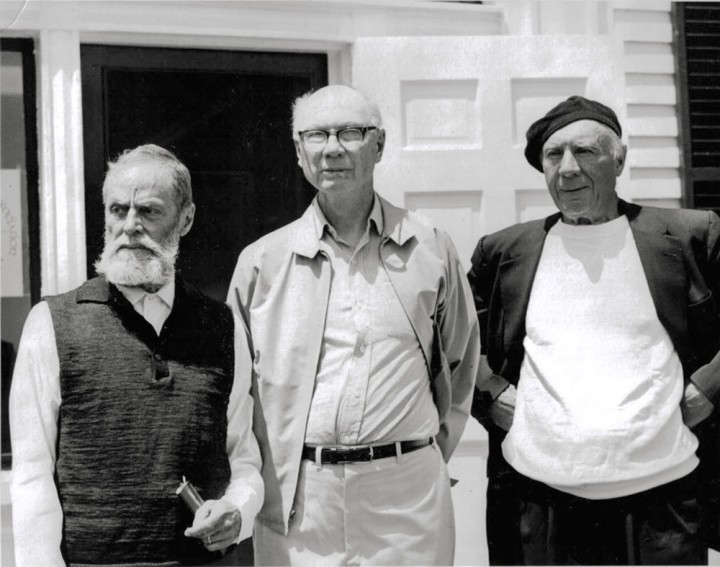

It’s an easy narrative to build the story of the Seashore’s creation around its two most prominent backers: Kennedy and his Massachusetts colleague from across the aisle, Senator Leverett Saltonstall. But that would overlook the groundwork that an army of local believers did to ensure its passage. In Provincetown the fight in the 1950s and ’60s to keep the Province Lands protected and to make it part of the proposed park was led by the painter Ross Moffett and his friend and biographer Josephine Del Deo.

At stake wasn’t just a piece of land but a very way of life. Like O’Neill decades before, the two had found inspiration in the landscape, pulling words and figures out of the barren sands and uninterrupted ocean views. Under Moffett’s leadership, they banded together with other artists and writers to form the Emergency Committee for the Preservation of the Province Lands. There were long nights of meetings and letter writing, phone calls, and general lobbying of fellow residents to secure something that could never again be retrieved if it went under a bulldozer. “We would have lost the Cape, and we would have lost the town,” Del Deo told me.

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

She said this as I sat with her at a long dining table in the Provincetown home she shares with her husband, the painter Salvatore Del Deo. It’s a sprawling house, with big living-room windows that open up to a forest of tall red oaks, and a décor that heavily reflects the couple’s passion for books and art.

The Provincetown that the Del Deos discovered when they first moved here in the early 1950s was one that was in the last throes of its old maritime identity. Fishing boats still stocked the harbor, while in town five cold-storage plants ran without rest. Intermixed with this hard-working community was a thriving artistic community that was captivated by the light and the water. The Del Deos became part of that population, and in between childrearing and community work, spent as much time as they could in a little dune shack they rented from a family friend. More than 50 years on, that little building is still a part of their life.

“As a writer there isn’t anything that equals solitude, and as a painter the landscape is so gorgeous, how could you do better?” said Josephine, who had recently completed The Watch at Peaked Hill, a memoir about her life and work in the Province Lands. “We’d go out there and feel this liberation from our civic responsibilities—having to answer the telephone, having to attend meetings. We could just go out and create. We didn’t have to worry about people bothering us, and for artists that’s a very big thing. The chance to do nothing but think about their art.”

Josephine, who’s short, with big green eyes and a preference for punctuating her words with her hands, still speaks with the kind of force and precision she used to push for passage of the park nearly six decades ago. At times, she slapped the table to hammer home her point.

Photo Credit : Yankee Publishing Collection/Historic New England (Hawthorne Art School, Provincetown, 1929)

“A lot of people hated the idea of the park because they knew goddamned well it would stop development,” she said. “And you had these developers come in and tell us that we really had to turn over a part of the Province Lands because there wasn’t enough room for the town to grow. ‘You have all this space,’ they said. ‘You should build out there.’ Baloney. Who was going to benefit? The developers. The little guy on Brown Street wasn’t going to even smell that land.”

Down Cape it was much the same, as business owners warned of an economic Armageddon if the park went through, while conservative selectmen railed against the idea of turning even a single grain of sand over to the federal government. “Local feeling ran so strong against the plan,” the late Speaker of the House Thomas “Tip” O’Neill once recalled, “that [Congressman] Eddie [Boland] and I were booed out of Town Hall in Eastham and were hung in effigy in Truro.”

But Del Deo, Moffett, and others pushed on. At the Provincetown Town Meeting on March 13, 1961, voters came down on the side of handing over the Province Lands to the proposed park, 144 to 61. Four months later, President Kennedy used 27 different pens to sign the Seashore legislation and turn it into law.

Photo Credit : George Yater/Provincetown Art Association and Museum Archives (Moffett)

As for Del Deo, a look of relief came over her face as she recounted the victory, as though she were experiencing the outcome for the first time. “When the Seashore went through, we were all so overjoyed,” Del Deo told me. “None more so than Ross. This wonderful man had sacrificed a great deal to do this.” She paused, then closed her eyes for a brief moment as she remembered her old friend.

“He was this great American painter, at the end of his life, who poured a few important years of his life into protecting this place. There were many heroes in this fight, but Ross Moffett made a major contribution.”

—

More than 50 years after it was created, the legacy of the Seashore is still being written. That’s because the strength of the park is that it is many things. It’s an expansive beach. It’s an empty plain of sand. It’s a bike path. It’s a trek through an oceanside forest. It’s a lighthouse tour. It’s an old military site. It has preserved the Outer Cape without locking it away. In fact, it has done quite the opposite: It has ensured the Cape’s survival by keeping its doors open and providing an up-close opportunity for visitors to find the same kind of beauty and wonder that first attracted Thoreau, O’Neill, and Beston.

Along the way it has transformed the Cape’s economy, but not in the manner its early opponents expected. In the summer of 1964, the second full season the Seashore was open, hundreds of thousands of visitors streamed through it each month. Today, it’s among the top 10 most visited national parks, with more than 4.5 million people trekking through it every year. It has filled restaurants and motels, crowded downtowns and roadways—adding nearly $187 million each year—all without destroying the untamed beauty that defines the Outer Cape.

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

Photo Credit : Christopher Churchill

That was more than apparent as I slowly moved closer to that Province Lands shack that I’d fixed my eyes on. A full afternoon sun was right on top of me as I worked along a rough trail, a flat stretch of sand that eventually crossed a narrow dune-buggy road. I scampered up a small hill and there it was, nestled into the earth as though it had fully accepted its fate: that one day it would be consumed by the sands. A mix of vegetation—small shrubs and unwieldy patches of dune grass—framed the building, whose weathered door and beaten cedar shingles gave it an inviting appearance. A rusted lock kept the old door shut.

A good 20 yards in front of the shack were a table and two chairs, positioned perfectly to take in the view before it: a wide strip of sand and a softly rolling Atlantic. Not a single other person was in sight. I took a seat and settled into this moment, when it felt as though I had one of New England’s prized summer destinations all to myself.

It was the Cape in summer.

Editors’ note: Walkers and hikers who use the Province Lands should stay on established paths to avoid causing erosion. The National Park Service also suggests that visitors keep a respectful distance from the dune shacks so as not to disturb the occupants.

Loved this article. Thanks for the great history lesson on such a special (shared) part of New England!

My family has been in trouble for over 200 years this is where my heart sings

Lovely article but needs corrections. If the author would like to talk I encourage a conversation. Please get in touch. Peter