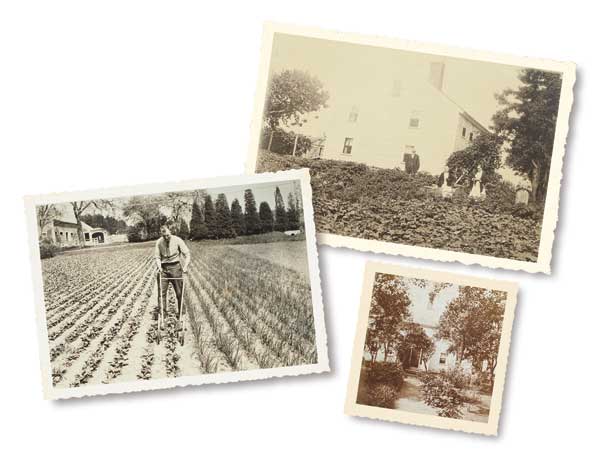

Lucy Tuttle sits on a patch of grass facing the empty storefront where she has sold her family’s produce for the last 35 years. She leans back, pressing her palms into soft grass still wet with dew. It is an unusually warm spring morning in Dover, New Hampshire. The air smells fresh, a combination of flowers and dirt. This is the smell of her childhood, the smell of the sowing season. Because she was a girl, she was never expected to help spread manure or plant seeds in her youth. Her brother did that. Instead, she and her little sister, Becky, roamed the farm’s 245 acres, paddling rafts along the irrigation canals, spying on the teenage boys their father hired as farmhands. Now there are no farmhands. The fields behind her lie fallow. The store before her is dark and empty.

The sign by the road still bears the store’s name in bold letters:

Tuttle’s Red Barn. But the marquee that once advertised the day’s selection of crops is blank. Dandelions have sprouted in the gravel around it. Lucy can see the red paint starting to peel in patches from the storefront. Empty produce baskets are lined up by the front door, as if waiting to be allowed in. A white plaque by the door still reads:

Welcome to Tuttle’s / America’s Oldest Family Farm / Est. 1632.

This is the first spring of Lucy’s lifetime that the fields haven’t been planted with corn and cucumbers, strawberries and squash, pumpkins and peppers. In fact, it’s the first time in nearly 400 years that this land hasn’t been planted by a Tuttle: her brother, Will; her father, Hugh; or any of the nine generations of farmers who came before him. Lucy’s forefather, John Tuttle, made his way to what today is the seacoast town of Dover–one of New Hampshire’s oldest permanent settlements–in 1635 with a 20-acre land grant, secured three years before from King Charles I of England, and broke ground in the middle of a point of land between two tidal rivers, the Bellamy and the Cocheco.

Now the farm is up for sale. At first, Lucy resisted the decision to sell, which was her brother’s. “Over my dead body,” she told him. As recently as five years ago, Lucy believed that the farm would live on in Tuttle hands. She still expected some member of the 12th generation–her son, one of Will’s four children, or one of Becky’s three–to come back and take the reins. Failing that, she secretly believed, well into her sixties, that she and her siblings could simply go on farming forever.

Seated on a patch of grass that is still–for now–Tuttle soil, Lucy looks around at a landscape so familiar that she almost can’t bring it into focus anymore. It’s like looking at herself in the mirror: She doesn’t notice the details, just an overall impression of a part of herself, staring back. She thinks about what it would mean to no longer claim this land as her own.

She tucks her left leg beneath her, stork-like. Her knee still accommodates these origami folds; it’s just a little creakier than it once was. At 67, she’s the eldest of the 11th generation of Tuttles. She feels like the youngest. Will has been as stubborn as an old man for decades. When Lucy wanted to breathe new life into the struggling farm, Will resisted. Why not let people pick their own strawberries or pumpkins? Let them interact with the land? Will didn’t want strangers tromping around the fields. Why not play up the farm’s deep history–offer hayrides and tell tales about the early days on the Tuttle Farm? No, Will said: no hayrides. The conversation ended there.

A red-tailed hawk soars overhead. Lucy reaches up a hand to shade her eyes and watches it circle. She doesn’t argue with her brother about the farm anymore. After all, Will owns the land and two-thirds of the business. The decision to sell, she recognized, was his to make–just as the decisions about strawberries and hayrides were his to make. Where she once chafed, she now acquiesces.

Two years ago, she finally told Will, “Well, okay, we can sell the farm. But it can only be to the most fabulous person, with the greatest ideas in the world.” So they met with planners and developers. They entertained a proposal by a nonprofit group that would have used the land for agricultural education, training would-be farmers–but the arrangement faltered after one season. In the meantime, Lucy thought deeply about this most treasured of Tuttle heirlooms.

The gem of her family’s farming legacy, she realizes now, has also been a burden. It has divided the three siblings of the 11th generation: the two girls, who wanted to take over the farm but were denied it by patrilineal order, and Will, who early on wanted it least but has borne its yoke. New Hampshire farming, as Lucy knows, is not for the fainthearted. The U.S. Department of Agriculture charitably describes the state’s soil as “relatively infertile.” New Hampshire ranks third to last nationally in the worth of its agricultural exports.

The Tuttle family is one of the few to have consistently plucked a livelihood from that stony soil. In the centuries since Charles I doled out land grants to New Hampshire’s first wave of farmers, all but the Tuttles at some point gave up on the land, and on the grueling 18-hour workdays, to pursue other lines of work. The Tuttles held out for almost 380 years.

But at what cost? Lucy wonders. Is the farm’s longevity testimony of her family’s disposition for farming, or of their sense of duty? Is the Tuttle legacy one of love for the land, or of stoic obligation to tradition? And what would it have taken to keep it going?

—

Lucy’s house sits just up the street from the red barn, overlooking the eastern fields. Will lives in the old farmhouse, where their grandparents lived when he and Lucy were young. Out back, a barn houses old tractors–some of the same ones from Lucy’s childhood, still in working condition.

She smiles when she replays some of her memories of the farm: lively family dinners, the antics of colorful farmhands, the night Will slept outside after being sprayed by a skunk he was trying to catch. Lucy grew up among three generations of Tuttles: her grandparents, her parents, and her siblings, Will and Becky. When the family sat down at night around a heavy wooden dinner table, her grandfather would boast that everything on the table except the salt had come from their fields. “And the rum,” someone would add–although the family did make their own hard cider from the apples her grandfather grew.

She smiles, too, when she speaks of her father. He was, she says, the consummate farmer. In the late 1950s, as an experiment, he cleared an acre of wooded land, just to see what it must have been like for the earliest Tuttles. He chopped the pine trees and cleared tractorloads of rocks. The soil was so acidic, so steeped in pine needles, that it took seven years for anything to grow. And the field was so remote it couldn’t be reached by irrigation. Some years the raccoons ate everything before the crops were ready. But that wasn’t the point: The point was that Hugh Tuttle could do what John Tuttle had done. Lucy knew that her father thought often, in the fields, about his ancestors. He felt connected to them through farming.

That sense of connection to her ancestors pulsed in Lucy’s veins, too, but she couldn’t be a leader on the farm: couldn’t clear an acre as an experiment; couldn’t plant an orchard or chop it down. As a teenager, she could only work in the store with her mother and a half-dozen other teenage girls, hired in the summer months to help serve as many as 1,000 customers a day. She could only look out the window at a nearby field, where teenage boys weeded the rows of carrots.

Lucy felt little passion for working the cash register. So in her early twenties, she left home in 1967 to pursue a life of the intellect in Europe; seeking high culture in Paris, she arrived just in time for the student riots of 1968. She stayed six years, teaching English.

While Lucy was gone, a reporter from

Life magazine visited Dover to write a story about what appeared to be the imminent demise of the family’s farming legacy. Lucy read the article on the banks of the Seine, not the Bellamy. Tuttle Farm, the article proclaimed, would die with Hugh Tuttle. He had hoped that his only son, Will, would take it over. But Will, then 24 and a graduate of Tufts University, was working instead for Campbell’s Soup as a sales representative.

“People say to me, ‘How can you not take over? Think of all the tradition you’re letting go!'” Will was quoted as saying. “But you really have to love it to undertake anything like that. By the end of March my father starts cussing about how the snow isn’t melting fast enough. He just loves farming. The fact is, I just don’t get a kick out of seeing something grow.”

Lucy knew that her father had no expectation that either of his daughters would carry on the family’s farming legacy. Without Will at the helm, he didn’t expect the farm to go on, although Becky–19 at the time of the article–had begged him for the chance to try her hand. She was the true farmer of the family, the one with the green thumb and a deep love for the land. But Hugh wouldn’t hear of it. Later, when she married and moved away, cutting ties with her parents and siblings, making almost no contact for years, Hugh felt vindicated. Women, he reiterated, become wives, not farmers. But Lucy suspects that if he had let Becky farm, she wouldn’t have turned her back on the land or the family.

In Paris, when Lucy read the magazine, she felt the tug of her own roots, pulling her back to the farm. So in 1974, she came home–with manicured nails, speaking French-inflected English. Again, she helped her mother run the farm stand. Occasionally, she received letters from her European friends in glamorous, translucent blue air-mail envelopes. Her parents eyed them skeptically.

Lucy threw herself into farming, hoping to impress her father with her zeal. She married one of those farmhands she’d once spied on in the fields. She attended plant-science classes at the University of New Hampshire and shared the latest advances in farming technology with her father. She came up with new ideas, ways to carry the Tuttle farm into the future. But nothing in farming was new to Hugh Tuttle.

“I tried that 20 years ago, and it didn’t work worth a damn,” he’d say. So she confined her ambitions to running the store.

—

Will had come home in 1972–swayed, in part, by his father’s searing quote, printed in

Life for the world to see: “It’s kind of tough when you turn out one son and you hang all your hopes on him and they don’t materialize.” By the time

Yankee published its profile of the Tuttle Farm in 1981, Hugh seemed aware of the burden he’d placed on his son but not aware that there might have been other options: say, hanging some of his hopes on his daughters. He explained to the reporter that it was the family tradition to pass the farm down to the youngest son in each generation. “We were in a difficult position as parents,” Hugh said, matter-of-factly. “We tried three times and got only one boy.”

It seemed only natural to Hugh for Will to take charge, but he wasn’t ignorant of the weight of his hopes on Will’s shoulders: “This poor kid, from the time he was 5 all his aunties and grandparents would say, ‘Well, Willy, I suppose you’re going to be the farmer in the next generation.’ And the poor kid hated every minute of it. And I didn’t handle it well. I expected too much of him as the only son. I wanted him to love the place so much that I drove him away.”

Will, who suffers from hay fever, was literally allergic to his father’s lifestyle. Lucy still remembers one summer, in their teens, when Will purposely gashed his hand with glass to get out of weeding the radishes. But in 1981 Will told

Yankee that returning had been the right decision. “I feel so strongly about the place now,” he said, “that I have a hard time believing I didn’t want to do this.” He also revealed a more modern vision for the farm’s future: one that didn’t depend exclusively on the youngest son. “I don’t stick my thumb in the soil every day and say it’s mine, and in 30 years it’ll be my son’s,” he told the reporter. “I like to think I’ll hold as much hope for my daughter as for my son.” Lucy noticed, however, that he didn’t mention his sisters.

Will’s labor freed up his father to spend more time with the family he’d left behind in the days when he’d spent 18 hours a day working the fields. When Lucy’s son, Evan, turned 3 in 1981, Hugh stayed long after the birthday guests had left, building a model garage for Evan’s growing collection of toy cars and trucks. Lucy sat on the rug and watched them. She felt a sudden surge of longing for the connection she hadn’t forged with her father in her youth–while, through farming, he’d bonded instead with the Tuttles of the past.

“My father is a wonderful grandfather,” she told

Yankee. “I have very few memories of him when I was a child, because he was always in the fields, but he’ll take Evan for rides on the tractor. Every night in summer I have to take Evan down to the farm so he can sit on all three tractors and grip the steering wheels.”

But this thought brought another stinging realization: Evan, who has his own father’s last name, Hourihan, wouldn’t have a future on the farm, according to the current rules of inheritance. He wasn’t a Tuttle; he had no claim to the family legacy.

“It’s a Tuttle farm, and that’s the way it’s been,” Lucy explained. “He would always be in a sense a second-class citizen. He’s not the son of a son.”

She thought again about the value of the legacy, and why the family farm would come with such strict rules of inheritance. Perhaps, she thought, that strictness could be the reason the farm had prospered as long as it had. “Maybe the Tuttles knew all along,” she said, “that the only way this farm could survive was to keep it from being dispersed.”

—

It’s the fall of 2011, a drizzly September afternoon, just a little more than a month before the farm stand will close for good. Lucy stands behind an antique desk under a plastic awning outside Tuttle’s Red Barn. The store itself closed in August. Lucy is selling the produce of the farm’s final season on the outside patio. It’s a pared-down return to an earlier version of the Tuttle farm stand, before the Red Barn went up, with its refrigerated cases and six checkout lanes.

A few regulars sort through bins of peppers and beans, tomatoes and corn. Will is in the process of hauling 2,000 pumpkins from the field to the farm stand. Here where the field meets asphalt, at the edge of the farm stand’s parking lot, the pumpkins form a blazing orange border against gray skies.

This season hasn’t been kind to the pumpkins–“too wet,” Will says, when he stops in at the farm stand with a load from the fields–and they’re smaller than normal, slightly lumpy. One by one, Will lifts the gourds, slick from rain, off the flatbed behind his blue tractor and sets them down in the wet grass. It’s cool this afternoon, but he works in shorts and a T-shirt. A baseball cap keeps the rain off his ruddy face. At 64, his hair and beard have grown white, but he still handles his share of the farm work. Lucy and Becky share the work of manning the stand.

Today Lucy is working the register alone. She is, in large part, the face of the farm. She seems as much a part of this landscape as the pumpkins. She banters easily with the customers, who all know her well.

Two elderly women with short, permed hair are rifling through a basket of corn. “I have some corn already husked, and it’s the same price,” Lucy tells them, emerging from her spot behind the wooden desk. Even behind a desk, she can never sit still. “The others are wormy at the tip; they haven’t been sprayed. You’ll have to cut the tips off.”

This is the first season in Lucy’s lifetime–and the last, as it turns out–that the Tuttle crops have been raised without pesticides. She’s excited about the change, even though it means waging a war on worms among the cornstalks. This is one change she herself has instigated: She convinced Will to work with a nonprofit farming group this season, letting a few young farmhands grow organic crops and share the profits with the Tuttles. It’s the kind of revolutionary approach to farming of which Lucy would have wanted to do more, if the farm had been in her hands.

The women amble over to the beans. One spots a display of purple string beans–a new and exotic addition to the farm’s inventory for this final season. “Oh, for heaven’s sake!” she says.

“When you cook it, the purple goes away,” Lucy explains. “It’s heat-sensitive.” The women choose the green beans instead, and the prehusked corn. They ask Lucy if the farm has found a buyer yet. “We have a lot of suitors, but no ring,” Lucy says. She’s been repeating the line a lot lately.

The decision to sell hasn’t been popular with Lucy’s neighbors and customers. The Tuttle Farm is a focal point in Dover, where Hugh Tuttle was once mayor. It’s an emblem of the community’s agrarian roots that it’s also geographically central: It lies just southeast of the center of town, past a row of car dealerships and the cemetery.

Being the oldest farm in America puts this place in the spotlight, the glare and heat of which most farmers will never feel. If the Tuttles had decided to sell out and become blacksmiths in the 1800s, Lucy points out, no one would have batted an eye. But wait two more centuries to get out, and suddenly everyone who’s ever bought a tomato is urging you to keep farming: “They say, ‘You can’t do that! You’re a historic place. You’re not allowed!’

“Well, of course we can do it. It’s our farm; it’s our bodies. So I’ve suggested to the people who most adamantly say, ‘But you can’t, you can’t’: ‘Well, okay,

you do it.’ ‘Oh no, I couldn’t do it.’ Well, I can’t do it either. We’re too old. We can still bend over and pick things; we just can’t get up again.”

Lucy wonders what the farm would look like today if she or Becky had been given the chance to run it. She doubts they’d be waiting for a suitor to make good on an offer. Neither of them would want to part with the farm, despite the hard work and minimal profits. There are ways to make the farm more successful, Lucy thinks: tapping into the local and organic food movement, for example. With enough dedicated farmhands, they could take it in a new direction. But it’s too late for that now.

—

On this April morning, it’s been more than a year since the family put the farm up for sale; they shuttered the store in October. The original asking price was $3.35 million for the proptery’s remaining 134 acres (which are under a conservation easement) and the farmhouse; it’s now $1.875 million, excluding the house. There’s been a lot of interest, including a few tentative offers to purchase the land where Lucy is sitting, absentmindedly plucking clumps of clover from the grass: “Many suitors, no ring, still being courted,” Lucy quips. A breeze ripples her short, strawberry-blonde hair, making the tendrils wave like wheat.

Today, as she surveys the land, she allows herself a hard-won sense of peace. She takes in the gentle slope of the fields, cascading down from the east to the road that bisects them–once part of New Hampshire’s main north-south throughway–then jumping the asphalt to continue their rolling descent west before ending in a border of tall pines. Whenever she returns from a trip, whether as far away as Paris or as close as the hardware store, her heart jumps a little at the crest in the road where the fields come into view. “I’m home!” she always thinks. But today she tries to picture this as a place. A farm. A business. Not a home. “Sell this goddamn place!” she lets herself think. “If I don’t like who buys it, I can move away.”

Saying goodbye to the farm has been a long, painful process. Lucy’s son Evan was among those tortured by the decision. In the end, Hugh didn’t mind that Evan had a different last name; he hoped to hand his legacy livelihood over to his grandson. And Evan, 24 years old and wracked with grief as 81-year-old Hugh lay dying in the farmhouse 10 years ago, promised that he would carry the business end of the farm for another generation. Now Evan works a desk job in Chicago while he pursues his true passion–creative writing–in his free time. His heart wasn’t in farming. Lucy didn’t push; it was more important to her that Evan find fulfillment than that he keep up the family tradition out of sheer obligation. In the end, she thinks, the farm is just a farm.

“People ask me, ‘Don’t you just want to die? Isn’t this the saddest thing that’s ever happened to your family?'” Lucy says. “Well, no, it’s not.”

She’s starting to recognize that the farm isn’t the only thing that connects her to her roots. Parting with the land of her ancestors has brought the living members of her family closer together. Becky, now divorced, has moved in with Lucy. And both now work for their cousin, Dave Tuttle, who runs his own farm just over the Maine state line. In Dave’s greenhouse, where she and Becky transplant seedlings, they still carry Tuttle soil beneath their fingernails.

As Lucy leans back into the grass, propping herself up on her elbows, a form appears at the edge of the field behind her. It’s a girl–one of Will’s daughters–jogging in the rutted dirt where there once grew rows of sunflowers. Her strawberry-blonde ponytail bounces with each step. Lucy turns her head and raises her hand to wave. “Nice form, Daisy!” she calls. The girl disappears behind the treeline.

For details of the sale, contact Robert E. Gregg Jr., Concord, NH; 603-227-2413; rgregg@landvest.com; tuttlefarm.landvest.com

I simply wanted to make a brief comment to be able to express gratitude to you for these pleasant ways you are giving out here. My considerable internet investigation has now been compensated with extremely good points to write about with my family. I ‘d point out that most of us site visitors are unquestionably fortunate to exist in a wonderful network with many wonderful individuals with valuable tips and hints. I feel pretty lucky to have seen your entire webpage and look forward to many more brilliant moments reading here. Thanks once again for everything.