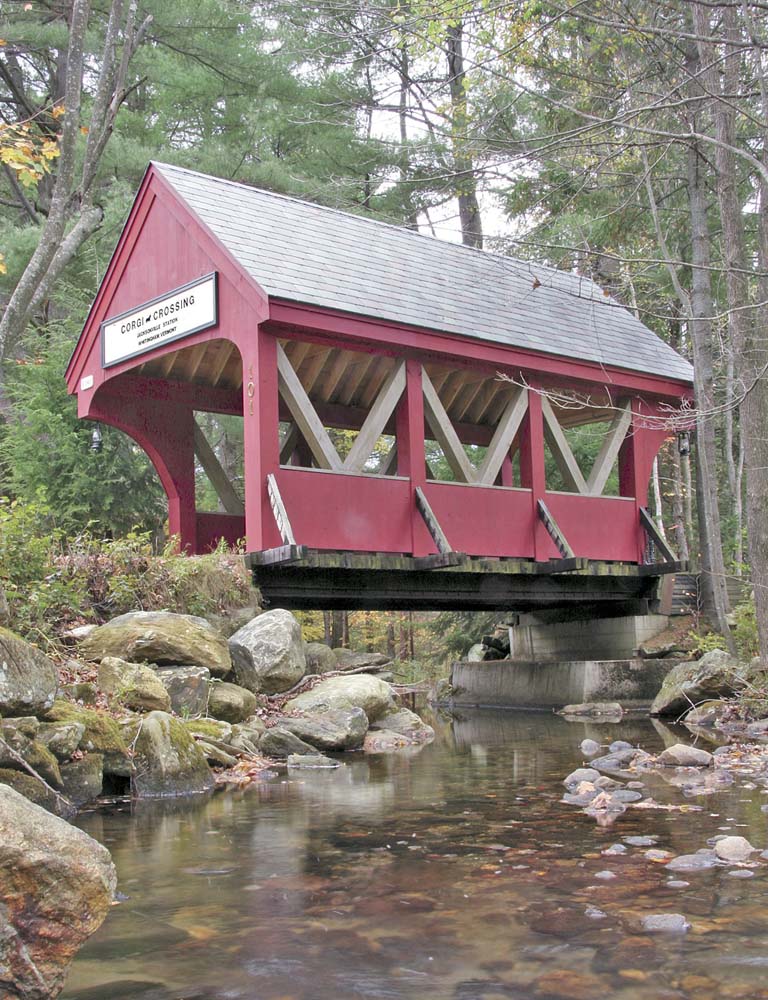

Covered Bridge Driveway

The lone covered bridge in Whitingham, Vermont, is on Ed and Diane Takorian’s hillside property. With gable ends, Douglas fir decking, wrought-iron lanterns, and a too-real-to-believe artificial slate roof made of recycled tires, this 26-foot span is small but stunning. The Takorians could have built any old bridge — but Ed, a retired tool machinist […]

The lone covered bridge in Whitingham, Vermont, is on Ed and Diane Takorian’s hillside property. With gable ends, Douglas fir decking, wrought-iron lanterns, and a too-real-to-believe artificial slate roof made of recycled tires, this 26-foot span is small but stunning.

The Takorians could have built any old bridge — but Ed, a retired tool machinist and a gifted carpenter, hardly has a fondness for the mundane. He built the couple’s home, barn, sugar shack, and teahouse — he likes a good challenge.

“When we bought the land, we asked the town whether it would build us a bridge so that we could build our house,” he says. “They said we’d have to do it.” Ed shrugs: “Which was fine.”

PROCESS:

Construction of the bridge, which crosses Big Rock Brook, actually came about in two parts. First, in 1984, soon after the Takorians bought the land and set out to build their dream home, they needed a structure that could support heavy construction equipment.

The resulting bridge, which Ed designed and built, featured four steel I-beams, two cement abutments, and for the decking and railing more than 100 recycled 3×6-inch Douglas fir planks.

To create the decking, he laid the planks on end and connected them with a series of 9-inch pole barn nails. And there the bridge stood for 21 years, serviceable (it can support 50 tons) but unfinished. “We couldn’t afford to put a cover on it,” says Diane.

Then, two years ago, the Takorians completed what they’d started. For the supporting roof structure, they went with a king post design and turned to a local sawmill for 20 7×7-inch hemlock beams, which Ed attached with pole barn nails. The basic roof construction was of spruce: 2x10s for the rafters, with 2x8s for the collar ties, spaced 32 inches apart.

Wanting an “older” look, Ed used 1-inch-thick rough-cut pine of varying lengths and widths for the sheathing. “I didn’t want to see plywood,” he says. Not wanting to look at exposed shingle nails and splitting wood, either, he used 1-inch screws: enough bite to tack down the faux slate shingles without going all the way through the boards.

Design and functionality also merged at the gable ends. For aesthetic reasons, Ed didn’t want to make the two portals any higher than 8 feet, but the fire department said the structure would have to accommodate emergency vehicles. The solution lay in extending the height by 3 feet, with doors on the ends that open and close via a simple pulley system. Locks are four small maple slabs, with furniture knobs you turn via a long hooked pole. “Everything’s a little improvised around here,” Ed jokes.

The arches, too, with flexible quarter-inch lauan plywood forming the outside curves, are more than just design elements. They offset the bridge’s slightly diagonal position by extending their respective ends 4-1/2 feet and squaring the roofline. For siding, Ed chose 1×10-inch shiplap pine — “when it shrinks, you don’t get those spaces between the boards” — and coated it with barn-red acrylic latex.

Other touches include a small pull-down bench, electric timers for the lanterns, and a wireless motion detector to hustle the couple’s two Corgis off the driveway whenever a car approaches.

COST:

Total price for materials was $7,200, including $6,000 for the covered section of the bridge.WHAT DO YOU LIKE MOST?

“We love Vermont, and we’ve photographed every covered bridge in the state,” says Diane. “There isn’t one like it. It’s totally unique.”RESOURCES:

Cabot Stains, Newburyport, MA. 800-877-8246; cabotstain.comStone’s Sawmill, Jacksonville, VT. 802-368-2498

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich